By TREVOR HOGG

By TREVOR HOGG

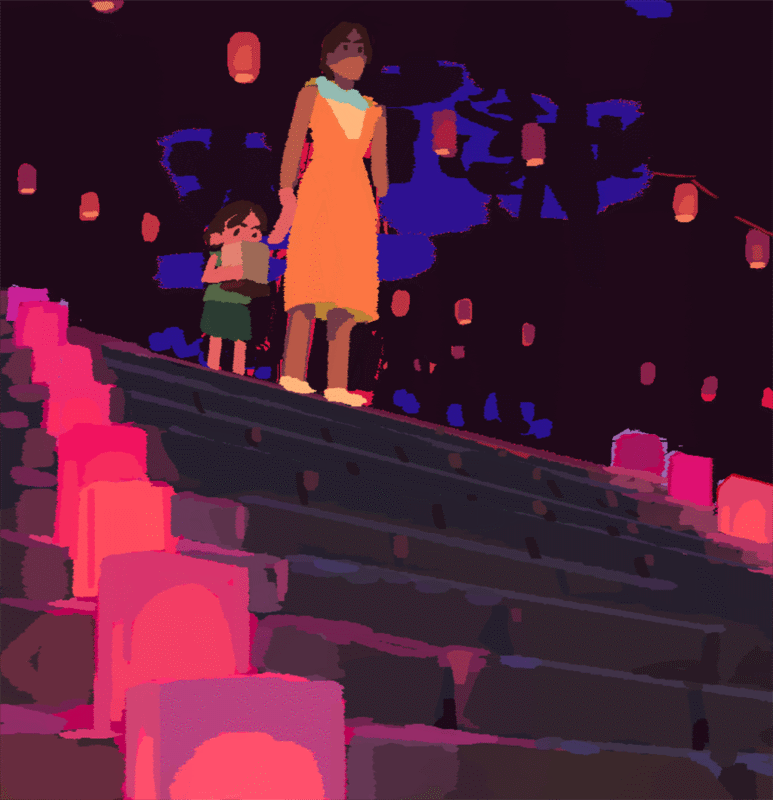

Images courtesy of GKIDS.

Former students at the Gobelins Paris School and storyboard artists on The Little Prince, Maïlys Vallade and Liane-Cho Han decided to share directorial duties for their feature debut Little Amélie or the Character of Rain, which adapts the memoir of Amélie Northomb, who established deep emotional bonds with her paternal grandmother and local housekeeper Nishio-san when her father worked at the Belgian embassy in Japan during the 1960s

“What was interesting for us was to find the best way to tell the story, which was the relationship between Nishio-san and Amélie. We tried to eliminate all of the things that were not relevant to this storyline and rebuilt the story in three acts from the point of view of a young child. We love being really close with the characters.” —Maïlys Vallade, Writer and Director

“Especially on the movies by Rémi Chayé, we worked together on Long Way North and Calamity, Une Enfance de Martha Jane Cannary, and developed our sensibility, cinematography and animation, and found ways to push the screenplay to the maximum,” states Maïlys Vallade, Writer and Director. “The Little Prince was a good exercise for us because we tried many ways to create the scenes that are not exactly as written. What we have in common with Rémi Chayé is that we love to write our scenes just before making the image. Sometimes we made the image before writing.”

Understanding the intention of a sequence is important. “It was with Mark Osborne [director] and Bob Persichetti [Head of Story] on The Little Prince where we learned to not only illustrate the script but to see the sequence as a way into the movie,” explains Liane-Cho Han, Writer and Director, “to think about the character arcs from the beginning to the end, not only in our sequence we are storyboarding. The first advice I had about storyboarding was don’t try to illustrate the script but sell the ideas.”Little Amélie or the Character of Rain was a difficult adaptation. “The Character of Rain is a little book with a lot of themes and is chronological,” Vallade notes. “What was interesting for us was to find the best way to tell the story, which was the relationship between Nishio-san and Amélie. We tried to eliminate all of the things that were not relevant to this storyline and rebuilt the story in three acts from the point of view of a young child. We love being really close with the characters.”

“Especially for this movie, we had to make sure that we’re expressing the character’s emotional state and experiencing it with her not only by the position of the camera but also in the way she breathes and touches things. Even the colors reflect her emotional state. We wanted to make sure that everything connects with her emotion.”

