By BARBARA ROBERTSON

By BARBARA ROBERTSON

This year’s Best Visual Effects Oscar contenders display a full range of visual effects from invisible effects supporting dramatic stunts and action to full-blown fantasies with a few superheroes and anti-superheroes in between. Visual effects artists created all four elements for these films – dirty, earthy effects; creatures, characters and vehicles flying through the air; fire and its after-math; and amazing water effects. VFX also supported an immersive, unflinching reality for a documentary-style film; immersive, fanciful, beautiful other worlds with talking animals, realistic animals and unusual characters; a love story or two tucked into a spectacle; a thriller; and inside a fable, a warning for our times.

Many of the films have an extra challenge: to go one better than before. Wicked: For Good is a sequel to last year’s Best Visual Effects Oscar nominee and Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning is a sequel from the year before. There are also sequels for other previous award winners: Superman won a Special Achievement Award for visual effects in 1978; The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1998) and Superman Returns (2006) received Oscar nominations. Three previous Oscar winners launched sequels last year: Avatar, Avatar: The Way of Water and Jurassic Park, as did the Oscar-nominated Tron.

Only two highlighted films are not sequels: Warfare and Thunderbolts*, although Thunderbolts* is part of a continuing Marvel Universe story. Here, leading VFX supervisors delve into stand-out scenes that elevated eight possible 2026 Oscar contenders. Strong contenders for Oscar recognition not profiled here include Mickey 17, The Fantastic Four: First Steps and The Running Man, among others.

WICKED: FOR GOOD

Industrial Light & Magic’s Pablo Helman, Production Visual Effects Supervisor for Wicked: For Good, earned an Oscar nomi-nation last year for Wicked, which was filled with complex sets, characters, action sequences and animals enhanced with visual effects. According to Helman, that was just the beginning.

“Before, we had an intimate story full of choices,” Helman says. “Now, it opens up to show the consequences of those choices within the universe of Oz. We shot as much in-camera as possible and still have around 2,000 visual effects shots. But the scope is a lot bigger. This film has everything – special effects, practical sets and visual effects all working together. We see Oz with banners all over the territory. We have butterflies, a huge monkey feast, a grown-up lion, train shots, new Emerald City angles, the Tin Man and Scarecrow transformations, crowds, girls flying on a broom among the stars, rig removal, environment replacement, a mirrored environment, a tornado, hundreds of animals…” Animals with feathers and fur, talking animals, animals that interact with actors, hundreds of animals in set pieces and an animal stampede.

As in the first film, the Wizard is out to get the animals. “We listen to the animals’ thoughts when they’re imprisoned; to what happened to them,” Helman says. “We developed new techniques for them and adopted a different sensibility when it came to animation. Action films typically let the cuts control the pacing and viewer focus. But for this film, thanks to Jon M. Chu [director] and Myron Kerstein [Editor], we were able to take the time we needed to get characters to articulate thoughts.”

Animators used keyframe and motion capture tools. Volume capture for shots within big practical sets helped the VFX team handle crowds of extras. ILM, Framestore, Outpost, Rising Sun, Bot, Foy, Opsis and an in-house VFX team provided the visual effects.

One of the most challenging sequences is when Glinda (Ariana Grande) sings in a room with mirrors. “We had to figure out how to move the cameras in and out of the set, which is basically a two-bedroom apartment, during the three-minute sequence,” Helman explains. “We had to show both sides, Glinda and her reflection. We had to move the walls out, move the camera to turn around, and simultaneously put the set back in. Multiple passes were shot without motion control. Sometimes, we used mirrors. Sometimes, they were reference that we replaced with other views. It was very easy to get confused, and we didn’t have much leeway. It was all tied to a song, so we had to cut on cues. It took a lot of smart visual effects.”

The crew used Unreal Engine to interact and iterate with production design, to look at first passes, to conceptualize, and previs and postvis the intricate shots in the film. For example, in another sequence, Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo) flees on her broom through a forest to escape the Wizard’s monkeys. The crew used a combination of plates shot in England and CG. But it’s more than a chase scene. “She escapes without hurting anyone,” Helman says. “That’s part of the character arc for the monkeys. In this movie, they switch sides.”

