By TREVOR HOGG

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Apple TV+, except where noted.

When a security android successfully hacks his protocol programming and gains free will, he has to decide whether or not to hide the accomplishment from the company that made him and his clients. This is the premise of Murderbot conceived by novelist Martha Wells and adapted by Chris and Paul Weitz for Paramount Television Studios and Apple TV+. The sci-fi thriller-comedy consists of 10 episodes that run approximately 22 minutes each and features just under 1,800 visual effects shots by DNEG, FOLKS, Pixomondo, PANC, CBS VFX, Image Engine, Fin Design + Effects, Supervixen and Island VFX.

Prominent storytelling tools are the voice-overs spoken by Murderbot (Alexander Skarsgård) and the UI that reflects his point of view as a SecUnit. “When we were on set, Alex would run some of the voice-overs so we knew what might happen as the shots were being constructed,” remarks Danny McNair, VFX Producer for Murderbot. “We wanted to do something that wasn’t the same as anything you had seen before. We had a lot of conversations back and forth with vendors and each other about how that might reflect onscreen. We’re now becoming more than information. We’re storytelling and pushing the narrative forward with UI sometimes by itself; that was a challenge.”

“We assumed that [Murderbot’s] arm cannons have a dial to them. And a warning blast or ‘you’re dead’ blast! We worked closely with special effects and the prosthetics team to make things we could blow up with blood spray everywhere. We used a lot of that. It was great.”

—Sean Faden, VFX Supervisor

There are shots where computer graphics are overlaid on the entire frame rather than confined to a monitor or tablet. “Sometimes, we did plan, but on other occasions, we didn’t know that a graphic was going to be added,” states Sean Faden, VFX Supervisor on Murderbot. “It happened to be a pensive moment for Alexander Skarsgård. There is a bright background behind him on the left, so we can’t put the graphic there, or something is distracting on the right. We have to treat the plate to make it more receptive to graphics. We did a lot of testing early on. The first thing that sold it for the showrunners was Murderbot being worked on by the repair cubicle and waking up in a fog. We had AR floating graphics, not literally in front of his face because we still wanted to see the actor, but we wanted to bring the audience in as if it feels like something Murderbot is seeing.”

A full body scan was taken of Skarsgård to assist with any digital double work or when Murderbot gets mended by the repair cubicle. “We knew roughly what Sue Chan, our Production Designer, was coming up with for the repair cubicle,” Faden explains. “It had these arc-shaped arms, and off of those had these robotic arms capable of moving in all possible directions. In the end, we only had a chance to show a couple of hero things. We made sure to show that this unit was capable of printing flesh, mechanical parts like tubing, and the structural mesh that holds it all together. There were numerous pieces and a lot of story to tell. The layer cake of Murderbot was based on a torso created by our prosthetic team, who we had on set for a lighting reference and also scanned and photographed. We reverse engineered how all of those pieces could be built in 3D.”

Skarsgård was a willing collaborator. “Alex would say, ‘Tell me what you need,’” McNair recalls. “We painted his skin blue. You don’t always get that, so having an actor willing to be part of the visual effects process was great.” The blue wound had some tracking markers, and the prosthetics team dressed a torn, bloody skin edge. “Trying to track a wound edge is a classic difficulty in visual effects, so having that for real was helpful,” Faden remarks. “The little arm that came off the curved arm of the repair cubicle was fully CG, but the larger curved arm was practical. A guy on another side of the wall with a pulley was moving this thing back and forth, and we had a light on that. The interactive light kicking on Alex’s stomach and torso was helpful because once we matched it in CG, the whole thing tied together.”

Security camera footage was part of the visual language. “Because many times Murderbot would have visual overlays on top of things, it was an interesting way to further the story,” Faden states. “If you were looking at an image of Mensah [Noma Dumezweni], we added the graphics showing this irregular heartbeat. Those sorts of things help the audience understand the shot’s intention. We did a lot of subtle warping and chromatic aberrations. We worked with the colorist on what that final color would look like.” The camera format ranged from GoPros, Sony FX30, DJI drones, ARRI ALEXA LF and [ALEXA] Mini. “Generally, the security camera was the cheaper smaller cameras buried on set,” Faden remarks. “Sometimes, we would have to remove them.”

