By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Tim Sweeney and Epic Games.

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Tim Sweeney and Epic Games.

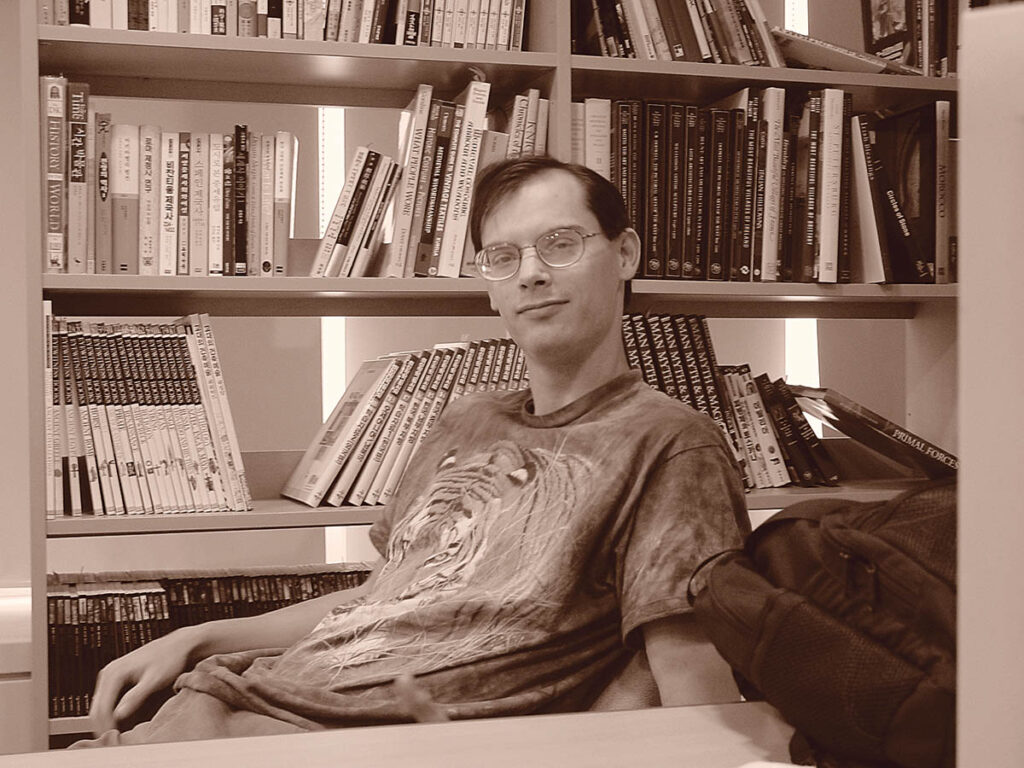

A narrative trademark of the Amblin Entertainment movies from the 1980s was a group of adolescences riding around town on bikes toward their next adventure. Such was the childhood of Tim Sweeney in Potomac, Maryland, who would go on to establish Epic Games, leading him to receive an Honorary VES Award and gain a reputation for environmental philanthropy by buying large swathes of North Carolina forest for preservation.

“My generation had massive individual freedom,” recalls Tim Sweeney, Founder and CEO of Epic Games. “The mothers of the neighborhood would give us breakfast and say, ‘Be back by dark.’ We would go and roam. You might find us 10 miles away on our bikes exploring some woods. There were a lot of adventures and things going on all of the time. I was in a nerd family. My father was a cartographer and made maps for the government but also did printing. My older brother, Steve, was 16 years older, a serious electronics enthusiast and a professional in the hardware business; he always had massive amounts of old and scrapped computing hardware lying around. We would go to junk auctions and buy computers from the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s, and set up a basement full of awesome computer pieces from ages ago. We tried to build goofy things out of them. We constructed go-karts and drove them around the neighborhood. My friends and I were always creating.”

“Nobody in the world has succeeded yet in building a single UI that scales from the most complex usage cases to the simplest one. This is a point where the industry is far from mature, but I can envision that this problem is going to be solved over the next five years.”