Wicked: For Good has a message about illusion that was important to Helman. Glinda’s bubble is not real. The Wizard is not real. “And he lies a lot,” Helman adds. “One thing I like about this film is the incredible message about deception. And hope. Elphaba tries to persuade the animals not to leave. But they take a stand; they decide to exit Oz. That’s married to the theme of deception and what we can do about it. It’s such a metaphor for the time we’re living in. It’s very difficult to go through this movie and not get emotional about it.”

WARFARE

Warfare, an unflinching story about an ambush during the 2006 Battle of Ramadi in Iraq, has been described as the most realistic war movie ever made. Former U.S. Navy SEAL Ray Mendoza’s first-hand experience during the Iraq war grounded directors Mendoza and Alex Garland’s depiction. The film embeds audiences in Mendoza’s fighting unit as the harrowing tale unfolds in real time. While critics have praised the writers, directors and cast, few mention the visual effects. “The effects weren’t talked about at all,” says Cinesite’s Production Visual Effects Supervisor Simon Stanley-Clamp. “They are entirely invisible.” In addition to Cinesite’s skilled VFX artists, Stanley-Clamp attributes that invisibility and the accolades to authenticity. “Ray [Mendoza] was there,” he notes. “He knew exactly what something should look like.”

Cinematographer David J. Thompson shot the film using hand-held cameras, cameras on tripods and, Stanley-Clamp says, a small amount of camera car work. “We did have a crane coming down into the street for the ‘show of force,’ but that was the only time we used a kit like that,” he says. The action takes place largely within one house in a neighborhood, and what the trapped SEALs could see outside – or the camera could show. In addition to a set for the house, the production crew built eight partial houses to extend the set pieces. These buildings worked for specific angles with minimal digital set extension. Freestanding bluescreens and two huge fixed bluescreens were also moved into place. Later, visual effects artists rotoscoped, extended the back-grounds, added air conditioning units, water towers, detritus and other elements to create the look of a real neighborhood.

“For city builds, we scattered geometry based on LiDAR of the sets,” Stanley-Clamp says. Although the big IED special effects explosion needed no exaggeration, the crew spent two days shooting other practical explosions and muzzle flashes for reference. During filming, the actors wore weighted ruck-sacks and used accurately weighted practical guns. “We shot 10,000 rounds of blanks in a day during the height of the battle sequence, and we had a lot of on-set smoke,” Stanley-Camp says. In post, the visual effects crew added the muzzle flashes, tracer fire hits and more smoke, again with authenticity foremost. “Ray [Mendoza] knows how tracer fire works, that it doesn’t go off with every bang,” Stanley-Camp says. “The muzzle flashes were in keeping with the hardware being used. In the final piece, we almost doubled the density of smoke. There’s a point where there’s so much smoke that two guys could be standing next to each other and not know it.” Cinesite artists created simulated smoke based on reference from the practical explosions, added captured elements and blended it all into the live-action smoke.

Cinesite artists created jets flying over for the ‘show of force’ sequence, following Mendoza’s specific direction. To show over-head footage of combatants moving in the neighborhood, the crew used a drone flying 200 feet high and shot extras walking on a blue-screen laid out to match the street layout. “Initially, we were going to animate digital extras,” Stanley-Clamp says. “But Alex [Garland] said no. People would know they were CG. And he was right. Even with 20-pixel-high people, your brain can tell.”

Warfare could not have been made without visual effects. “The set would never have been big enough,” Stanley-Clamp says. “The explosions would probably have been okay, but they would have had to re-shoot many things. The bullets wouldn’t have landed in the right places. They wouldn’t have been allowed to fly the jets over in a ‘show of force.’ The visual effects supported the storyline throughout. He adds, “This isn’t a 3,000-shot show; the discipline was different. We had such a tight budget to work with and did not spend more than we were allowed. But what is there is so nicely crafted. I’ve never been on such a strong, collaborative team.”

TRON: ARES

At the end of the 2010 film Tron: Legacy, Sam Flynn escapes the Grid with Quorra, an isomorphic algorithm, a unique form of AI, and this digital character experiences her first sunrise in the real world. Neither Sam nor Quorra is listed in Tron: Ares, but the Grid has made the leap into the real world in the form of a highly sophis-ticated program named Ares, who has been sent on a dangerous mission. In other words, the game has entered our world – a world very much like Vancouver, where the film was shot.