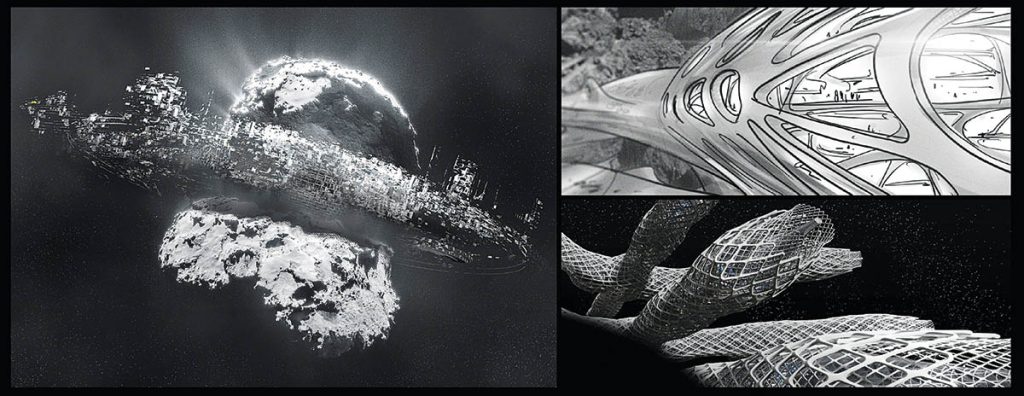

Outer-space establishing shots of Mining Station Aratake and Port FreeCommerce were done in 3D. “If you move the camera too much in space, everything looks small, and the space stations are large,” Faden states. “There is movement. I’m sure there were matte painting enhancements on top and 2.5D projections on some of these shots. We built the massive mesh spire structure seen in the Port FreeCommerce space station; that [structure] was built in 3D because we have it in a few different angles and shots. We went on scouts, took pictures of some universities in Toronto, and did quick Photoshop paint-overs with these large meshes to represent the sky. It was supposed to feel 3D-printed by little flying bots that would create these massive meshes, and the meshes were a part of the spires, and the spires were bored out of these asteroids. People live in buildings built into those spires.”

No atmospherics exist in space. “Because this was based on an asteroid being mined, there’s always some amount of dust close to the surface of this thing, and at the end of every one of the spires, we have an atmosphere exhaust,” Faden explains. “Those allowed us to play with the lighting. We have a lot of small lights within the actual space station. If you look at some of the shots in the final episode, I said to Pixomondo, ‘What if the light is clear at this moment because there’s no atmosphere? Then, as a ship rotates through the dust, you get a flare or atmospheric scattering of the light.’ I had landed at LAX on a particularly foggy night and put my iPhone to the window as our plane was taxiing around the runway. You see all the flashes and light play in the background. There is so much variety in the color of light. We used a lot of that for some of the final shots with the strobe lights you have at an airport.”

