By TREVOR HOGG

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Ubisoft Entertainment and Lucasfilm Ltd.

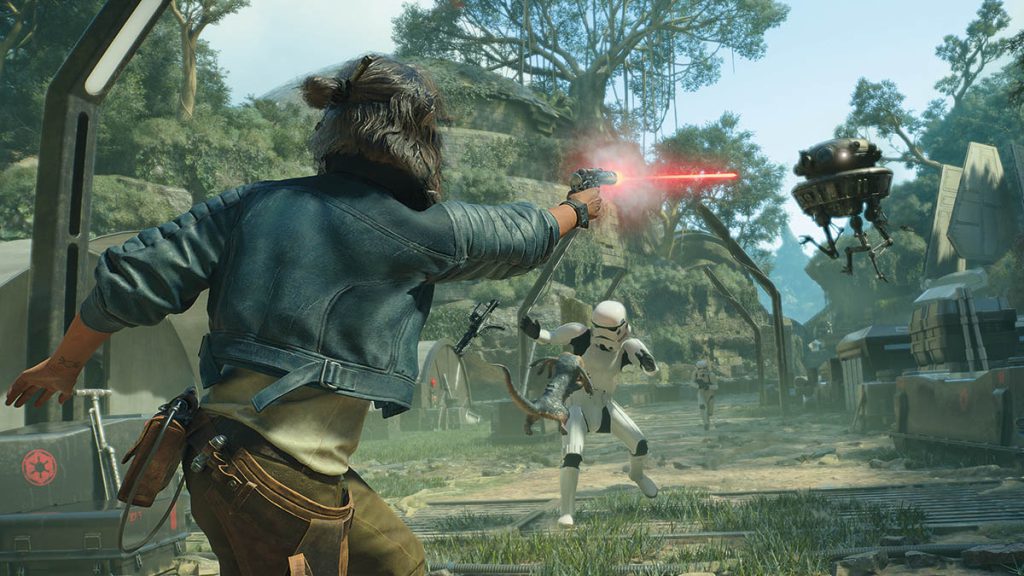

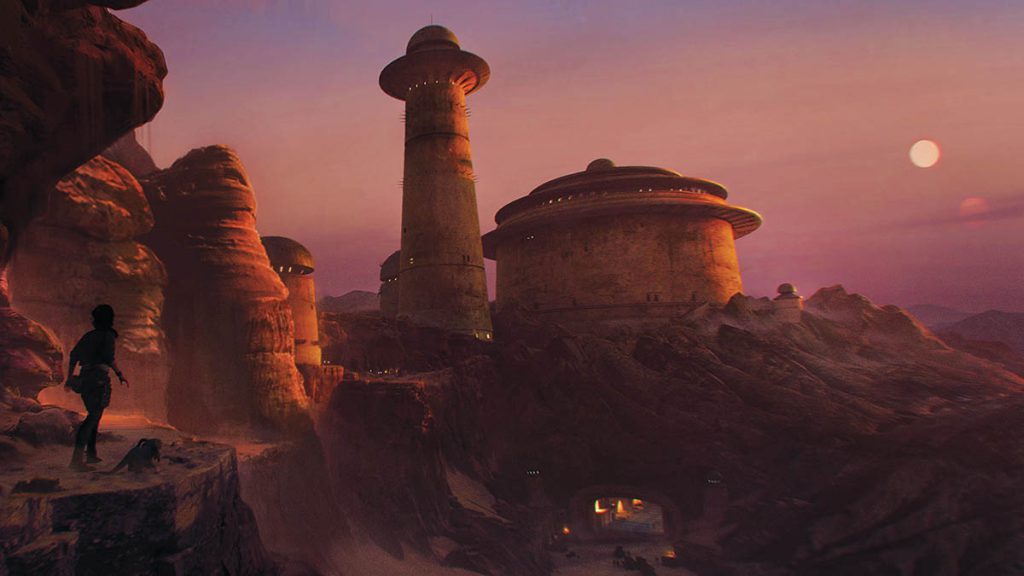

Considered part of the revival of Lucasfilm Games is the first Star Wars open world video game where small-time thief Kay Vess becomes entangled with the Pyke Syndicate, Crimson Dawn, Ashiga Clan and Hutt Cartel. Set between The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, Star Wars Outlaws was published by Ubisoft and developed by Massive Entertainment, which is responsible for the real-time tactical games Ground Control and World in Conflict. The action-adventure revisits familiar faces and places while introducing new planets and characters that expand the scope and understanding of the ruthless criminal underworld. The end result went on to receive the 2025 VES Award for Outstanding Visual Effects in a Real-Time Project, highlighting how visual effects have become an integral part of providing players with an immersive experience.

