By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Neon and Remembers.

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Neon and Remembers.

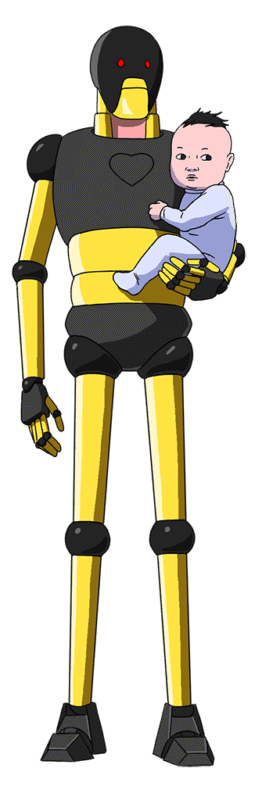

While America and Japan garner the majority of the spotlight when it comes to animation, France has become the third largest producer, with the time-traveling feature film by Ugo Bienvenu benefiting from the country’s supportive infrastructure. Arco revolves around a 10-year-old boy determined to visit the prehistoric age dominated by dinosaurs but instead finds himself in an entirely different era where robots and humans mingle as an environmental disaster is about to occur.

“The movie is about whether the concept of things is more important than the reality of it. The movie has a number of underlying questions about what we’re going through and what is going to happen. … I’m not in a bar talking to friends. I’m trying to speak to humans and strangers. I try to make a movie that asks questions that are interesting enough for [audiences] to think about after seeing the movie and cause them to reflect on what they’re going through in life.”

—Ugo Bienvenu, Producer, Director & Writer, Arco

“Animators would graduate from Gobelins Paris or other schools and go to America to work, but now they want to work in France,” observes Ugo Bienvenu, Producer, director and writer of Arco. “We are lucky because studios have been growing in France, and it’s not even a crazy time for animation in the world. France is still somewhere where there’s room for creativity, and we are lucky to have a good system in France with the CNC [the government agency that supports filmmakers], and that helps young directors grow into movies, short films and music videos. I couldn’t have done this job without the French system and free education. My tuition at Gobelins was so low.”

Bienvenu was a teacher at Gobelins Paris for five years. “Almost all of the team on Arco were old students of mine, people I know how to work with, and they work well together,” Bienvenu states. “In my studio, Remembers, I wanted everybody to admire their neighbor. It was like doing handcraft, couture work. It wasn’t at all about industry. It was about human beings and sharing this adventure together. Every time things were going industrial, we were like, ‘We don’t want it.’ It wasn’t looking good. When you have a company, it’s hard to stick to your ideals. I want my people to have good work conditions and be happy. I don’t want them to come and pay their bills. Animators told me at the beginning, ‘I want to do remote work,’ and I said, ‘No. Come to the studio because it’s not about just doing work for me. It’s about sharing and being in the same space.’ They understood it.”

“I’m an animator on the movie. I did all of the storyboards, a quarter of the animatic and 10% of the backgrounds. I did all of the main backgrounds and compositing. … The movies that formed me were done by people who had their studio and were animators themselves, not just directors. The best examples are Hayao Miyazaki and Walt Disney. If we want to be free and use resources in a good way, we have to know all the jobs of the industry and the craft. That’s what I did on Arco.”

—Ugo Bienvenu, Producer, Director & Writer, Arco

A prevailing question for the production was whether the pipeline for short films could be scaled up for a feature film. “We do clear animatics that are 24 frames per second in France,” Bienvenu remarks. “In America, it’s 30. We were animating the animatic at eight images per second, which is a high frame rate for an animatic. Four of us worked on the animatic; me and three of my best people. When it was hard to finance the movie based on the script and my storyboards, my partner and I said, ‘Let’s do what we do in commercials, short movies and music videos. Let’s do a clear animatic.’ That’s what we did, and financed the movie based on that animatic. Because every problem was solved making this animatic with just three people and a small amount of money, everything was so clear that it took us one year and two months to do all of the movie with 150 people drawing. We didn’t know if the process we had before on short forms was going to work that well on long forms, but it did.”

