By TREVOR HOGG

By TREVOR HOGG

There is a microscopic realm within and around us that we often take for granted, but the tiny size does not reflect the significance it plays in creating and sustaining life. Magnifying matters to a more comprehensible level are filmmakers and documentarians who make the most of macro photography to tell compelling stories. In an interesting turn of events, a Pixar-animated movie inspired a National Geographic documentary series, thereby turning A Bug’s Life (1998) into A Real Bug’s Life (2024 to present)! Technology has greatly evolved from the time of Fantastic Voyage (1966), which relied upon practical effects to create a miniaturized ship and crew traveling through a human circulatory system to perform surgery, to CG simulating the insect point of view for Ant-Man (2015). Then there are those driven by personal enjoyment and curiosity, which led to the establishment of the YouTube channel Journey to the Microcosmos (2019 to 2024). All of these scenarios have educated and entertained us about the micro details in a big way.

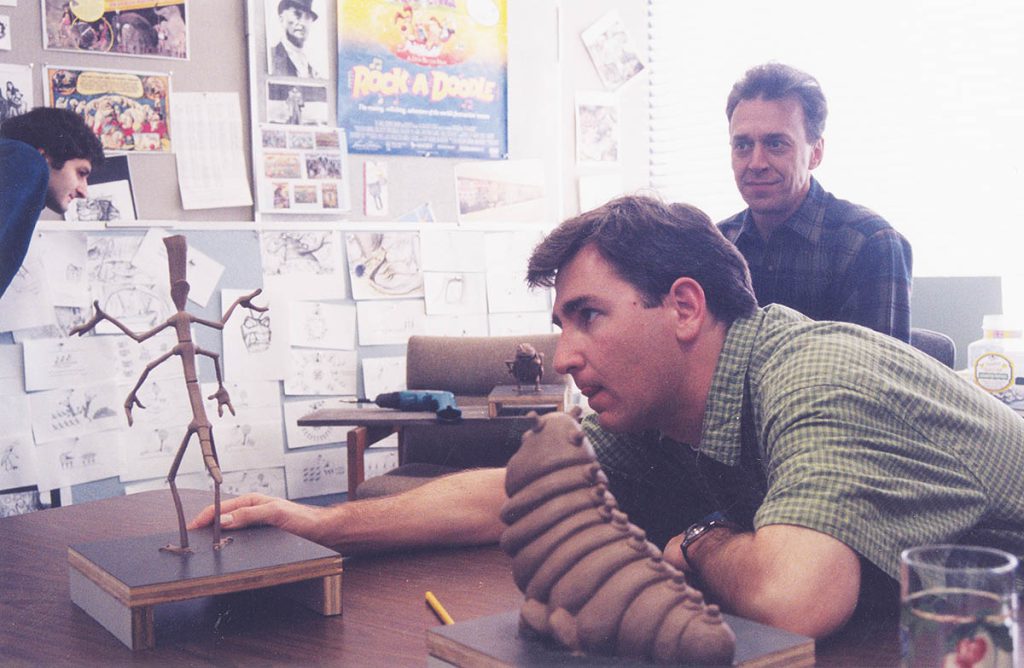

After achieving its first CG-animated feature film, Pixar decided to go from toys to insects with the release of the Seven Samurai– inspired A Bug’s Life. “Neftali Alvarez, a hardware and technical guy here, created the ‘bug-cam’ which was a little circuit board with a tiny camera on it,” recalls Bob Pauley, Art Director on A Bug’s Life. “We put that at the end of a stick, went down into the bushes, ran it around and looked at what the environments were like, as well as the insects. I caught this little beetle, placed it on a turntable that we used for clay sculpting and had a camera set up. We turned it as the beetle moved. I remember looking at the footage afterwards and going, ‘Wow. Look at all of this rich detail and super-tight depth of field.’ It looked small and yet that little bug had so much personality and character.” An ant colony needed to be created. “We ended up with crowds, which we had never done before,” remarks Bill Reeves, Supervising Technical Director on A Bug’s Life. “We had to try to make the animation of those crowds as simple as possible by removing a set of limbs. When we built a crowd, we used different animation libraries to make them feel as if they were different. That was the other thing with the four legs for ants. We decided to have the ants stand up and walk on two legs, so what do we do with that third set of legs?”