—Tim Sweeney, Founder & CEO, Epic Games

Artistry goes beyond the paintbrush and pencil. “Generally, when programmers are writing new systems and games from scratch, it is a creative thing that doesn’t require a skill in drawing,” Sweeney notes. “I remember my first year of programming with nearly perfect recollection. Everything that I got hung up on and learned a solution to is burnt into my brain and constantly influences what are problems with software that make it unintuitive, and how do you improve on that? When you learn to program and learn about ‘goto’ and ‘gosub,’ you quickly realize that the computer is capable of doing anything, if you could only figure out the instructions to tell it to do that thing. I looked at lot of early games on the Apple II and what they were doing. They were easy to see. I can do that. I just need to put the pixels in the right place and optimize the code enough to make it run a performance.” Video games were not the only focus. “I was also programming communication software. Figuring out how to get computers talking with each other and how to scale them to interesting systems to implement games or other types of interactive systems. That experience of using software and figuring out how it’s doing what it’s doing was the key to all of Epic’s early growth and breakthrough.”

While the arrival of Wolfenstein 3D was amazing, Doom was revolutionary. “I gave up on programming for nine months because it was absolutely not clear looking at the screen what Doom was actually doing to make that experience possible,” Sweeney recalls. “But then Michael Abrash wrote some articles about 3D graphics and texture mapping. I had all of these notes. One of the early engine programmers showed me some of the tricks for how to do 3D, and I went, ‘Maybe I can do that.’ That’s how Unreal Engine started. Before Unreal Engine, Epic was a company with a whole lot of small developers working independently contracting with us to build cool games around the world. There was Cliff Bleszinski working on Jazz Jackrabbit with Arjan Brussee, James Schmalz working on Epic Pinball and other games. We realized after Doom had come out that we needed to move into 3D and figure out how to build a game in that space. We took the best people from these small teams and put them together into a big team and starting building on the content, levels and tools for Unreal Engine. I got tasked with writing the editor for this 3D project because I had some spare time.”

“Every industry that needs a 3D engine has a choice of several,” Sweeney notes. “There’s Unreal Engine, Unity 3D, Coda and some proprietary solutions. Our goal is to serve every industry that has a need for high-quality computer graphics. If you need computer graphics and don’t care about quality, there are cheaper ways to do it than Unreal Engine. We’re trying to serve everybody who has high-end needs and be the best solution for them all. This doesn’t mean building vast business empires around vertical industries. For example, almost every studio doing virtual production at scale is doing it with Unreal Engine with great success. We have small teams supporting virtual production because what virtual production mostly needs is an awesome engine. Then they need some features to interface with their funky camera hardware and other on-set devices, but mostly they need an awesome engine. You have to look at the question of ‘Is this engine going to focus on this industry?’ as if you’re asking a question about Linux. Is Linux going to serve the medical industry? Of course, because it’s the best operating system.”

Machine learning and artificial intelligence will make computer programming even better. “Of course, there’s always going to be curmudgeons who don’t like the new way and prefer the old way,” Sweeney remarks. “In the early days of computing, the way to tell it was machine language code and hexadecimal; that was painful but people could do it. Then the way became to write programs and high-level language like C++ or Java or C#. It was a whole lot nicer but still a lot of manual work and you figuring out everything for yourself. The way to make a computer do the thing you want now is for an increasing number of people in an increasing number of fields to tell it what you want in English and have it produce something like that and refine it over time. It’s a better way to work. It puts more power at people’s fingertips for the problems that AI can solve. That’s not for every problem in the world right now, far from it. But it will increase over time, so it’s probably everything or at least close to it.”