Even though the story is set in the Star Wars universe, an effort was made not to be self-referential when devising the shape language for the game. “It’s not just to reiterate all of the things that you have seen from Star Wars, but to bring new things into Star Wars,” notes Benedikt Podlesnigg, Art & World Director at Massive Entertainment. “One thing that we tried to avoid doing was only looking at Star Wars reference to create new Star Wars because, in the end, you will never create something new. We looked at what inspired George Lucas, Ralph McQuarrie and Doug Chiang when they created new things. What are they looking at? What is the cultural influence? Using the example of Toshara, we examined what if, instead of making a game, we made a movie. Where would we go and film it? Then, we explored that location and drew inspiration from it. The winds shaped Toshara, so we brought aerodynamics into it, which answered many questions for us. It influenced the shapes and patterns.”

The wind needed to be simulated on Toshara, which raised the complexity. “Normally for a game, you would have one wind vector, which is going to be the direction and strength pointing in a direction,” remarks Stephen Hawes, Technical Art Director at Massive Entertainment. “The biggest challenge was that we changed the wind system in Snowdrop [the in-house game engine], so it’s more the Beaufort system for wind strength. When the art director says, ‘I want strong wind,’ you give him strong wind, and everything is flapping around. ‘That’s too strong. Let’s pull it back.’ But there’s no word to describe or number to put on this. We literally made a weather vane prop that would spin based on the wind, and it would give a read on how windy it was. We had all of the wind settings with a written English term like ‘still’ for no wind and ‘hurricane’ for a violent storm. On the cantina, you have little slats on the windows that move based on wind strength. If the wind strength is too high, they will move too much. It was important that we got that value nailed down with Ben, then tweaked things, like more movement in the grass or less movement on the clouds. That’s an easier distinction to make to get the whole world working. We added a whole different wind track for how the grass moves.”

Ray tracing was an indispensable tool for ensuring lighting continuity. “We used ray tracing to give us quite a bit back in terms of real-time lighting updates,” Hawes explains. “There are many things you can do when the lighting isn’t baked. This allowed us to create interesting set pieces. One of the examples we used as part of our [VES Awards] nomination reel was the collapsing tunnel. You’re escaping a ship that is landlocked, falling apart, and the corridor is slipping vertically while you’re in it. You’re sliding down through it as explosions are going off. There are many moving parts that we can do far more with now to keep the lighting all consistent.” A new environmental experience for Massive Entertainment was going beyond the ozone layer into outer space. “For Snowdrop, one of the big new improvements was how we handled space content, especially the nebulae that we have on Kijimi or Toshara, which is one of the space regions we created that has huge volumetric clouds where you have more or less density,” explains Baptiste Erades, Senior VFX Artist at Massive Entertainment. “This was not something that the engine was meant to be putting the player in, such a big mass of overdraw. We are usually trying not to put the player in this perspective. However, since we are in space, and there are many examples in Star Wars where they have this situation, like in the Kessel Run, we had to create a whole new technology that improved our volumetric system so it can also be used for clouds and such things.”

Having to interact with the various environments are the iconic speeders. “It was a lot of fun, but still challenging because at some point when a speeder gets chased by other speeders, you start to have a lot of visual effects and elements reacting to them,” Erades states. “Performance-wise, this was quite tricky. One of the things that was challenging, especially in the Star Wars universe, is that the speeder floats in the air, so you don’t have any real feedback elements. You don’t have any wind blowing, except for when they start moving. We had to find a way to make them feel real. Usually, in other games, you have the wheel turning fast and white smoke coming out. We had to try to drag some of the ground, depending on whether it was mud or dust, to come out, to make the speeder more anchored, even if it was actually flying. It was the same when you jumped. Depending on how your speeder lands, you will have some dirt spikes coming next to you to emphasize the heavy damage that you can take on top of this huge speed you have. We’re trying to get all these elements in our scene.”

Research was conducted into the design techniques and camera choices that the various filmmakers had made for big-screen installments of the Star Wars franchise. “Once we had that narrative, we treated it as a movie set,” reveals Bogdan Draghici, Realization Director at Massive Entertainment. “When doing the mocap, we recorded all of the cameras, so the camera movements and feel come from cameras being operated by real camera operators. We realized that the imagery for this project would be challenging to achieve with our standard camera tools. We had discussions with Stephen [Hawes] and his department. They created this unique lens project that emulates certain types of cameras and lenses. In our case, the camera we were targeting was the same one used in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. It was Ultra Panavision 70. It’s an anamorphic camera, which comes with a specific set of artifacts and traits. We tried to go as cinematic as possible for each cinematic [shot], not only to support the story but to feel like a small movie.”