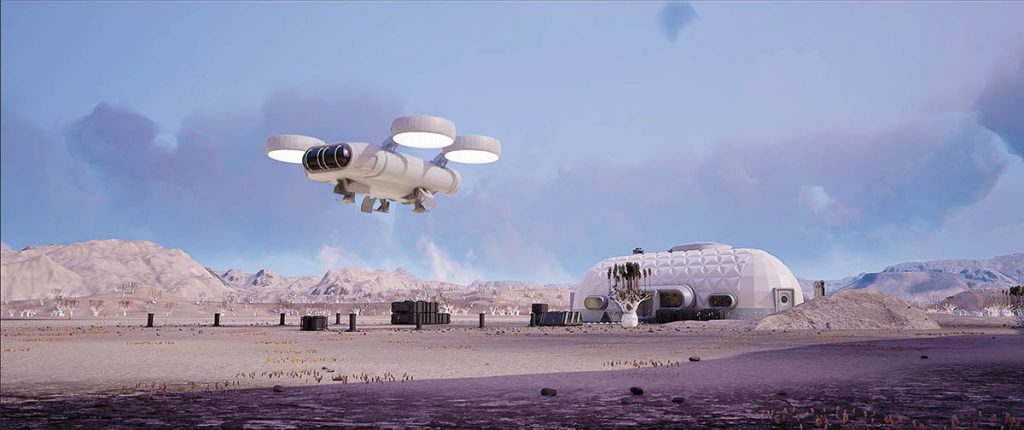

Window shots are plentiful. “The Habitat had a large backdrop, which worked sometimes through the windows,” Faden states. “There were shots where you had to see the full Hopper or more detail through the windows, so we would do a full replacement on those. Because the windows of the Habitat were cloudy by design, you got a sense that there was something out there. The Hopper, however, was a massive LED wall [20 panels by 60 panels]. That footage was mostly based on two days of filming in Utah. I went there with a small crew and shot drone footage in Moab. That location served as the PreservationAux [a scientific research organization that purchases Murderbot] world or anything close to where our heroes were living. We also did the same thing with drones for the areas around Toronto for Episode 103, where they land in the river, and for Episode 106, where they crash-landed.”

“We sent the plates to Fin Design + Effects in Australia to do rapid prototype treatments,” Faden remarks. “They replaced the skies, added planetary rings and introduced some prismatic effects. This planet has colorful clouds, like fire rainbows. We had one to two-minute clips running on the LED walls that worked for us on 90% of the shots. We had a greenscreen on our LED wall for certain things, like the crash and explosion of the beacon in Episode 105. All Sanctuary Moon [a space opera watched by Murderbot] was heavily based in VAD work. We had a 270-degree curved screen.” Clever visual trickery took place on the virtual production stage. “We did something cool,” McNair reveals. “Because some of our scenes were running two minutes [long] and the loops were two minutes, we built cloud transitions so you could bury the loop if the scene happened to go over the length of footage you had. In a couple of cases, it was successful.”

Hostile worms with heads on either end are encountered by PreservationAux while conducting Mining Survey 0Q17Z4Y. Murderbot allows himself to be swallowed to eliminate the threat. “People on the show were like, ‘Can’t this be a CG thing?’” Faden reveals. “We said, ‘We want to see what Alex or a stunt guy is going to do in this moment.’ We mounted a kiddie tunnel with a small crane, so when the crane dropped, so did the tunnel. Once he’s actually in it, we had that same tunnel laying on the ground and grips moving it back and forth; that gave a much more realistic reaction to the stunt performer inside of this moving shape.” Camera equipment was customized for the shot. “Don’t forget the huge 360 rig that we built on the sand to mount a camera so we could get real footage of the spin, which we eventually replaced,” McNair states. “But we had done so many scans and 360 LiDAR of that whole space so we could rebuild it faithfully. Then, having grips swinging around the camera with Alex riding on this huge rig in the middle of a quarry was cool.”

Extensive animation tests were conducted for the worms. “We had some good concept art from Sue Chan, but when you start making it for real and knowing how this thing is going to move, lots of stuff has to be changed,” Faden notes. “We had to find our way to make sure we had a worm that was cool-looking, terrifying, and functional at the right scale for the shots. Then, we started animating it. We began with walk cycles and making sure that there was variation in the legs so they didn’t all feel too even. This thing is heavy, so how does it displace the dirt? Little pebbles get kicked out, and bits of dust and displacement are in the ground. When it’s running and going fast, the worm is churning up a lot more volumetric material that obscures some of the legs. There was a lot of back and forth on that once we got a shot to work. We didn’t want it to look like the worm was floating on the ground or to see a leg digging into the ground because that would have looked fake, too. There was a balance between how much volumetric dust and larger pebbles get kicked out. Even the coloring of the worm itself [was a subject of discussion, as was] putting more aging on the belly or treating the plates as if they grow like fingernails. You might not notice it right away, but it feels organic for a creature like this.”