“From day one, from the top down, everyone agreed to anchor the film in the real world,” said Production Visual Effects Supervisor David Seager, who works in ILM’s Vancouver studio. For example: “Our big Light Cycle chase in Vancouver in the middle of the night was with real stunt bikes.” The practical Light Cycle, though, was not powered; it was towed through the streets, with a stunt performer on the back, and later supplemented with CG. “The sequence is a mix and match with CG, but these are real streets, real cars,” Seager says. “We put Ares into that. If we cut to an all-CG shot, it’s hard to see the difference.”

In addition to filming in the real world, real-world sets helped anchor the Grid’s digital world; there are multiple grids where digital characters and algorithms compete in games and disc wars. “In the Grid worlds, first we tried to match Legacy, then tried to plus it up,” Seager says. “Our Production Designer, Darren Gilford, was the Production Designer on Legacy. We carried that look into this film. Everything has a light line component to it.” As before, most characters wear round discs rimmed with light on their backs. Ares wears a triangular disc. Light trims all the suits and discs. “All the actors and stunt players had suits with LEDs built into them,” Seager says. “The suits were practical, made at Weta Workshop. Pit crews could race in to fix wiring, but in a small percentage of cases, when it would take too long, we’d fix it in CG.” Light rims elements throughout the Grid: blue in ENCOM, the company that believes in users; red in the authoritarian Dillinger Grid. Ares, the Master Control Program of the Dillinger grid, is lit with red.

“Tron: Legacy has a shiny, wet look, and it felt like the middle of the night,” Seager says. “We have that in the Dillinger Grid. To make the Grids seem more violent, we literally put a grid that looks like a cage in the sky – blue in ENCOM, red in Dillinger.” In the digital world, as characters get hit, they break into CG voxel cubes that look like body parts. In the real world, Ares crumbles into digital dust. In the Grid, digital Ares can walk on walls; when Ares moves into the real world, he obeys real-world physics.

SUPERMAN

For Stephane Ceretti, Overall Visual Effects Supervisor, there was as much work in the latest Superman as any visual effects supervisor might wish for. There’s Superman himself, lifting up entire buildings with one hand to rescue a passer-by, flying to the snowy, cold Fortress of Solitude to visit his holographic parents, battling the Kaiju, saving a baby from a flood in a Pocket Universe, having a moment with Lois while the Justice League battles a jellyfish outside the window. And that’s far from all. There’s much destruction. Buildings collapse. A giant chasm rifts through a city. There’s a river of matter. A portal to another world. A prison. Lois in a bubble. And a dog, a not very well-behaved dog, that likes to jump on people. Superman’s dog, Krypto, is always CG. “[Director James Gunn] gave us videos and pictures of his dog Ozu, a fast-moving dog with one ear that sticks up much of the time,” Ceretti says. “Framestore artists created our Krypto, gave him a cape, and replaced Ozu in one of James’ videos. When we showed it to him, he said, ‘That’s my dog. It’s not my dog. But it’s my dog.’”

In terms of other visual effects, there were three main environments. Framestore artists mastered the Fortress of Solitude sequences filmed in Svalbard, Norway, including the giant ice shards that forcefully emerge from the snow, and the robots and holographic parents inside. Legacy supplied the robots on set, some of which were later replaced in CG, particularly for the fight scenes. The holograms were another matter. “They needed to be visible from many different angles in the same shot,” Ceretti says. “Twelve takes with 12 camera moves. It would be too complicated to use five different motion control rigs shooting at the same time. I didn’t want to go full CG because we would have close-ups. So, I started looking around.” He found IR (Infinite-Realities), a U.K.-based company that does spatial capture, rendering real-time images 3D Gaussian splats, fuzzy, semi-transparent blobs, rather than sharp-edged geometry, to provide view-dependent rendering with reflections that move naturally with the view. “They filmed our actors with hundreds of cameras then gave us the data,” Ceretti says. “We could see the actors from every angle in beautiful detail with reflections, do close-ups of the faces and wide shots. It was exactly what we needed.”

For the Metropolis environments, ILM artists handled sequences set early in the show, the final battles in the sky at the end, and all the digital destruction as buildings fall like dominoes into a rift. “The rift and the simulation of the buildings collapsing and reforming at the end was really tricky,” Ceretti says. The production crew filmed those sequences in Cleveland. But, to set the Metropolis stage, the ILM artists built a 3D city based on photos of New York City, integrated with pieces of Cleveland, using Production Designer Beth Mickle’s style guide. “We tried to avoid bluescreens as much as we could,” Ceretti says. “We wanted to base everything on real photography as much as possible. So, we created backdrops in pre-production that we could use as translights for views outside the Luther tower.”