No other studios were involved with the animation. “I didn’t want to co-produce with Belgium or Luxembourg,” Bienvenu reveals. “Everybody in France was telling me it’s impossible. I said, ‘Let’s not use this million that we don’t need [from Belgium], and we’re going to save it by doing everything at the same place. The movie was about ecology, nature and saving our world, and all of this energy spent on traveling – I receive 700 emails per day. It’s too much. I wanted to be with my people. Every day. I was passing through the studio and seeing every animator and background designer. When they were taking a bad direction, I knew it right away; I was taking their chair and redoing it myself straight away so there was no time loss. I’m an animator on the movie. I did all of the storyboards, a quarter of the animatic and 10% of the backgrounds. I did all of the main backgrounds and compositing. This is the European way of working because we don’t have much money. Also, the movies that formed me were done by people who had their studio and were animators themselves, not just directors. The best examples are Hayao Miyazaki and Walt Disney. If we want to be free and use resources in a good way, we have to know all the jobs of the industry and the craft. That’s what I did on Arco.”

Everything starts by making an observation of reality. “I had done a comic book that was a bestseller in France. I even had American companies that wanted me to adapt this book. That gave me the idea that it was possible to make a feature film. But cinema is dying from adaptations and sequels of everything. I wanted to propose something that’s made for cinema and not try to make something else fit in cinema. Then there was a movement in France called the ‘gilet jaunes’ [Yellow Vest], and they were saying all the time, ‘We want things to change.’ I lived in two countries during a civil war, Chad and Guatemala. It’s weird because us Europeans and Western people have forgotten what change costs. Change costs a lot. I wanted to say that. The third aspect is that I’m a science fiction writer. It was COVID-19 at the time, 2020. Maybe the shape of the world we’re living right now is because science fiction just spread bad ideas and possibilities for the future. Maybe it’s our job as science fiction writers right now to imagine the best in order for it to happen. If we want better things to happen, we have to imagine them first. As storytellers, it’s easier to imagine the worst because it’s easier to do drama with dramatic things, and dramatizing good things is hard. I wanted to bring light to the world, and it’s too easy to criticize.”