—Liane-Cho Han, Writer and Director

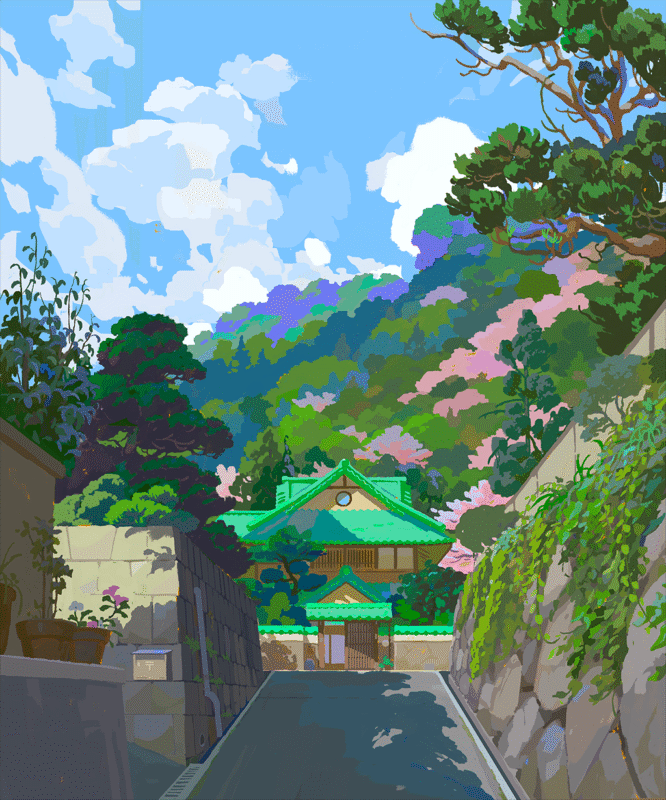

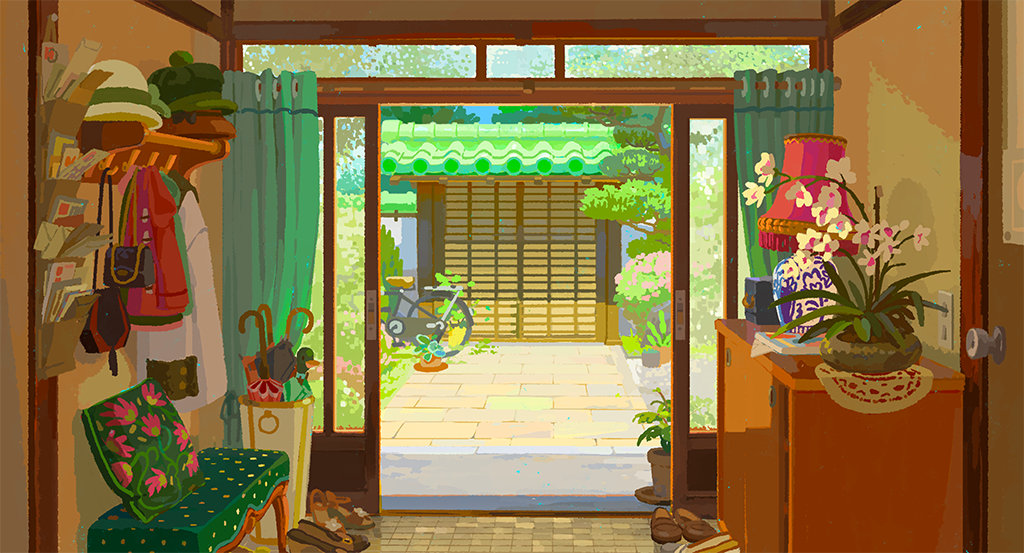

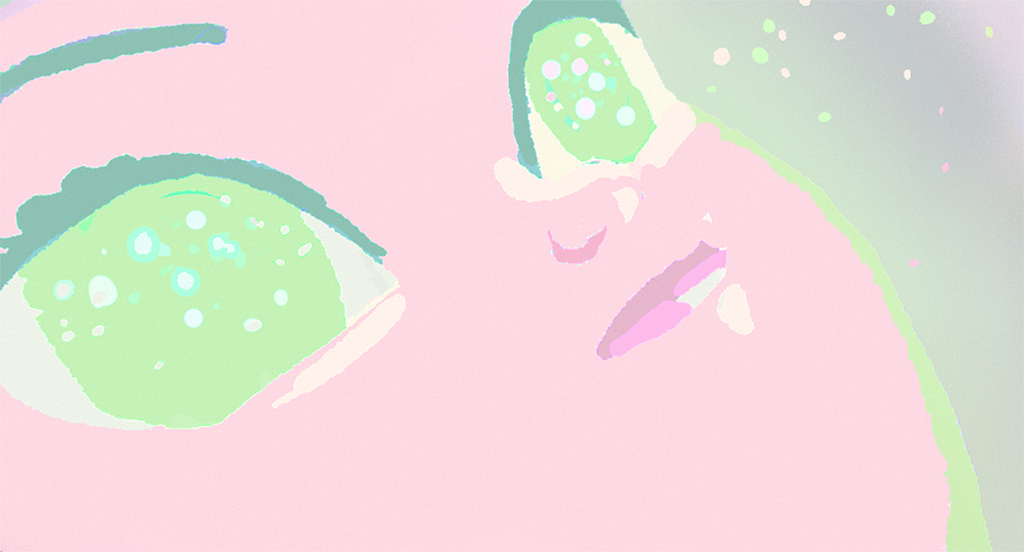

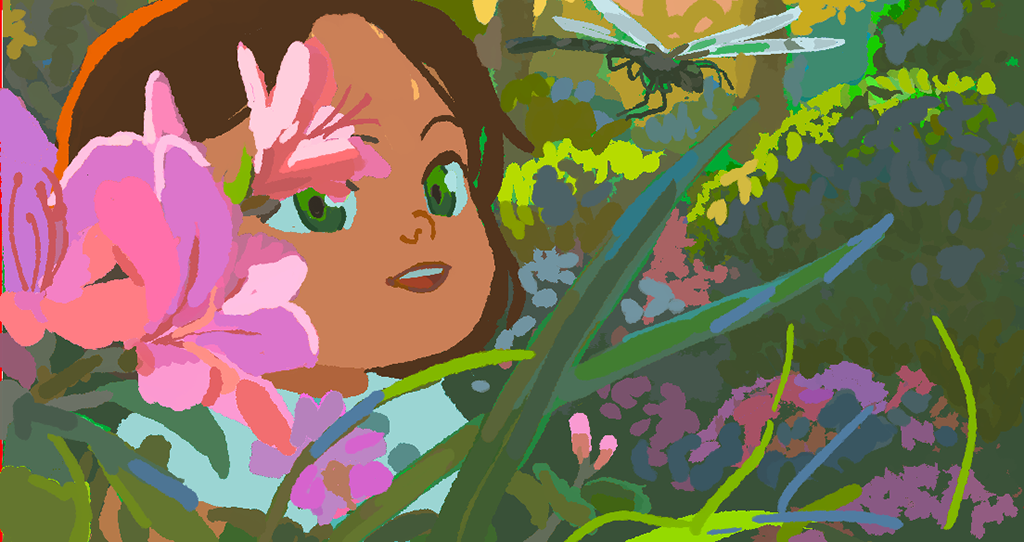

Driving the visual language is having the camera placed at the height of a two-and- a-half-year-old child and having the imagery evoke a sense of wonder. “Especially for this movie, we had to make sure that we’re expressing the character’s emotional state and experiencing it with her not only by the position of the camera but also in the way she breathes and touches things,” Han remarks. “Even the colors reflect her emotional state. We wanted to make sure that everything connects with her emotion.” A particular animation methodology and style were cultivated. “For many years, we have developed this pipeline,” Vallade states. “On my student film I worked with solid colors and without outlines. We wanted to go deeper into the narration process but not to reinvent the wheel. We have worked for many years in this way to have the characters, background and light merge together. There is also this motif of color like a wash painting that conveys the sensibility and naivete of a young child’s gaze.”

While everything in the movie is drawn, a pivotal asset was created in 3D for reference purposes. “90% of the movie takes place at the Japanese house, which is difficult to show because they have a specific proportion, and there was also the matter of time and budget,” Han remarks. “This is why the Japanese house was built in 3D, but it was strictly used as a guide.” As the storyboards were being created, the characters were being designed. “We developed them with Mariette Ren, a friend of ours, who did some watercolors in the beginning, which gave us a first impression,” Vallade states. “Next, I worked with Marion Roussel [character posing/ layout artist] to find a good way to have the most ideal character. We used shapes we had utilized before in other movies to especially push the eyes, which were designed with highlights. One thing that was challenging from the design to animation was the writing process, which was difficult, and we were writing right until the end of the movie and in post-production. I recorded my voice as reference on the animatic with my editor [Ludovic Versace] in order to be able to change words at the end. Juliette Laurent, our Animation Director, did simple mouth movements so we could alter the dialogue if needed.”