For a tender moment between Superman and Lois, ILM used views of Metropolis outside the apartment window on a volume stage to project a fight between the Justice Gang and a jellyfish on an LED screen. “We used that as a light source for the scene,” Ceretti says. “They could feel what was going on outside, and we could frame it with the camera. It was the perfect way to do it.”

Weta FX managed sequences with the Justice Gang taking charge of the travel to, from and inside the weird Pocket Universe. Production Designer Beth Mickle helped Ceretti envision the otherworldly River Pi in the Pocket Universe. “When I read the script, I saw that James [Gunn] wrote next to the River of Pi, ‘I don’t quite know what that looks like,’” Ceretti says. “We suggested basing it on numbers, and Beth came up with the idea that differently sized cubes, each size representing a unit, would create the river flow.” On set, the special effects team filled a tank with small buoyant, translucent, deodorant plastic balls that Superman actor David Corenswet could try to “swim” through. Later, Weta FX artists rotoscoped the actor out, replaced the balls with digital cubes and added the interaction. They kept Corenswet’s face but sometimes replaced his body with a digital double to successfully jostle the digital cubes.

“We constantly moved between CG characters and actors in this film,” Ceretti says. “To suggest speed, we’d add wind to the hair and sometimes have to replace hair, and make the cape flap at the right speed to feel the wind. But I really tried to have the actors be physically there. As always, it’s a combination of real stuff, CG, digital doubles, and going from one to the other and back and forth all the time.”

THUNDERBOLTS*

“This film is the opposite of everything I’ve been asked to do in the last 10 or 15 years,” says Jake Morrison, Overall Visual Effects Supervisor on Thunderbolts*, whose 35 film credits include other Marvel films. “Most of the visual effects I do are about spectacle, world-building, planets and aliens,” he says. “Jake Schreier, the director of Thunderbolts*, had the exact opposite brief. He wanted it to feel as organic as possible, grounded, real.”

Thunderbolts*’ unconventional and at times dysfunctional team of antihero characters resonated with critics who hailed the Marvel Studios’ film as a “return to basics.” “Basics” reflects the approach taken for many visual effects techniques. For example, on a practical level, it meant ditching bluescreens for set exten-sions to achieve a more natural tone – and doing without LED volumes. “Any time we couldn’t afford to do a set extension, I asked the art department to build a plug in the right color for what will be in the movie,” Morrison says. “It took a minute for the team to understand, but it had an incredible ripple effect. You’d look at a monitor live on set and see a finished shot even though there would be set extensions later. It felt like a movie. The amazing thing was that we didn’t have to change skin tones and reflectance. I would say the set extension work was more real because it was additive, not subtractive.”

In that same vein, rather than filming in an LED volume, Morrison used a translight on set for a view out the penthouse in Stark Tower, which in this film has 270 degrees of glass windows wrapping it, a shiny marble floor and a shiny ceiling. “A team from ILM shot immensely high-detail stills of the MetLife building in New York to create an impressive panorama that we printed on a vinyl backing 180 feet long,” Morrison says. “With a huge light array behind the vinyl, the photometrics were correct. One of the guys walked on set and wobbled with vertigo.” Visual effects artists replaced the translight imagery in post, adding areas hidden by the actors standing in front of the vinyl when necessary. “But every reflection in the room was exactly right,” Morrison says. “It’s the same idea as an LED volume, but the color space differs. There’s nothing like the flexibility you get with LED volumes, but there’s something that feels genuinely organic when you backlight photography at the right exposure.”

Throughout the shoot, Morrison worked with production and special effects to have them do as many effects practically as possible, even when a CG solution might have seemed easier.Offering CG as a safety net in case the practical effects didn’t work helped convince them. “I was able to give Jake [Schreier] shots of the lab sequence, and he couldn’t tell which were plates and which were CG,” Morrison says. “You can only do that if you commit production to build it for real. Then, you can scan that and have it as reference, and you can do stuff with it. We can shake it. Every glass vial rattling and falling, the ceiling cracking, all looks real because we pushed for it to be real. It all becomes subjective if you don’t have that reference on a per-frame basis.”