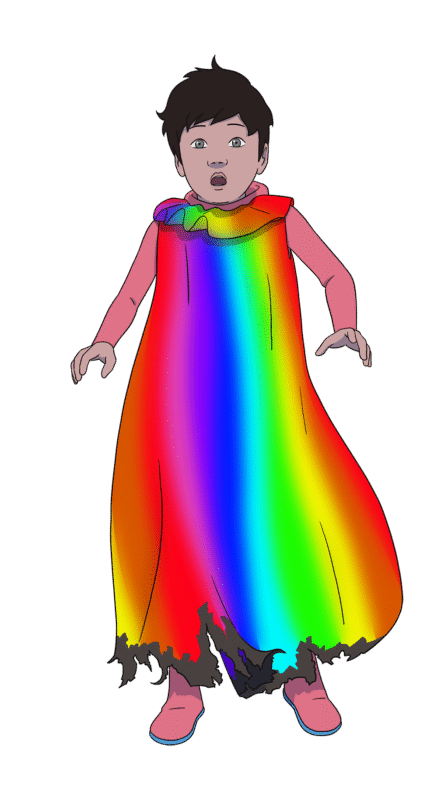

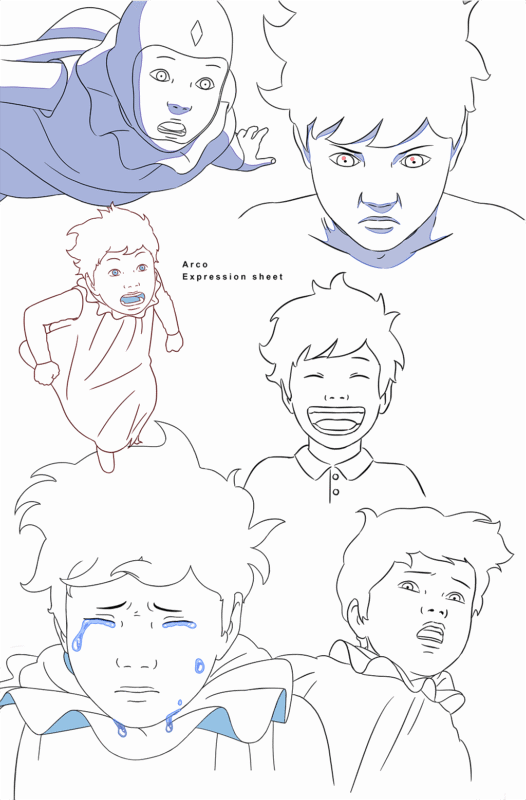

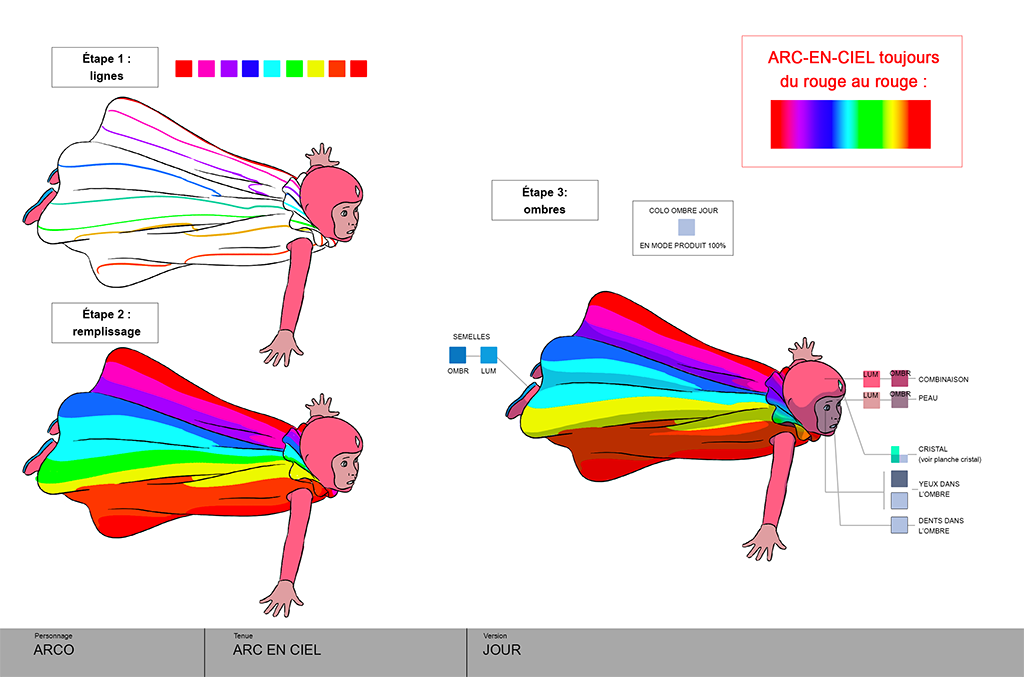

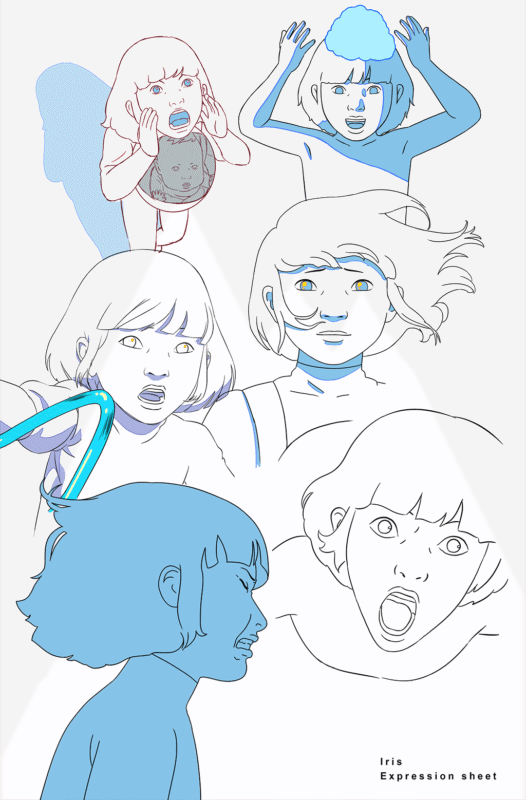

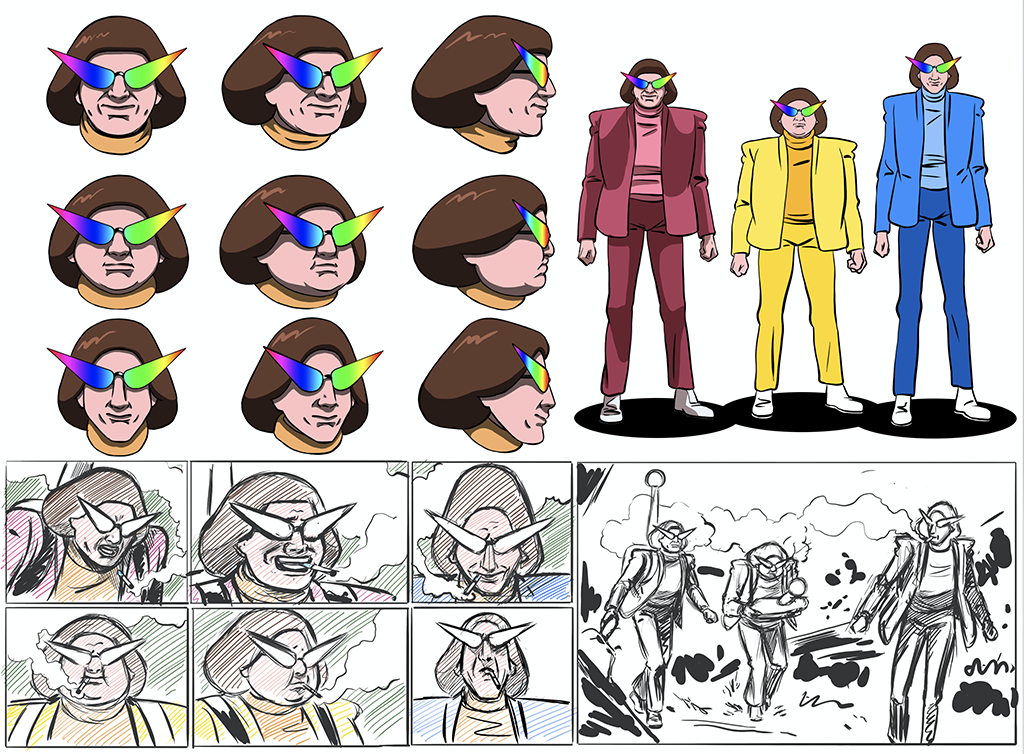

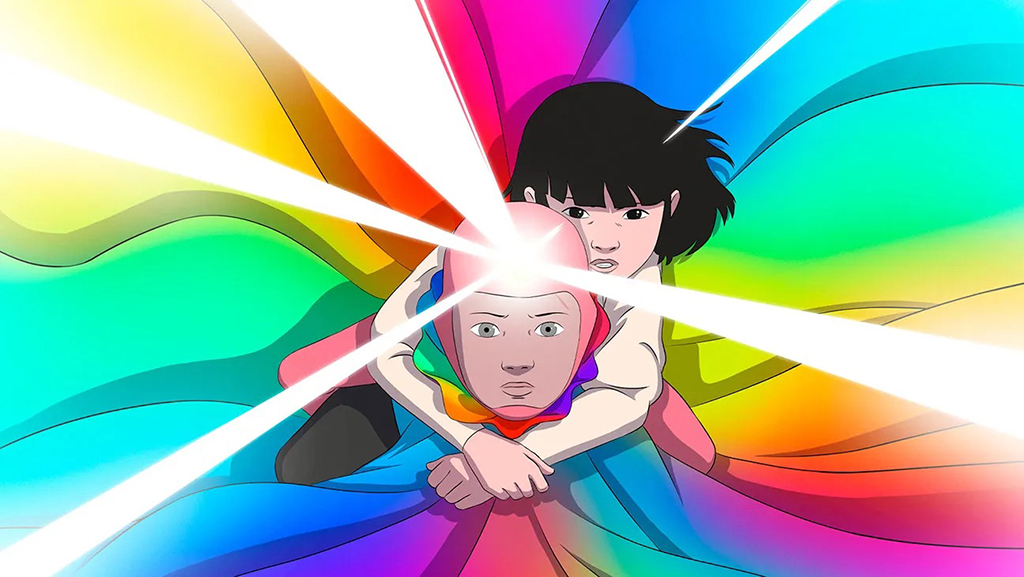

Rainbows are a visual motif throughout Arco. “Rainbows have been in my work since I was 18,” Bienvenu reflects. “I don’t know why. It’s a signature in my work. I have a few signatures such as glasses, robots, rainbows and nature. The core of my work is about transmission. Do we leave the world better than what it was when we arrived? How do we make things easier for the next generation? This is everything I’m thinking about in my life. Arco is the alchemy of it. We always say, ‘It’s the job of our kids to create a better world.’ But I was like, ‘I’m going to try with my tools, everything I have, and my work to put my first stone on this new path. A lot of my work is subconscious, so all of these ideas and thoughts someday magically appeared as a metaphor. The metaphor of all of these concepts was embodied by Arco and Iris. When I found this head coming out of the rainbow, immediately the story came to me. I sent the drawing to my partner at Remembers and told him, ‘I have this character and he’s going to fall in our era, and he meets this girl who helps him go back to his era. In one second, a few years of reflection came together. That was it.”