Technology had to be modified to achieve the proper sense of scale. “Shaders had to be built at that scale,” Reeves explains. “If you had a shader for a brick and used that in Toy Story, the shading would be scaled for what and how you would see it. If you wanted to reuse that brick in A Bug’s Life, we would potentially have to go back in and re-shade or add much more detailed texture to make it look good at that scale with the camera.” Shading and lighting were significantly improved from Toy Story. “Everything is not plastic in A Bug’s Life. Rick Sayre, VES [Shading Supervisor] and Sharon Calahan [Cinematographer] went off and did a whole bunch of stuff for our shading networks and how lighting interacts with the shading. At the time, it was a significant change to how detailed the shading was and the interaction between shading and lighting.” Scale cues were inserted into the visuals. “When a sprig or leaf of dandelion floats across, it becomes enormous,” Pauley states. “You get to see that world with cues that we know from our world. I remember how hard it was to do those things. Nowadays, it’s not hard to do it. But the payoff was good because it’s all for storytelling. When Flik climbs up on that dandelion, everybody knows what a dandelion is, so you get that scale right away, and you can give drama to it as well.”

When rumors of A Bug’s Life 2 did not materialize, the founder and CEO of Plimsoll Productions, Grant Mansfield, went to National Geographic with a proposal to make a real-life version. “We weren’t copying the movie, but we were using some of the same tropes,” explains Bill Markham, Series Producer of A Real Bug’s Life. “In A Bug’s Life, the leaf falling down is an iconic moment, and that happens in the jungle episode. We got Pixar’s blessing, and they did a beautiful mashup video where their bugs are getting excited about our series. It’s really fun.” A humanistic approach is adopted for the storytelling. “‘Life’s a Beach’ was about growing up, wanting to move out and find a new home, and getting into the property market in a way. Each episode has a theme, and we chose bugs where we could tell their story with that lens on them.” Body doubles appear on the screen. Markham notes, “I don’t think you could stay on a single insect for more than a few hours because you’re going to lose or upset them, and that would be to the detriment of their welfare. The good thing about bugs is they generally are programmed by their biology to do the same things, so you can use different individuals to tell the same story.”

In order to get the lens down on the ground to capture the shots, the camera team for A Real Bug’s Life has had to be resourceful. “Camera movement on that scale is difficult,” states Chris Watts, Cinematographer for A Real Bug’s Life. “A lot of normal cinema lenses don’t have a good minimum focus and are quite big, whereas probe lenses have great minimum focus, and you can get them into small spaces and into their world. We’ve got lenses that are as small as a medical endoscope, which is five millimeters across at its end and were designed to go inside human bodies, so they’re waterproof. Then you’ve got your standard probes that you can get off the shelf.” Probe lenses are compromised optically. “They don’t let a lot of light in because you’re trying to get not much light up a long tube to a camera. The cameras have improved massively with their frame rates, so we can really slow down important moments, and they are much more light-sensitive as well, which allows us to use these complicated lenses.”

Wide lenses came in handy when trying to capture the speedy tiger beetle. “You go, ‘I’m going to film the fastest bug in the world. What do I need? I need a camera that can shoot at the highest frame rate,’” remarks Nathan Small, Producer, Director and Cinematographer of A Real Bug’s Life. “But when Dale Hudson [Assistant Camera] did that, it looked like rubbish, like watching the tiger beetle played back slowly. It just looked clumsy and ungainly. What they actually needed to do was to shoot it at the correct speed, stick with it, and try get as much out of each shot as they could. You’re shooting at real-time, but close with very wide lenses so the shots last for longer.” Some of the scenes required sets being built, such as interior shots of an anthill. “We tried to do as much as is humanly possible outside in the wild. Maybe we need to change the environment a little bit so we can get our cameras in and show people new ways of seeing these things. But unless there’s a really good reason, we try not do things on sets to keep it as real as possible.”