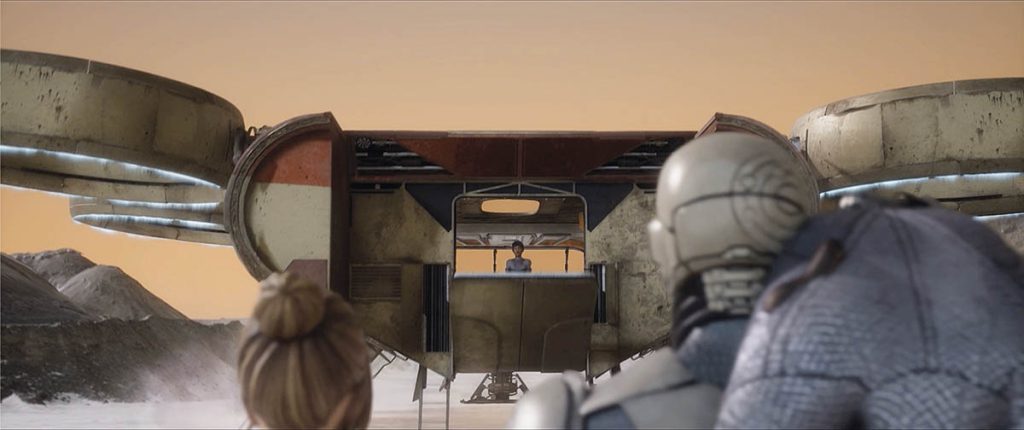

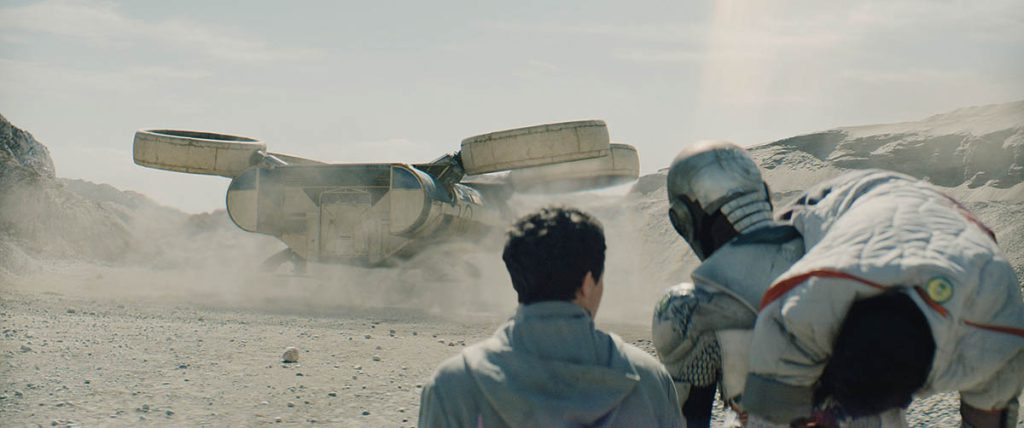

The same flying technology are used in the Hopper and drone. “We figured it was like a Dyson Airblade on steroids. This thing is so strong that it can create such a high-pressure system inside of these hoops that it produces a downward thrust,” Faden states. “Our prop department built a full-scale drone. There are moments where the actors have to handle and walk around with it. That was more straightforward because we could scan and match the drone faithfully. A good-size rear third of the Hopper was built, but the actual turbines were never constructed. There was no front or back landing gear. It was a lot of CG extension work to build those. However, the on-set piece was amazing. We had two Hoppers that hopscotched their way through our different sets because it took too long to take the Hopper apart and rebuild again. We shot extensive footage of the interior of our Hopper, which was a set on airbags so it could still rock and roll around. That was on our stages, and we had an LED wall in front of it. When we looked out the backdoor, that was either greenscreen or, occasionally, we had some backings that worked.”

The helmet of Murderbot posed difficulties. “One of the first things we started to develop was how the helmet could open in a cool way that feels somewhat mechanical,” Faden explains. “We have six or seven shots where the helmet is either opening or closing, which often has a narrative reason; he doesn’t want to talk about ‘this’ anymore or is mad. We would have Alex do his thing, but sometimes it would be decided in post, ‘We want to open the helmet here.’ Or, ‘We want to close the helmet for all of these shots.’ There were a lot of hidden moments that we had to work through to help the edit make sense and make those occasions when he opened a helmet be much more impactful.”

Given that the protagonist calls himself Murderbot, blood and gore are unavoidable. “There is one particular death that we think everyone is going to love because it’s so not what you would expect,” McNair laughs. “Having special effects put blood on the wall, then have blood on the ground that we can pull into, but then making up how his arm cannon would kill a human. I imagine that if Chris Weitz were asked what his favorite death was, he would tell you this is it.” Assumptions were made. “We assumed that the arm cannons have a dial to them,” Faden notes. “And a warning blast or ‘you’re dead’ blast! We worked closely with special effects and the prosthetics team to make things we could blow up with blood spray everywhere. We used a lot of that. It was great.”