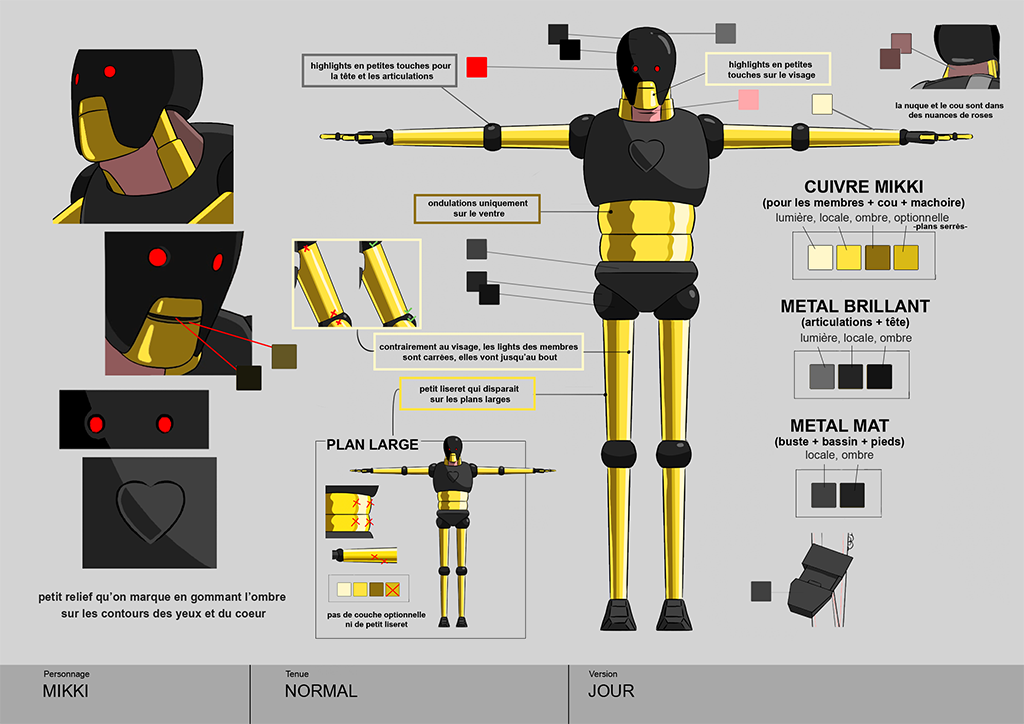

2D was the preferred animation style. “Sometimes, we used 3D animation as a basis, but we re-drew everything in 2D,” Bienvenu states. “I’m an illustrator and have worked with the main luxury houses like Chanel. I draw my comic books. The style of Arco is my style. I didn’t have to search for it because it’s my work. I have lived in a lot of countries and cultures. My style is a mix of everything I went through. Jumanji, Casper, Dragon Ball Z and Miyazaki are parts of me, but the other parts are my observations of the world. It’s the first time in 15 years that people are saying Miyazaki; before, they were saying Moebius, which is weird because I never read him. I was more a fan of Blueberry when he collaborated with Jean-Michel Charlier. I’m a huge reader. I’ve been influenced by so many things. If you’re a creator, you have to read a lot. What matters to me is doing things that come from me but can speak to a larger audience. If we want to touch a lot of people, we have to be so precise on the feelings and emotions. To be able to be emotional, you have to be precise on your own life and observations of the world.”

“Sometimes, we used 3D animation as a basis, but we re-drew everything in 2D. I’m an illustrator and have worked with the main luxury houses like Chanel. I draw my comic books. The style of Arco is my style. I didn’t have to search for it because it’s my work. I have lived in a lot of countries and cultures. My style is a mix of everything I went through. Jumanji, Casper, Dragon Ball Z and Miyazaki are parts of me, but the other parts are my observations of the world.”

—Ugo Bienvenu, Producer, Director & Writer, Arco

Children can handle serious themes. “I want to look at kids in the eyes and trust their intelligence,” Bienvenu remarks. “Kids are clever and know when we lie to them.” Time is precious. “Parents say, ‘It goes so fast.’ But kids don’t realize that. I wanted to make kids realize this heavy thing that life is goes so fast. You have to enjoy the time we have together. Iris doesn’t live with her family, and Arco lives with his family. None of the two positions are easy. Arco runs away, which has consequences because everything we do has consequences in life. It was important to say that if we want things to change, we have to act because our actions will have consequences. We have to choose which consequences we want to have. The danger of our era is indifference to the world we’re living in. I know something about the trees in Japan, but I don’t even know the name of the tree in my garden. Images are replacing presence. The movie is about whether the concept of things is more important than the reality of it. The movie has a number of underlying questions about what we’re going through and what is going to happen. Every society has a different morality, way of living, thinking and talking. My work is to analyze and ask, ‘Are we okay going there? I try not to give my point of view because I hate people that give their own point of view. I’m not in a bar talking to friends. I’m trying to speak to humans and strangers. What I try to do is to do a movie that asks questions that are interesting enough for [audiences] to think about after seeing the movie and cause them to reflect on what they’re going through in life.”

The production of Arco brings to mind a quote from a famous French philosopher and writer. “Voltaire said, ‘There are so many things you have to ignore in order to act,” Bienvenu observes. “This is damn true. If I knew everything I had to do during this movie, I would have never done it, which would have been a disaster. I’m so happy I finally did it. Maybe this is something important to say to the new generation. The bigger the effort is, the bigger the happiness comes from it. Effort is just deferred happiness. It builds you, makes you stronger and makes you a better human being.”