By TREVOR HOGG

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Union VFX and Sony/Columbia Pictures.

Partners in crime for over 23 years, filmmaker Danny Boyle, cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle and Union VFX Co-Founder Adam Gascoyne have reunited for 28 Years Later, the third instalment of the zombie franchise established by Boyle and Alex Garland, which continues to explore the downward spiral of humanity as civilization gives way to primeval chaos. “Danny and Anthony aren’t making traditional visual effects-driven films,” notes Adam Gascoyne, Visual Effects Supervisor. “Everything we do has to feel embedded in the photography, very much in the background. That means there’s a huge amount of planning to give them the freedom to shoot organically and focus on performance, without visual effects interfering in that process.”

“The film is intimate, but it has moments of huge cinematic scope. Balancing those, especially across unconventional footage formats, was the real challenge. But it’s what made the project so creatively satisfying.”

—Adam Gascoyne, Visual Effects Supervisor

Serving as points of reference were the first two films. “We went back to 28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later to study the aesthetic and mood, particularly how they handled realism and chaos,” Gascoyne states. “The first film especially had such a gritty, DIY sensibility that we wanted to retain, while expanding the scale. There were early conversations around continuity and where the story might go next, so we tried to lay groundwork visually without limiting future storytelling.” Like the onscreen characters, Boyle is instinctual. “Danny communicates in terms of emotion and rhythm. He’s very instinctual and might not say, ‘I want a 3D fluid simulation here.’ But he’ll say, ‘This needs to feel like a rupture.’ Or, ‘Like a moment of beautiful violence.’ It’s up to us to interpret that visually, and that’s what makes working with him exciting. He gives you the room to be creative, as long as it stays true to the world.”

The Happy Eater and Causeway sequences were heavily planned in the advance. “We used previs for layout, timings, and to coordinate the choreography with stunts and practical effects,” Gascoyne remarks. “For complex effects sequences, like the gas explosion and tidal interaction, postvis helped evolve the final shots while working in parallel with the edit.” Visual research was conducted for a variety of things. “We referenced astrophotography by Dan Monk at Kielder Forest for the Causeway’s night sky, imagining what the world might look like without light pollution for 28 years. We also looked at bioluminescent sea creatures, real-world miasma gas, tidal erosion and disaster zone photography. For digital crowds, we studied riot footage and mass movement behavior to get a sense of uncontrolled chaos.”

Complicating matters was the choice of camera. “The iPhone shoot was one of the biggest technical curveballs,” Gascoyne acknowledges. “We had 20-camera and 10-camera iPhone rigs, some hand-held and some bar-mounted for bullet-time shots. Matching and syncing these in post meant solving issues around chroma subsampling, stabilisation artifacts, clipped highlights and unrecorded focus shifts. Creatively, we had to make a forgotten, devolved world believable. One where nature has reclaimed infrastructure and humanity has gone feral. But it still had to feel intimate and human.” Streamlining the visual effects process was not having to divide the digital augmentation among multiple vendors. “Union VFX, being sole vendor, helped maintain consistency and allowed us to work fluidly across teams in London and Montréal. We built custom tools to handle iPhone media, matchmove multi-cam rigs, and simulate natural phenomena like water and gas. Our pipeline had to be nimble. We had over 950 shots across the film, many of them subtle, and some incredibly complex,” Gascoyne says.

“Danny [Boyle, director] communicates in terms of emotion and rhythm. He’s very instinctual and might not say, ‘I want a 3D fluid simulation here.’ But he’ll say, ‘This needs to feel like a rupture.’ Or, ‘Like a moment of beautiful violence.’ It’s up to us to interpret that visually, and that’s what makes working with him exciting. He gives you the room to be creative, as long as it stays true to the world.”

—Adam Gascoyne, Visual Effects Supervisor

Different stages of Inflected are encountered throughout 28 Years Later. “We worked closely with prosthetics to build a multi-stage progression system, from early infection to full degeneration,” Gascoyne states. “Our role was to augment with subtle eye shifts, facial damage or infection bloom. We kept everything grounded, our job was never to overwrite their excellent work, but to push it further when needed.” Impacting the creation of digital doubles was the prevailing nudity. “There was little to no wardrobe or props to hide behind, so digital doubles had to stand up to full scrutiny,” Gascoyne states. “We developed anatomical shaders with nuanced textures for scars, grime and infection markers that blended cleanly with prosthetics. For crowds, we varied limb damage and posture stages to give a sense of physical deterioration without relying on costume coverage.”