“There are several arcs to the evolution of software,” Sweeney observes. “One is the evolution of engines from the big pixels on the screen to being able to achieve absolute photorealism or stylized perfection that you might see in a Pixar movie. We’re close to the end of that, with the exception of human animation, motion and precise face details. Nanite and Lumen are near to real-world, and you can imagine that we’re a few years and steps away from having absolute photorealism for everything. The other arc is content developer productivity. How can you build something that meets your vision? That’s much more important because if you can build something for 100 times less cost, then the process of developing games and movies becomes vastly simpler. AI, more than anything else, is going to create an absolute revolution in that area, and the human effort to be able to create a thing is going to go down by probably by two orders of magnitude. This is the prompt, and the image is finished, or prompts to game. It’s going to happen probably within this decade and revolutionize that. Another facet of the system is the power of the system to create large-scale social multiplayer simulations, and that’s an area it doesn’t look like AI is going to be able to help us. People play Fortnite or Roblox, and you have many millions of concurrent users, but they’re all playing in these little 50 or 100 players sessions because that’s all we can fit onto a server. An entirely new arc of technology development must happen there. It’s too much of a larger-scale simulation that needs to work while respecting all of the other properties, like photorealism, high performance and ease of content creation and programming.”

Remaining elusive is the perfect user interface. “Nobody in the world has succeeded yet in building a single UI that scales from the most complex usage cases to the simplest one,” Sweeney states. “This is a point where the industry is far from mature, but I can envision that this problem is going to be solved over the next five years. I can imagine a word processor with all of the power of Microsoft Word but with the ease of Google Docs. What you don’t want are 1,000 different sliders on the screen. What you really want is a single piece of software in which customized, more advance pieces can be pulled up on demand and are not getting in your way and staring you in the face when you don’t need them. What you really want is the ability of AI to prompt anything to do the complex parts for you and do a good job of it as a way of getting it to at least to a natural starting point that you can go and tweak. Just imagine how much easier it would be to learn Unreal Engine if it had five buttons on the screen and a prompt. You could start prompting it. If you don’t like what you get then you can take what’s given to you, click on and zoom in on objects, and use prompting and actual hand editing to refine things from there. You would find the average person being able to get up to speed 10 times faster and being able to do 10 times more.”

Tech monopolies are stifling technological innovation. “We’re in an especially dysfunctional point in human history,” Sweeney believes. “Governments have allowed unchecked tech monopolies to shut down the normal competitive process of entire industries by enabling whomever controls an operating system to then have a monopoly; even if they want another operating system or hardware purely for merit to then impose a non-merit-based monopoly on app distribution and payments. To use that monopoly to extract far aberrant rents from all commercial activity on the system, like 30% app store fees, and also impose self-cross-referencing regimes that make it hard for other companies to compete with that company’s services. Even if they’re Spotify competing with Apple Music, it’s really hard. Apple has the worst AI in the industry right now, and you would think that it would be no problem. OpenAI should be able to create their own phone AI to replace the Siri on the iPhone, and now you have a vastly better AI, or Brox. AI should be able to do it, or Perplexity or Anthropic. But ‘there can be no other AI than our AI.’ The dystopian world of the moment will end, partly because it’s intolerable for legal and regulatory reasons, and partly because it doesn’t work. The world would be a lot more vibrant and profitable for Apple and Google if they were to let all app and game developers compete on their merits and get out of the way, and instead compete on providing services that developers could choose to use of their own free will by having the best default payment method, browser, search engine and AI assistant.”

Epic Games is hitting its stride. “I don’t have decades more of driving the industry forward,” Sweeney reflects. “I’m 55, so at this age you have to say, ‘God willing!’ Because it’s not assured. We’re starting to get into the primetime of the entire real-time 3D creative industries, everything from film and television production and visual effects to gaming. The most exciting and interesting times are ahead. During this year we’re seeing AI disrupt everything, and people are worried about that. But remember the last time we had a disruption of this scale was when we went from doing everything with on-set models and pyrotechnic explosions to actually moving to computer graphics. It’s always stressful to navigate these changing times.”

The predicted convergence of the film and video game industries has finally occurred. “You’re seeing film production using the same exact tools and assets as video game production. Content is migrating from film sets to video games and vice versa. The process of creating the tools is getting better and more interconnected. We’re heading toward a world over the remainder of the decade where any creative work or intellectual property that is suitable exists both in gamers’ repertoire of what they play and the linear world of watching a pre-made experience. It’s an opportunity for everybody that is much greater as a result of these two industries crossing over like this, and it’s awesome to be at the center of it.”