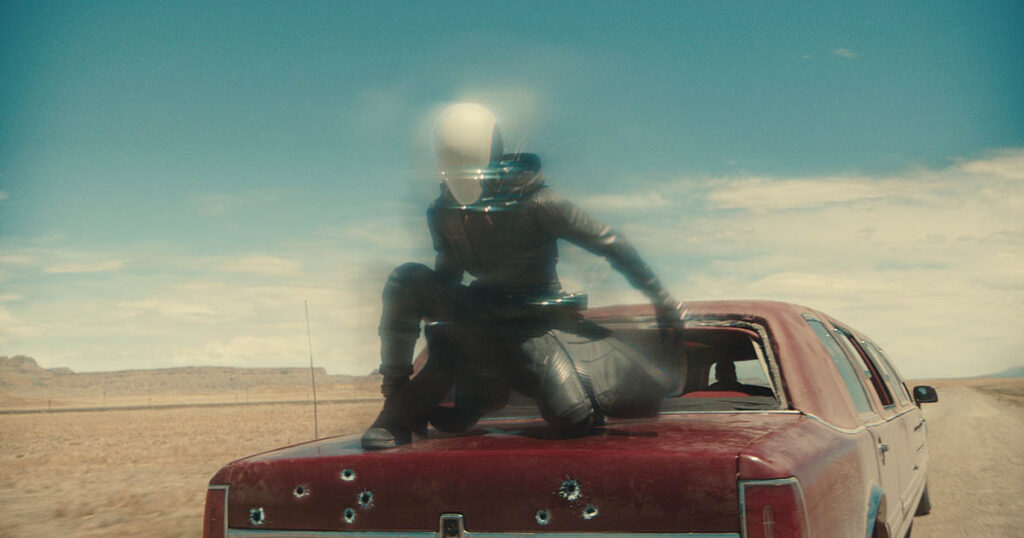

For a driving sequence, he convinced the crew to take a “’50s” approach rather than work in air-conditioned bliss in an LED volume. Instead, they filmed in the Utah heat. “Everyone knows there’s a crutch,” Morrison says. “It’s easier to change the LED walls. But something old school brings a level of reality.” For motorbike work in that sequence, rather than painting the stunt biker’s large safety helmet blue or green to replace it with CG later, Morrison had the helmet painted the color of the actor’s skin and glued a wig on it. “People on the show thought I was kinda nuts,” Morrison says. “It looked so funny, we didn’t have a dry eye in the house. But we shrank down the oversized helmet and hair by 25% and had an in-camera shot. Just because you could go all CG doesn’t mean you should. You should use VFX for things that need it, not for things that could be practical.”

Even when characters in the film transform into a void, Morrison looked for practical possibilities. “Jake and Kevin [Producer Kevin Feige] would challenge me with ‘How would you do this character if you didn’t have CG?’” Morrison says. “We came up with three types of voiding, each of which could have been done with traditional techniques.” For one, they used what Morrison calls a simple effect that is difficult to pull off: They shot actor Lewis Pullman, rotoscoped his silhouette, zeroed it back until it looked like a hole in the negative, then had each frame show just enough detail to be scary. For the second, they projected shadows out from a character as if it were a light source, using aerial plates shot in New York. For the third, they zapped characters out of the frame and splatted their shadows onto the ground in the direction from which they’ve been zapped. “The effect we created is very old school visually, but we used all modern techniques. It’s really good to be put in a box sometimes,” he adds. “It’s an exercise in restraint. Sometimes, the playground is a little bit too big. Being able to unleash that creativity is fun. If people like the work we did, it’s because we tried so hard for you not to notice it.”

MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE – THE FINAL RECKONING

Visual Effects Supervisor Alex Wuttke received a Best Visual Effects Oscar nomination and numerous other awards in 2024 for Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One. The effects in this year’s follow-up film, Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning, could provide the same accolades. Production Visual Effects Supervisor Wuttke, who is based in ILM’s London studio, says, “We were successful last time. So, we took what worked and extended it. We wanted to take it to the next level.” This film has 4,000 VFX shots, and as in previous MI films, actor Tom Cruise anchored everything. “He pushed himself,” Wuttke says. “We’re his enablers. His desire to up the ante drives the rest of us to be innovative.”