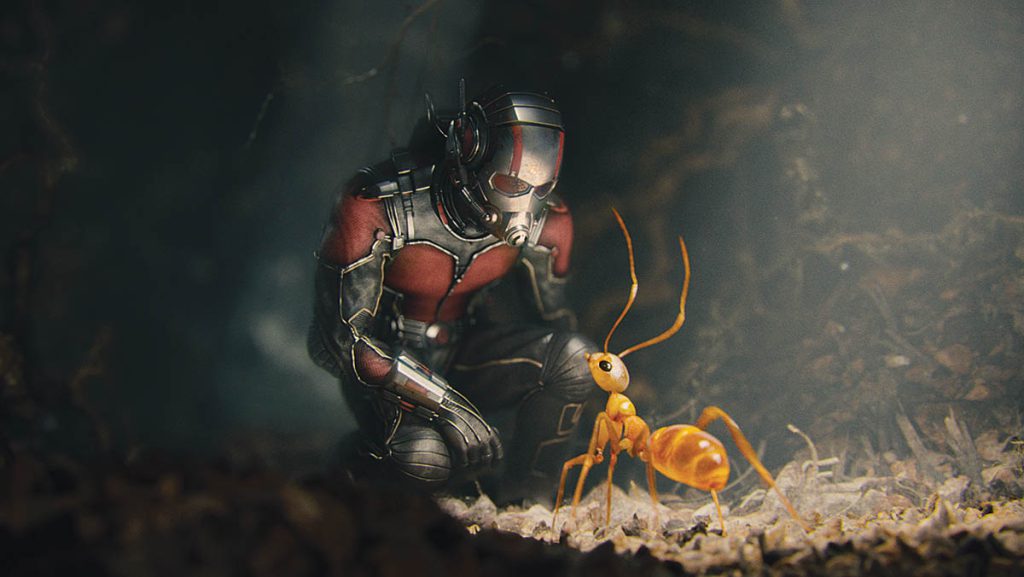

There is definitely a certain feel to macro photography that had to be emulated for an MCU franchise. “Macro photography basically means that the sensor is 1:1, and the amount that you can see in focus goes down to a sliver,” explains Jake Morrison, VFX Supervisor for Marvel Studios on Ant-Man. “You can pour on tons of light, which allows you to open up that sliver; however, at a certain point, you get diffraction, and it falls apart. There are only a certain number of ways you can shoot this. I studied a bunch of stuff. The Saharan silver ant was in a David Attenborough documentary that was particularly interesting. There was some stunning macro photography to the point where you can see the individual hairs on the ant, and that was the level I wanted to get to because, obviously, we had to convey story. The whole point with the ants was that you had to get to empathize with them. To get to that stage, I was rationalizing that they had to be the size of pets.” Tests were conducted with Cinematographer Bill Pope. “We got some macro lenses and shot the ant version of a terrarium. I had all of this photography, which was incredible reference. You get down to the macro level, and you see an astonishing amount of detail on the stuff that you do see in focus.”

Fur proved to be problematic. “When you see something that looks shiny, it is usually covered in fur,” Morrison remarks. “We would call that isotropic in the business, which is to say that all the specular response is along one line. We went straightaway for spherical lenses. When you see anything defocused in any film, there is a particular effect that is a byproduct of the lens called ‘bokeh’ or the circle of confusion. An anamorphic lens squeezes the image, and what happens weirdly is if you have a bright highlight behind you, it looks like an almond. You would think when the image is un-squeezed the bokeh would go wide, but it doesn’t. You never get that with macro stuff. We shot the entire film 1.85:1, and whenever you go into the macro realm, the depth of field compresses deeply. Similarly, if you do a long lens throw, like with a zoom lens, the depth of field compresses completely. Macro is like that but more intense. You could use that as an element of surprise and interest, because my concern was that the background would be completely mushy. I made these customized lens profiles, which at the edges had all these round shapes. If you watch Ant-Man, you see this because it’s a macro motif.”

