By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Arenamedia Pty Ltd. and IFC Films.

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Arenamedia Pty Ltd. and IFC Films.

Making the most of the global shutdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Australian filmmaker Adam Elliot mapped out what would become an Oscar-nominee favorite for Best Animated Feature and an Annecy winner. Memoir of a Snail tells the tale of Grace, a hoarder of snail memorabilia who longs to be reunited with her twin brother Gilbert while experiencing the trials and tribulations of becoming an adult. Previously, Elliot made his feature film directorial debut in 2009 with Mary and Max, but interestingly, the methodology and technology between the two productions have not altered much.

“The technology has changed,” states Adam Elliot, Producer, Director, Production Designer and Writer. “Dragonframe is a wonderful tool. The animators love it because they can do all sorts of tricks, and it’s got all sorts of bells and whistles. I apply many restrictions on my animators and try to get them not to rely on the software too much, animate from intuition and celebrate happy accidents. We have LED lights now, so the stages aren’t as hot. The globes don’t burn out as quickly. Sound editing and design are far more digitized. The sound libraries are bigger. Cameras have gotten higher megapixels, so the resolution is much higher. Having said all that, they’re just tools. We still try to animate in a traditional manner. Everything in front of the camera is done traditionally. We don’t do any CGI additions. However, we certainly do cleanup digitally, like removing rigs. All our special effects, like fire, rain and water, are all handmade. The fire is yellow cellophane. We celebrate the old, but we certainly embrace the new.”

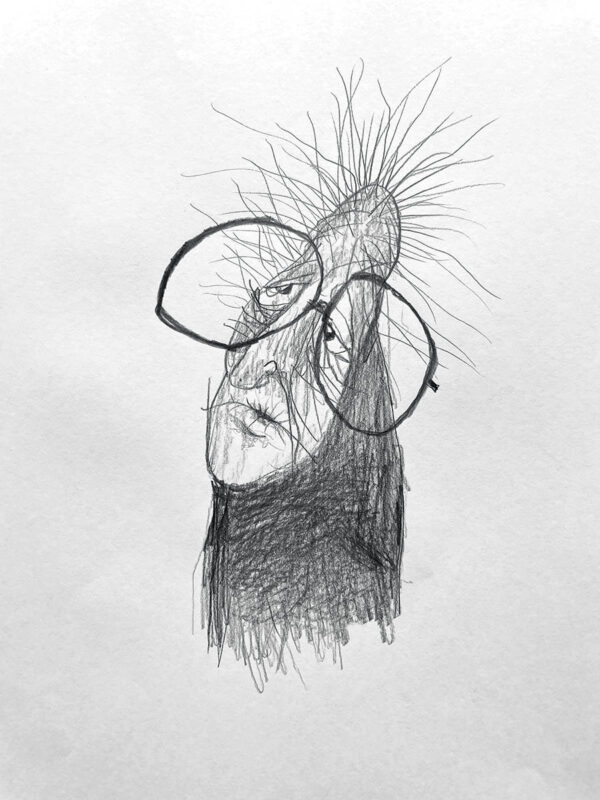

“We can say to the audience that you can hold in your hand every prop and character you have just seen. However, there was a lot of post-production to make it look that way! There were roughly 1,500 storyboard panels. Then I drew and designed all of the characters [200], most of the props [5,000 to 7,000] and sets [200]. I drew by hand because I was in lockdown during COVID-19 and had a lot of time!”

—Adam Elliot, Producer, Director, Production Designer and Writer

Visual effects have come a long way, allowing for more creative freedom. In the old days, we would use fishing line to have things airborne, and now we can have a big metal rod and the visual effects artists remove that digitally,” Elliot notes. “That’s about it. It’s just cleanup. There is a lot of compositing. For elements like fire, we do it on a piece of glass with the camera looking down, often with a greenscreen background, then we composite that in post. We had 600 visual effects shots in the film, and a lot of money spent on the visual effects, but it was mostly basic stuff.” One of the more complex effects was the burning church. “Those flames are recycled and layered,” Elliot explains. “We do one set of flames, then cut, paste and layer them. The claim is that we can say to the audience that you can hold in your hand every prop and character you have just seen. However, there was a lot of post-production to make it look that way!” Every shot was storyboarded. “There were roughly 1,500 storyboard panels. Then I drew and designed all of the characters [200], most of the props [5,000 to 7,000] and sets [200]. I drew by hand because I was in lockdown during COVID-19 and had a lot of time!”