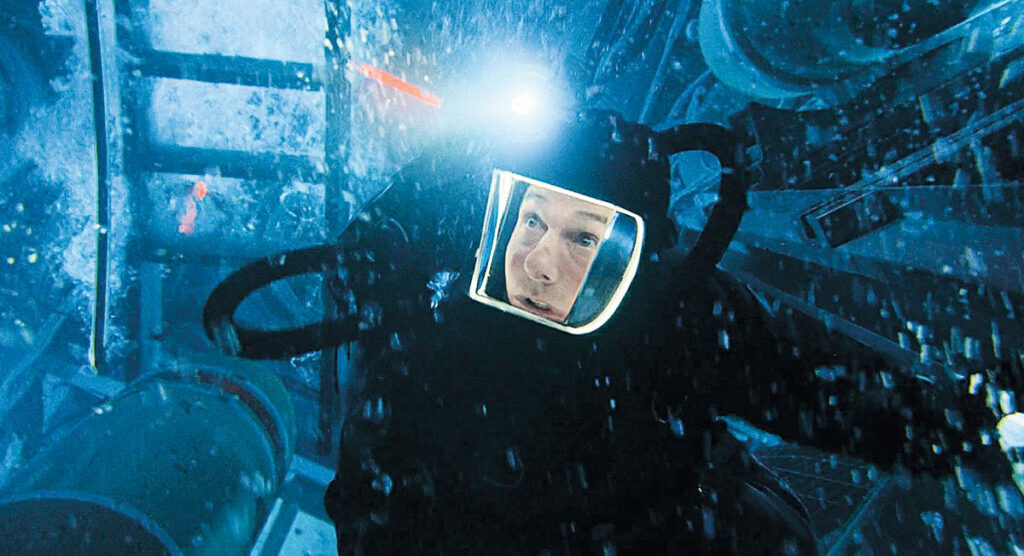

Two big sequences illustrate the tight interplay between special effects and visual effects: the submarine and biplane sequences. For both, the crews looked for ways to help Cruise perform the scenes realistically. For example, Cruise’s character, Ethan Hunt, must navigate around moving torpedoes while inside a partially flooded, rotating submarine. Special effects built a giant gimbaled submersible that Cruise drove inside in a deep dive tank. The Third Floor’s previs team mapped out the action. The actions and the range of motion dictated the rig that was built. All the water inside the submarine is real. “There were so many moving parts,” Wuttke says. “We had to drop torpedoes around Tom’s perfor-mance. Sometimes that was not possible within the chaos of Tom being inside a washing machine. We knew we would need repeat passes.” When it wasn’t safe practically, CG torpedoes hit with the right impact, and water simulations sold those shots. Even when the action was real, the water, filtered for health and safety, needed digital enhancements. CG particulate, bubbles and so forth added reality, scale and scope.

“One of my favorite sequences is the biplane sequence at the end that we shot in Africa,” Wuttke says. In this sequence, Cruise hangs onto the wing of a biplane while it performs aerobatics. “It was so complicated working out how we would execute those sequences, “Wuttke says, “but it was hugely rewarding. The visual effects work is seamless, and Tom was astonishing. We would have a pilot in a green suit flying the plane, and Tom would be holding on.” The VFX teams removed the pilot and the safety rigging. They also replaced backgrounds for pick-up shots – gimbal work filmed in the U.K. – with the African environment.

Several VFX studios worked on the film, including Bolt, Rodeo FX, Lola, MPC and ILM. “Our chief partner was ILM. They were amazing,” Wuttke says. “Jeff Sutherland, Visual Effects Supervisor, was incredible. Their Arctic work with the blizzard was phenom-enal. We were worried about the sequence when Hunt confronts the entity, but we were very pleased with the CG work created jointly by ILM and MPC. Hats off to Kirstin Hall, who picked up MPC’s work and finished it at another house without missing a beat.”

“We’ve talked about the big sequences, but we had close to 4,000 shots,” Wuttke adds. “A lot of work might not be noticed. We amassed a huge amount of material.”