Despite the stylization, there was an aspect of realism. “We wanted the eyes to be realistic and have much more detail when we are close to the characters,” Han explains. “The mouth had to be simplified. From the previous movies, we always had these rules of five mouths per expression per angle. The animators had to follow those poses because we spent a lot of time to be accurate on the expression and pose. The animators could animate by reusing those poses as much as possible; that enabled us to control the framing of the characters while they are moving.” Central to the world-building was being authentic to what Japan looked like during the 1960s as well as to the Belgian heritage of Amélie’s family. “We had many Belgian objects in the house because they are expatriates, and there are some posters in the entryway which have exactly the date of that period,” Vallade notes. “Also, the way we worked on the lights in the house, which are subdued and filtered from the outside.” Great care was taken by the other crew members. “We had an amazing work from our Art Director and Co-Screenwriter, Eddine Noël, to make sure that every detail from the vacuum cleaner to the lizard really existed in this Japanese town at that time,” Han observes. “I met a couple from Kobe who saw the movie, and they were amazed by how respectful we were to their town compared to other movies. It was wonderful to hear that, especially from Japanese people.”

“On my student film I worked with solid colors and without outlines. We wanted to go deeper into the narration process but not to reinvent the wheel. We have worked for many years in this way to have the characters, background and light merge together. There is also this motif of color like a wash painting that conveys the sensibility and naivete of a young child’s gaze.”

—Maïlys Vallade, Writer and Director

A dramatic moment occurs in the kitchen while preparing a meal, when Nishio-san explains to Amélie what happened to her during World War II. “That was the hardest part in the book and was more gruesome as well,” Vallade states. “Nishio-san’s place in the house is the kitchen. We wanted to be respectful. We are not Japanese. It’s a difficult story that is being talked about. We wanted to be intimate with the characters and find a good balance of curiosity between Nishio-san and Amélie. We did a lot of work and made many choices about the sound. In the beginning we tried to work with a real bombing and playing with sounds from the real world; however, it was too much. We didn’t need any flashbacks.” The preparations and acts associated with cooking take on a heighten symbolic meaning. “We didn’t want to do something too graphic or minimize the suffering that Nishio-san experienced,” Han explains. “We had to find the right balance. It felt natural for us to tell her story in the kitchen while she is cooking. Every frame and action that is happening illustrate her state of mind; for example, when she pours the rice on the screen and it covers her face illustrates the fact that she was buried. As a fun fact, there was a lot of discussion about when she cuts the fish and the word ‘death’ gets mentioned. People were scared that it would be too violent. I come from an Asian family, and we’re used to cutting fish heads and eyes all the time, so it felt natural to add it.”