Compositing was only used where necessary. “Most of the skies you see in the film were on set on giant canvases,” Elliot remarks. “There were only one or two skies or maybe more where we did greenscreen then composited in one of the canvas skies. It is a wonderful tool that now liberates us as stop-motion animators. When I left film school in 1996, I was told I was pursuing a dying art form and that stop motion would be obliterated by CGI. The complete opposite has happened. CGI and digital tools have liberated us. You have to be careful not to get carried away. There is a hybrid look that has gone a bit far, and now with 3D printers, too. Some of these stop-motion films almost look computer-animated because they’re so slick. We’re trying to celebrate the lumps and bumps, brushstrokes, and fingerprints on the clay.”

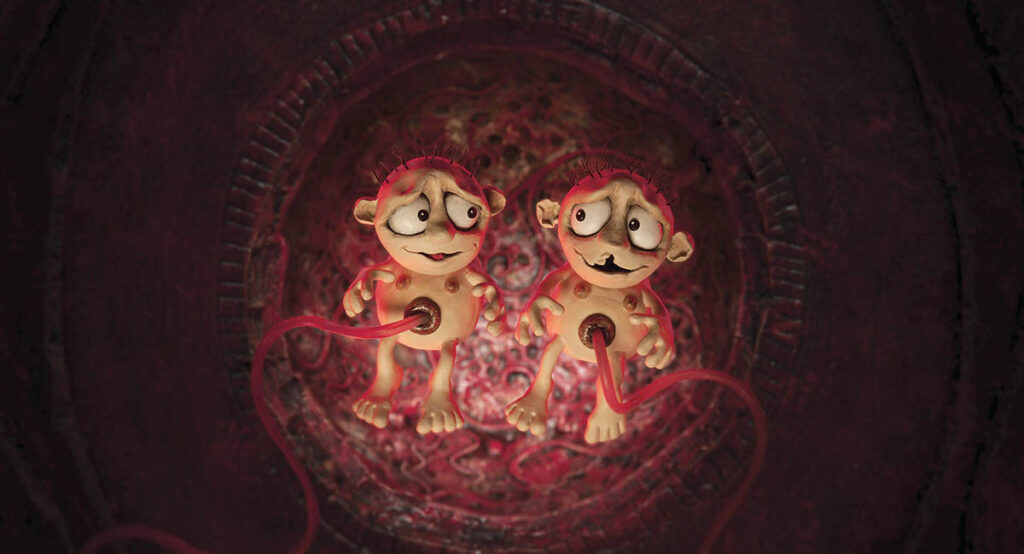

The design of the characters was based on what Elliot was able to accomplish in his one-room apartment. “Adam started making everything out of Apoxie Sculpt, which is this material that sculpts like clay, then goes rock-hard in about an hour,” explains Animation Supervisor John Lewis. “We had stylized the characters around the fact that they were solid and budgeted around it as well. Creating a character’s costume out of real fabric or silicone that can bend is time-consuming and expensive. Adam wanted us to have these rock-hard-solid puppets. They’re like statues; in some sense, that’s easy because it restricts what the puppet can do. Sometimes, when you don’t move the head, the ear clunks into the shoulder, and you can’t move it where you want it to move, or body movements are stiffer or different than how you might move it otherwise. Adam wrote ‘walking’ out of the film as a stylistic and budgetary choice. If we did have characters walking full frame where you can see their feet, we would have had to have legs that could bend and pants. Instead, we cropped it with the camera, removed the legs and put a little up-and-down rig underneath, which was a cheap microscope stand. It’s about the same size as the puppet’s legs. We put that on the table and slide the character along; that’s how we get dynamic movement.”