JURASSIC WORLD: REBIRTH

ILM’s David Vickery, Production Visual Effects Supervisor on Jurassic World: Rebirth, received two VES Award nominations for 2023’s Jurassic World: Dominion. Rebirth was more challenging. “This film presented us with so many new technical and creative challenges that it’s hard to compare from a complexity standpoint to any film I’ve worked on before,” he says. From pocket-sized dinosaurs to T. rex, Mosasaur, Spinosaur, Mutadon, Titanosaur, Quetzalcoatlus dinosaurs and more. Water in rapids, water in open ocean, water on dinosaurs, boats in water, dinosaurs in water, people in water, white water, waves, splashes. Capuchin monkeys. Inflatable raft. Digital limbs. Jungles. Titanosaur plains. Filming in wildly remote locations. All within a short production schedule – 14 months from the first meetings with director Gareth Edwards to final delivery.

ILM’s work on the dinosaurs was an example of its ability to deliver the director’s vision. Edwards’s shooting preference – long, continuous action pieces – isn’t conducive to animatronics. “For the first time, we didn’t match the performance of practical animatronics,” Vickery says. “Gareth wanted our dinosaurs to be entirely digital and behave like real animals, not just turn up on screen, hit a mark and roar. We all agreed never to produce a piece of dinosaur animation without finding specific live-action reference of real animals in that situation. Our animators at ILM stuck to this plan and it worked beautifully.” Then, given concept approval for the dinosaurs, artists used the new tools to manipulate the creatures’ soft tissue – skin folds, neck fat, cartilage and so forth. To boost realism and add fidelity to the creature simulations, a new procedural deformer that puts high-resolution dynamic skin-wrinkling on muscle and fatty tissue simulations, removing the previous limitations of 3D meshes. The output, a per-frame point cloud with normal-based displacement information, could be read back into look development files.

“We worked on any part of the creature that wouldn’t have been preserved in the fossil records,” Vickery says. “Things that could give our dinosaurs unique personalities, yet wouldn’t contradict current scientific understanding. The new tools gave us an incredible level of detail in our creature simulations and brought a physical presence and level of realism to the dinosaurs that the franchise hadn’t seen yet.” That same level of realism and the opportunity to create new tools extended to the CG water. “There was a huge focus on realism for all the water in Rebirth,” Vickery says. “It was our main concern from the start and one of our biggest technical and creative challenges.” CG Supervisor Miguel Perez Senent, working with Lead Digital Artist Stian Halvorsen, developed a broad suite of tools, including a new end-to-end water effects pipeline based on a wrapper around Houdini’s FLIP solver with custom additions for efficiency and realism. Low-res sims defined the overall behavior of a body of water and guided higher resolution FLIP sims to enhance details where collisions and interactions took place. A mesh-based emission from the resulting water surface provided fidelity in secondary splashes from areas churned up in the main simulation.

“The biggest innovation was a new whitewater solver that handled the complex behavior of splashes,” Vickery says. “The details in these simulations are second to none. You can see white-water runoff on the dinosaurs fall back down and trigger tertiary splashes when hitting the water surface.” Fewer than 10% of the shots in the final Essex boat sequence feature any real ocean water, and with few exceptions, entire sequences were filmed on dry land in Malta. ILM artists extended the partial build of the boat, created the ocean surface, simulated the boat engines, the whitewater, the wake, crashing bow waves, sea spray, mist, and integrated the Mosasaur and Spinosaur dinosaurs within all that.

“I pushed production to shoot on a real boat at sea, but noise from the boat’s diesel engines made recording sound impossible. In the end, with consistent light on the boat and cast a priority, they used a water tank alongside the ocean in Malta for most of the shots. SFX Supervisor Neil Corbould, VES covered the real Essex with IMU’s (internal measurement units) and recorded how it performed in varying ocean conditions. Then, that data drove a partial replica of the Essex he built and put on a gimbal. “We never filled the Essex tank with water because that made the shooting prohibitively slow,” Vickery says. Similarly, the T. rex rapids were largely CG. “It’s a flawlessly executed, fully CG environment based on rocky rivers we found around the world,” Vickery says. “We replaced everything shot in-camera, except a small section of rocks that the cast grab onto at the end. The inflatable raft is CG. There was complex ground and foliage interaction with the T. rex; shots above and below the water surface, and beautifully choreographed T. rex animation.”

Another invention, a custom VCam system, allowed Edwards and Vickery to shoot real-time previs using Gaussian splats of their remote Thailand locations. Vickery and VFX Producer Carlos Ciudad shot 360-degree footage using an Insta360 camera during tech scouts. Proof Inc. created Gaussian splats from the footage, and Production Designer James Clyne built virtual replicas of the sets inside the Gaussian splats. Then, Proof used Unreal Engine to build a virtual camera with the 35mm anamorphic lens package for the splat scenes and motion capture of stand-ins that allowed Vickery and Edwards to block out and direct action sequences.