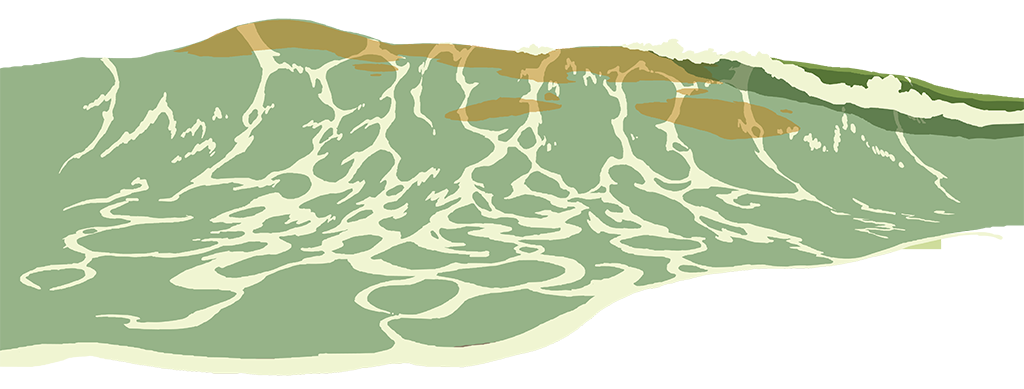

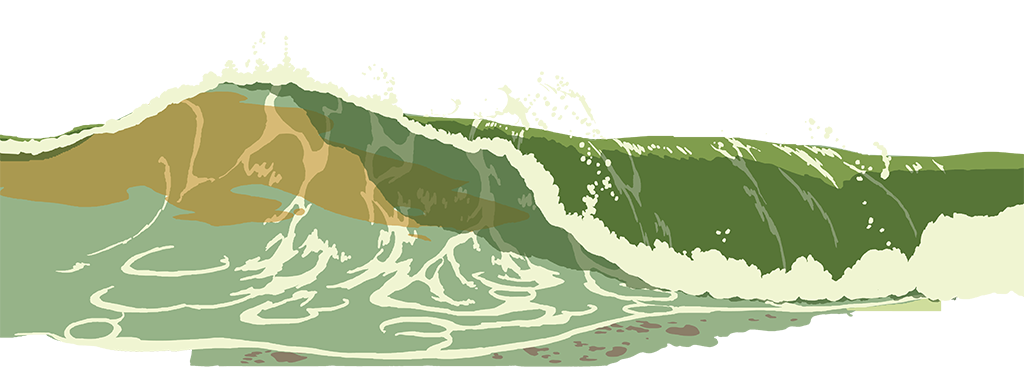

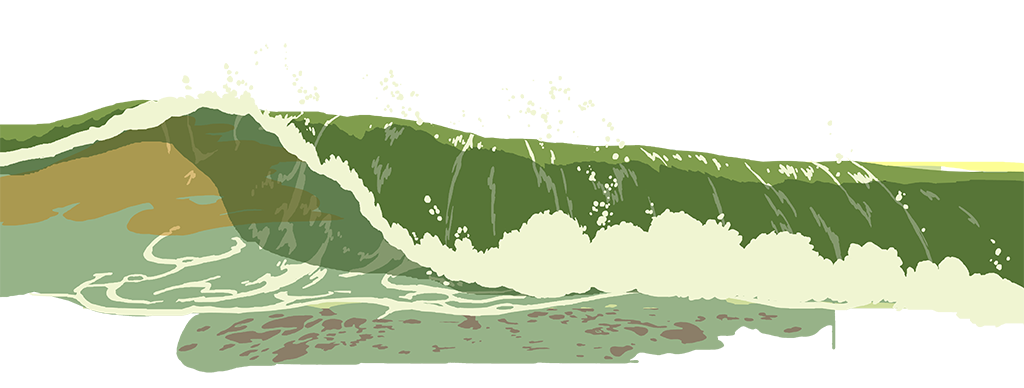

While at the beach with her family, Amélie’s senses get so overloaded that she imagines parting the water like Moses did with the Red Sea. “It was a big question because in the book she walks on the water, but Liane-Cho decided to have this moment like Moses,” Vallade remarks. “It was a good idea because it is a great way for children to see the fish all around them. In the beginning, when we built this sequence, everything was to be animated. but then Liane-Cho said we had to freeze it. And I went, ‘Oh, my god!’” The frozen-in-time effect was accidental. “It was one of the last sequences that we animated,” Han states. “It was nice to time- freeze the waves. In the beginning, the water was supposed to have a lot of effects, and those fish were supposed to move. But we still wanted to be grounded. When the water comes alive, we realized it’s actually because there is a huge difference between the land and waves, which happens a lot of time on beaches. We wanted people to think that maybe everything was in her head. She starts to wake up and ‘poof,’ all of a sudden, the waves breaks and we go back to normal time.”

“From the previous movies, we always had these rules of five mouths per expression per angle. The animators had to follow those poses because we spent a lot of time to be accurate on the expression and pose. The animators could animate by reusing those poses as much as possible; that enabled us to control the framing of the characters while they are moving.”

—Liane-Cho Han, Writer and Director

Tasting Belgian white chocolate was an unforgettable experience for Amélie. “I love Belgian white chocolate, but not my body!” Han laughs. “It is in the book, when the grandmother comes from Belgium and gives this chocolate,” Vallade states. “She unlocks the desire in Amélie, and that pleasure gives her the full capacity of her body.” Body and soul harmonize, resulting in one of several rebirths that occur throughout the story. “It was interesting because it is a grounded moment in the book,” Han remarks. “However, we wanted to push that in an almost abstract way, with the world connecting with her brain. When my kids ate ice cream for the first time, you could see in their eyes the same realization. Kids love sweets. Pleasure guides us to move forward in life and appreciate life.”

Little Amélie or the Character of Rain opens in select theaters on October 31, nationwide on November 7.