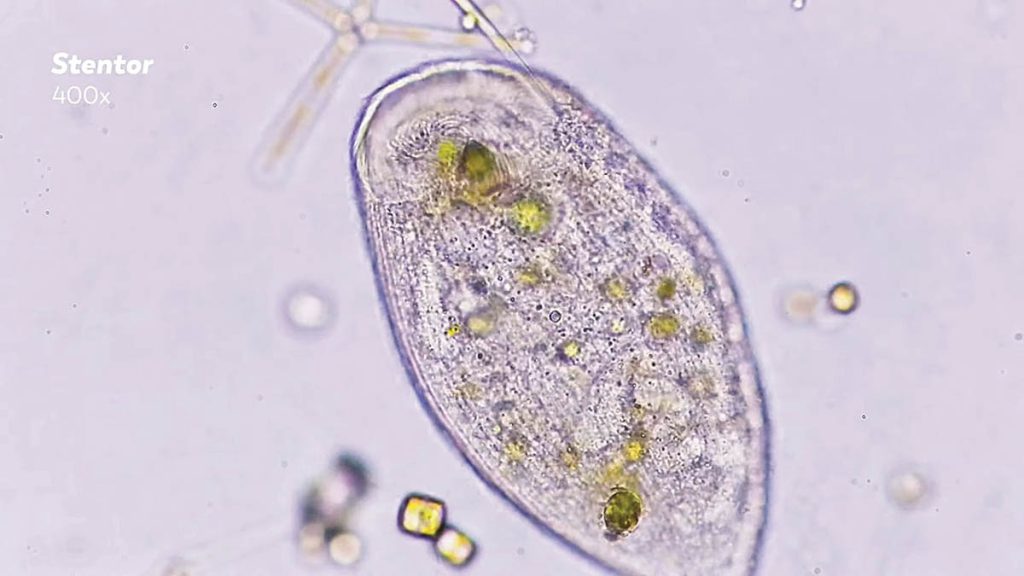

Microbes are even smaller than bugs, but equally fascinating for those responsible for producing Journey to the Microcosmos, with Microscopic Videographer James Weiss making some surprising discoveries with a Fujifilm X-T5 digital camera, a Zeiss Axioscope 5 Smart Laboratory Microscope and Zeiss Objective Plan-Apochromatic 40x-1000x lens. “I relate to these things that I record under the microscope, so they’re a cure for my existential crisis!” laughs Weiss. “Traditionally, you have this microscope, and there is this phototube that you attach to your camera, but I don’t like that structure. I place my Fujifilm camera on a monitor holder, and when I see something under the microscope, I swing the monitor holder arm and record through the eyepiece. This is what I’ve been doing since I started seven or eight years ago.” Weiss has 5,000 hours of footage. “I’ve collected from the same pond for five or six years over 1,000 samples to find one organism, and I found four cells of it in my entire life.”

Like with any cinematography, there is an element of artistry. “It depends on what the production wants from me. Some people want to focus on the microbe in a scientific way while others want to capture an emotion,” Weiss notes. “There was one project about a dying fencer, so for that I needed to use a microbe that extends its neck further away from its body. I misaligned the microscope so you get some scattered light, which is not a proper technique, but it gives you this visual effect. There are hundreds of thousands of things I have to do to get that emotion across.” Microbes are living creatures. Weiss states, “In my house, I have 4,000 jars from different places, and when you put everything in a jar or smaller container, you cannot keep the same environmental conditions for these organisms. They last for a week or two weeks. For most days, I go through a sample for 12 to 16 hours. Drop by drop, you have to check it. This hope for something you want to find is a big dopamine surge, so that keeps me going!”