ILM handled most of the work on Rebirth’s 1,515 VFX shots with an assist from Important Looking Pirates and Midas. Proof did previs and postvis.

AVATAR: FIRE AND ASH

Much has been written about the groundbreaking, award-winning visual effects and production techniques used to help craft James Cameron’s Avatar (2009) and Avatar: The Way of Water (2022). Indeed, both films earned Best Visual Effects Oscars for the super-visors working on the films, giving Senior Visual Effects Supervisor Joe Letteri, VES of Weta FX his fourth and fifth Oscars. Expect to hear about new groundbreaking tools and techniques for the latest film, Avatar: Fire and Ash, but this time, more emphasis is on artistry than technical breakthroughs.

“This film is a lot more about the creativity,” Letteri says, “about getting to work with the tools we’ve built. We’re not trying to guess how to do something with three months to go. We’ve front-loaded most of the R&D.” He adds, “A lot of times you build the tools, make the movie, then you’re done. You don’t get to go back and say, ‘Gee, I wish I knew then what I know now.’ This film gave us the chance to do that because the films are back-to-back. We look at the second and third films as one continuous run.” For example, much of the live-action motion capture for characters in Fire and Ash was accomplished at the same time as capture for the second Avatar, using techniques pioneered on the first film. “We didn’t shoot anything new since the last film,” Letteri says. However, Fire and Ash introduces a new clan, the Ash people, and a new antagonist, Varang, leader of the Ash people. They, particularly she, provided an opportunity for the studio to further refine its animation techniques. “We have a great new set of characters,” Letteri says. “They allowed all kinds of new emotional paths. Varang [Oona Chaplin] is a bit of a show-off; I really enjoyed scenes with her.”

On prior films, animators used a FACS system with blend-shaped models. Since Way of Water, they have been able to manipulate faces with a new neural-network-based system. “We wanted the face to respond in a plausible way, given different inputs,” Letteri says. “Before, animators would move one part of the face, then move another, and kind of ratchet all the pieces together to make it work. The capture underneath helps unify it, but they have to fine-tune that last level of realism. With the neural network, pulling on one side of the face will affect he other side of the face because the network spans throughout the face. They get a complementary action. The left eyelid might move if they move the right corner of the mouth. It gives the animators an extra level of complexity. It took getting used to because it’s different, but it’s how a face behaves. Once the animators became comfortable with the system, it gave them more time to be creative. The system was easier to work with.”

As for the fire of Fire and Ash, Letteri says, “We’ve done fire before, but not as much as we had on this film. So that was a big focus. Simulations are hard to do, but we do them the old-fashioned way – simulating everything together so the forces are coupled, but breaking layers for rendering to incorporate pieces of geometry. As for the rest, the focus was, ‘We know how to do this. How can we make it better?’”

In addition to the Ash People (Mangkwan), a second new Na’vi clan, the Windtraders (Tlalim), is introduced for the first time – along with their flying machines. Windtraders fly using Medusoids, unique Pandoran creatures, and giant floating jelly-fish-like airships that support woven structures propelled by harnessed stingray-like creatures called Windrays. “The Medusoids were in Jim’s [Cameron] original treatment, and I was bummed when he cut them from the first film,” Letteri says. “But here they are. They’re pretty spectacular. Everything is connected to everything else. We captured parts of it, so we had to anchor that to our craft floating through the air. It was great to work out all the details and set it flying. Jim shoots in native 3D, so when you look at it in stereo, you’ll really be up in the air with these giant, essentially gas-filled creatures. It’s very three-dimensional.”

The crew also began refining their proprietary renderer, Manuka. “We used a neural network for denoising on the second film and real-ized that was okay, but we lost too much information,” Letteri says. “It really belongs inside the renderer, not after the render. So, we started moving those pieces into Manuka, and it’s starting to pay off. There will be more improvements to come.”

Letteri observes, “This film is all about the characters and the people behind them. One of the secrets of this business is that with all the computers and automation, there’s still a fair amount of hand-work that goes into these films. A lot of work by artists is the key to it, which is great because what else would we be doing?”