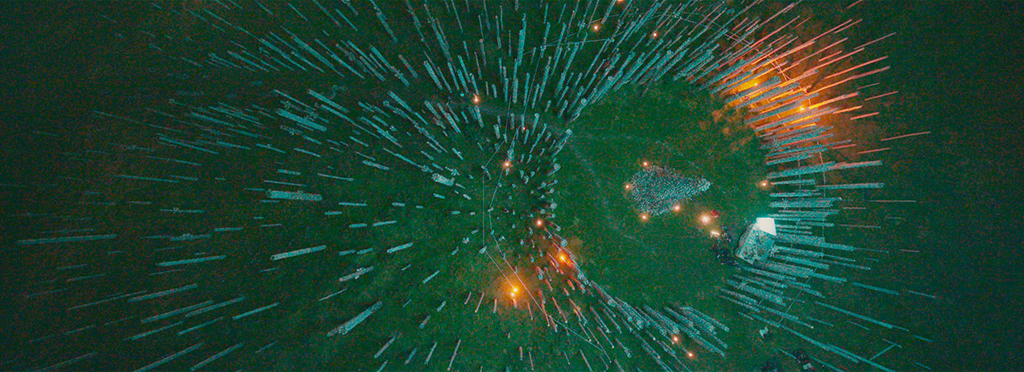

An important aspect of the environmental work was the overgrown vegetation. “The world had to feel like it had been abandoned for decades, so we used procedural vegetation and overgrowth simulations to help show how nature had reclaimed space,” Gascoyne describes. “Sky replacements were frequent and important, particularly in sequences like the Causeway, where the fully CG aurora sky helped give a sense of time passing and nature expanding.” The wildlife was expanded upon. “We used digital deer, rats and occasional digital horses where safety or logistics prevented practical shots. The CG animals were integrated to feel completely part of the world.” Pivotal to the narrative is the isthmus and the tide going in and out. “Only a short water section was available on set, about 100 meters, but the script demanded something that felt 1.5 miles long. We built out the full tidal causeway in CG, including effects-driven water, mist, seaweed and bioluminescent interactions when characters stepped in. The waterline was animated based on real tidal cycle data, and the sky was a full CG aurora nebula with flocks of 10,000 murmuration birds.”

Visual effects collaborated closely with stunts and special effects. “From early prep, we were embedded in conversations with the stunt and special effects teams,” Gascoyne explains. “Our digital enhancements were always designed around what was captured practically, like blood impacts or interaction with the gas cloud. The bullet-time iPhone rig, used for capturing gore in motion, was developed collaboratively with grips, camera and effects teams to preserve performance while enhancing it digitally.” Most of the principal photography was captured on location. “Greenscreen was used only where absolutely necessary, like safety work or high-risk interactions. For instance, in gas cloud scenes or crowd extensions, we often worked from roto and grayscreen due to the iPhone’s limitations with color keying.” The blood and gore had to feel real, not exploitative. “Danny wanted it to hit emotionally, not gratuitously. For example, the CG arrows and their impacts were grounded in realistic physics, but enhanced to show how brutal and sudden violence can feel in that world. Many impacts were practical, but we helped extend the gore in edit or amplify the timing digitally.”

“We referenced astrophotography by Dan Monk at Kielder Forest for the Causeway’s night sky, imagining what the world might look like without light pollution for 28 years. We also looked at bioluminescent sea creatures, real-world miasma gas, tidal erosion and disaster zone photography. For digital crowds, we studied riot footage and mass movement behavior to get a sense of uncontrolled chaos.”

—Adam Gascoyne, Visual Effects Supervisor

Mixing formats from XL1s to GoPros is a trademark of Anthony Dod Mantle. “With iPhones, stabilization artifacts were a concern,” Gascoyne notes. “We couldn’t rely on built-in smoothing, so we disabled it and corrected it manually. The limited dynamic range meant that we had to match clipped whites and edge roll-off in our CG, especially in effects like explosions. Chroma subsampling [4:2:2] meant greenscreen was unreliable, so for larger studio setups we used grayscreen and leaned heavily on roto. Matchmove was complicated by the unrecorded zoom/focus data, but overall, the iPhone footage brought a raw immediacy that worked beautifully with the story.”

The Causeway Chase was the most complex sequence to execute. “It’s 130 shots long, most of which are fully CG. We had to build the entire environment, tidal water, bioluminescence, a vast CG sky and animate 10,000 birds. Everything had to interact – rain, feet in water, light bouncing off surfaces. It’s ambitious, but we’re incredibly proud of how it turned out.” Maintaining realism while embracing scale was the biggest challenge. “The film is intimate, but it has moments of huge cinematic scope,” Gascoyne remarks. “Balancing those, especially across unconventional footage formats, was the real challenge. But it’s what made the project so creatively satisfying.” Gascoyne is looking forward to audience reaction to certain scenes. “The Happy Eater sequence is a favorite. It’s eerie, visually rich and emotionally intense. The CG gas and explosion were tricky, but they pay off. The Causeway Chase, too. Between the sky, the tide and the birds, it’s epic but grounded in emotion.” The production was a unique experience for Gascoyne. “Working on something that felt like both a return and a reinvention was incredibly rewarding. We hope the audience feels the grit and scale of this world and never notices most of what we did.”

Watch a dramatic VFX breakdown video from Union VFX that showcases the creative design work and depth of detail and that bring out all the horror in 28 Years Later.

Click here: https://vimeo.com/1094786468?fl=pl&fe=vl