Voiceover narrative figures prominently in the storytelling. “Every shot is cut into the animatic so it has the piece of narration that goes with it as well as the music ideally. Some of that [narration] is scratch and some of it is filled with the real stuff as we go,” Lewis remarks. “You will listen to the narration for every shot that is only five to 10 seconds long. You will time your animation out and express your character differently, depending on what the narrator is saying. They play into each other.” A rhythm gets established with the animation. “Each character will start to lend itself to different expressions and movements. The actor’s voice is a huge guide for that. As an animator, you find that some things are working and keep doing them. Some things don’t work, so you might cut back. Between all the animators, we talk and look at each other’s work. Slowly, a language of that character will develop. Because Grace doesn’t have confidence, she’s often got her hands tucked up to her chest, has her arms in and holds herself tightly. I talked to the animators about how much tension was in the character. Gilbert is bolder, so he’s more likely to be striking big poses with his arms out. Adam has nuanced rules about how he likes each character to look and move when it comes to the blinks and shapes of their eyelids. Certain things make characters look like Adam Elliot characters.”

One of the nine stages had an under-camera rig where a camera could swing down onto a glass tabletop. “Every time an animator had some downtime, they would go onto that stage and do a bit of effects work,” explains Production Manager and VFX Supervisor Braiden Asciak. “The fire was orange and yellow cellophane, and the smoke was cottonwood. They would do these effects, sometimes to the shot. They’d load the shot we had completed into Dragonframe as a reference and animate those effects elements on top of the animation they had already animated prior. It meant that quite a few of the elements we shot were specific to the shot. However, we could reuse certain elements from those other shots.” The visual effects team consisted of Asciak, Visual Effects Editor Belinda Fithie, Gemila Iezzi [Post Producer at Soundfirm) and four to five digital artists at Soundfirm. “They were simple 2D visual effects, so we didn’t need Maya or Houdini. The visual effects artists mostly used Nuke or DaVinci Resolve – Fusion [a node-based workflow built into Resolve with 2D and 3D tools].”

The church burning-down sequence was challenging but rewarding. “Once we shot all the plates we needed throughout that sequence, we put it into the timeline. Everything was worked out together,” Asciak states. “How was Gilbert going to move around that church? Then we slowly animated the effects elements. Once we finished production, John Lewis spent several weeks doing as many effects elements as possible. We built an extensive effects library of cellophane fire, and he did two big shots – one of Gilbert in the church – and did some compositing in Adobe After Effects himself. Then, John did an exterior shot of the church on fire with the huge fire bursting out of the roof. When John left, it was up to me to layer out the rest of that sequence and ensure continuity. I was doing everything in DaVinci Resolve. Some shots have 15 layers of fire, smoke and embers to try to get it right to a level that Adam was happy with, and it looked compositionally right.”

Creating a sense of peril was critical for the moment Gilbert attempted to rescue a snail in the middle of a busy road. “We had a number of cars animated on greenscreen so we could composite those in later,” Asciak reveals. “But the angle of those plates wasn’t matching the shots. Adam wanted the cars going in from the left and out from the right to speed by. You had to match that up with the performance to avoid covering the key moments of a laugh or yell. I spent a good two-to-three weeks trying to time all those cars and each of those shots. Also, we didn’t have any sound at that point, so the sound was done to the visual effects work. I felt like we needed to amp up the intensity of that sequence and bolster it with a lot of cars. One way of doing that was [to transition between shots] using side swipes with the light poles, or there was a van that drove by. That was a good way to improve the cutting in the sequence to make it flow and feel chaotic.”

Close attention had to be paid to ensure all the rigs were painted out. “If there was an element of the shot before the rig appeared, then we wouldn’t need a clean plate,” Asciak states. “But for something like Pinky tap-dancing on a table doing the burlesque, we had to go frame-by-frame and paint out that rig from the mirror. In some cases, it’s a little sliver of a rig. When she’s in the pineapple suit and holding out the plate of pineapple chunks, there is a rig that is like a straight line behind her. If you weren’t paying attention, you probably wouldn’t have noticed, but there was a sliver of a rig, and even the visual effects artists asked, ‘Where is the rig?’

Grace’s bedroom had the most scenes, which were shot chronologically. “That set was there for 16 weeks, over half of the shoot period. It goes from being empty to being full of [snail memorabilia], then we return to it being empty. When Grace is sitting in her bed and says she is surrounded by her snail fortress and the camera pulls out, as soon as we finished that shot, we pulled everyone into the kitchen where we had the TV screening room. We watched that shot together for the first time, and it was magical. At that point, we knew we had something on our hands, as we could clearly see the work of the art, animation, lighting and camera departments.”