Getting the correct visual aesthetic also meant taking a retro approach. “We looked at every reference for characters, clothing or technology from the era when the movie was made,” Podlesnigg remarks. “There were 1960s and1970s technologies that we looked at for the Trailblazer. There are some muscle cars in there. We used a Swedish motorbike as a reference for our speeder. However, even for the characters, Kay Vess’s haircut is inspired by the style seen in the movie. It’s these kinds of references and all of these small things put together that make the aesthetic work. If you take one thing that is too modern or old, it doesn’t work anymore.” An important aspect of the world-building was being true to the setting being depicted. “Toshara is a moon with a solid Amberine core that has a crust on top of it that is slowly being stripped away by the wind,” Podlesnigg states. “Everything was created with that in mind. The wind direction, architecture, harnessing of wind for electricity, the choice of lenses you see in space, the nebula and the dust clouds revolve around this concept. Our world-building team has done a tremendous job hitting all of these small notes.”

Cinematics have different aspects when it comes to complexity. “We have the Barsha standoff where the intensity of the emotions is quite high, and that is to be reflected in the performance,” Draghici states. “Not to mention, compared to film, all of these performances have to be translated to CGI puppets. How can we make this transfer to preserve as much of the actor’s performance as possible? Then we have the Darth Vader scene. Because Sliro Barsha has such a big ego, he displays artifacts collected from conquered gangs and species in a glass case. I wanted to play with reflections on the glass. Sliro Barsha is admiring his collection, and then, in the glass reflection, you see the door opening and Darth Vader comes in. We had to do all the math behind where the character needs to stand, where he needs to look, what point on that glass he needs to look at, how the camera needs to move around the character to make sure that it’s at the perfect moment for when the door opens and Darth Vader is revealed. And there’s the complexity of seamless transitions and keeping the player immersed.”

Devising a hologram system was not easy. “It sounds straightforward, but we had to answer interesting questions, like what if you look at a hologram from top down?” Hawes states. “I’m proud of the results we got. Moreover, it helped with the narrative because if the script changed and this character was no longer on the ship but needed to be talking, how do we do that? The character can be added through a hologram, which allows for the scene to be placed back in. Keeping in mind the era you’re in, the holograms change in terms of aesthetic. Giving the art director the tools to tweak and make the holograms look as they needed, while also ensuring they worked aesthetically, was a big challenge. In the end, the holograms became quite a strong element within the game.” Blaster fire was another interactive light element. “For tracer bullets, you usually boost the intensity for daytime, otherwise you will not see it,” Erades explains. “You have another intensity for night and maybe a third one for when you’re inside a building. Our game is quite difficult because we have multiple planets with different times of day, so it’s hard to know if it’s nighttime or daytime, and you have space with a different sun that has various colors. It was challenging to keep a consistent look for the laser bolt that was not too saturated or luminous but still felt like a powerful effect in all situations without triggering the lens flare.”

Inspired by World War II aerial dogfights, outer space battles are a trademark of Star Wars and something fans would be expecting. “One of the biggest challenges I had with the lighting artists early on was if you look at the planet, the exposure kept changing violently,” Hawes reveals. “We have a different lens for when you’re in space. The exposure is clamped, so it gives you that Star Wars look where you can see the stars and planet, and when you’re firing your blaster and have explosions going off, the exposure in the scene isn’t fluctuating. Then it was making sure from my side that the lens is set up for space hits. It’s going to be different in its thresholds. If you fire a missile, turret or blaster fire, you can’t just flare. We want to have flare for the sun and anything else that is triggered, but everything else should be quite subtle. We have things like asteroids. In some maps, there are thousands of objects all updating. Normally, that is a bad idea to have each object updating, so we came up with a system for doing all of the updates and then doing it all in one pass.”

Open world games are familiar territory for Massive Entertainment. “The biggest difference was that the Tom Clancy’s The Division games we worked on were city-based open world,” Podlesnigg remarks. “Now we’ve added landscapes, space, speeders and spaceships to it. The biggest difference for us was, ‘How do we connect all of it together?’ But with Snowdrop, we have one of the best toolsets on the planet, which is powerful to work with and also fun.” One particular line of dialogue proved to be problematic. “We have the line, which is Kay Vess with ND-5 in the Trailblazer at the end of the mission, and they’re satisfied in accomplishing what they needed to accomplish. ND-5 asks, ‘Where are we going next?’ And her line is, ‘Anywhere we want.’ Believe it or not, we shot over 100 versions of that line to get the proper tone! We had to record that for the announcement trailer and kept sending it to Lucasfilm. People would be like, ‘Maybe here the tone can be different.’ A lot of notes from everybody! I hope that some of the lines we created become as iconic [as ‘I have a bad feeling about this.’].” Working on an established IP was fascinating. “Not everything exists in the movie and you have to extrapolate,” Erades observes. “It was interesting work to have to respect the IP and the vibe of Star Wars, but also make your own version and push it forward.”