By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Lionsgate.

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Lionsgate.

Upping the ante of AI drones gone amok in Angel Has Fallen are the fragments of the Clarke Comet that has created a Saturn-like ring around the Earth, which has a habit of breaking up, falling out of orbit and unleashing meteor showers on the inhabitants below in Greenland 2: Migration. “When I read the original script for the first movie, Greenland, that was all about a comet coming towards Earth and how the original extinction event happened,” explains Ric Roman Waugh, Producer and Director. “I didn’t want a movie or an experience for the audience where you were waiting for something to happen. Marc Massicotte, my Visual Effects Supervisor, and I did a lot of research into the real historical and mythology of how these things take place. We found out that actually a lot of meteors and asteroids are made up of ice and different things out in space; they hit each other and start becoming bumper cars. They begin to break up into multiple fragments. A lot of times you’ll see trails of them where there could be millions of them going for miles and miles. We thought, ‘There you go.’ If you actually have a cluster of fragments coming towards the Earth, now you can pelt it at any given time, especially on the Earth’s rotation. Suddenly, you’ve got a monster that can hit you at any given moment versus waiting for the inevitable one.”

Special and visual effects collaborated on executing the meteor showers. “On almost all of these dramatic action scenes we’ve always worked with Terry Glass’s special effects team and ourselves,” states Marc Massicotte, Visual Effects Supervisor. “All of the flying meteors are CG while the center hero hits were pyro. The vehicle flipping upside down was live, then we dressed everything around that. The trees and atmospherics were all visual effects as well as the surrounding scarring and post-impacts. Many departments had to work together to produce the destruction of the bunker in Greenland. “Production design, special effects, visual effects and the cinematographer – those four are crucial,” Waugh notes. “When beginning scouting, we started talking about, ‘What is going to be practical? What are we going to build? What are we going to set design? Where is visual effects going to take over? How is special effects going to blend it with smoke or explosions or whatever it may be? Now, luckily, Terry Glass, who’s our Special Effects Supervisor, and Marc Massicotte, both worked with me on Angel Has Fallen. When we did the drone attack on the lake, we knew what was going to be visual effects and practical effects with huge explosions, blowing up boats, and all of the different things that we did. Then there were the things we would have to augment in visual effects. Because of our history together, everything is a second-hand language in how we operate. It made this a much easier process for us not have to learn about each other, but talking creatively of how we were going to blend all of our different resources together.”

“On the first film, we were always striving to be as close to reality and what the possibility of such an event would look like, the impact of it, It was more about the family and survival than it was about the comet itself. … Going into the second one, the post-impact, we have new worlds we can create and expand onto what has happened and how this would look like. We had more of a carte blanche. The canvas was more wide open for us to create from there.”

—Marc Massicotte, Visual Effects Supervisor

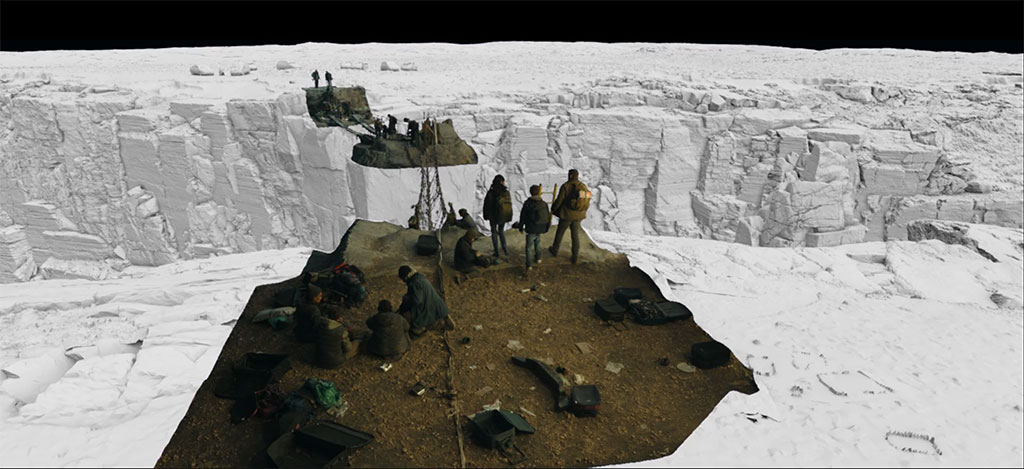

Principal photography took place in the U.K. and Iceland. “We shot in Iceland for Greenland,” Massicotte states. “Then when we land into the U.K., we definitely played the U.K. But we also shot some parts in the U.K. that were playing for Greenland. It was a mixed bag. Iceland played for multiple locations, also France at the end when they get to the crater. The U.K. also played sections of France when we were in the woods. Basically, a forest is a forest and a mountainside is a mountainside that can play for a crater. We extend and build on top of that to get what it is that we’re trying to project.” Retained from Greenland was the visual language. “On the first film, we were always striving to be as close to reality and what the possibility of such an event would look like, the impact of it,” Massicotte remarks. “It was more about the family and survival than it was about the comet itself. When we did see some visuals, we stuck as much to being scientifically based and grounded; we were able to find online reference, like real meteoroids captured on camera. We would go with that and then give it a dash of spice to enhance and make it more dramatic. Going into the second one, the post-impact, we have new worlds we can create and expand onto what has happened and how this would look. We had more of a carte blanche. The canvas was more wide open for us to create from there.”

Starting things off is a radioactive storm. “That one was fun because we’re able to create something that doesn’t necessarily exist but is definitely rooted in reality,” Massicotte explains. “You could find it around the Earth at the moment. For instance, you take a big storm as you would normally know them, then we’d expand on to the scale of it. Then we take electric storms and expand on how that looks. Then we got inspired with volcanoes. There are some volcano eruptions where you would see lightning storms around the eruption. We got inspired with that as well and and with their colors. We just grabbed elements from everything you could find around nature, then combined them all together to make something a lot more dramatic.” Between 400 and 500 visual effects shots were produced by Pixomondo, Hybride Technologies, Crafty Apes and Alchemy 24 over a period of four to five months. “The big scenes were definitely quite challenging to deal with in terms of scale,” Massicotte states. “The scale was always the big challenge because every time you’re thinking, ‘This is going to be big enough.’ In the end, it’s not. The director wants bigger, and then more. You always have to amp the scale of everything. The storm had to be much bigger. For the impacts for the forest sequence we had a big setup, and then it was like, ‘Nope, much bigger. The sky has to be completely covered.’ Initially, it was more isolated.”

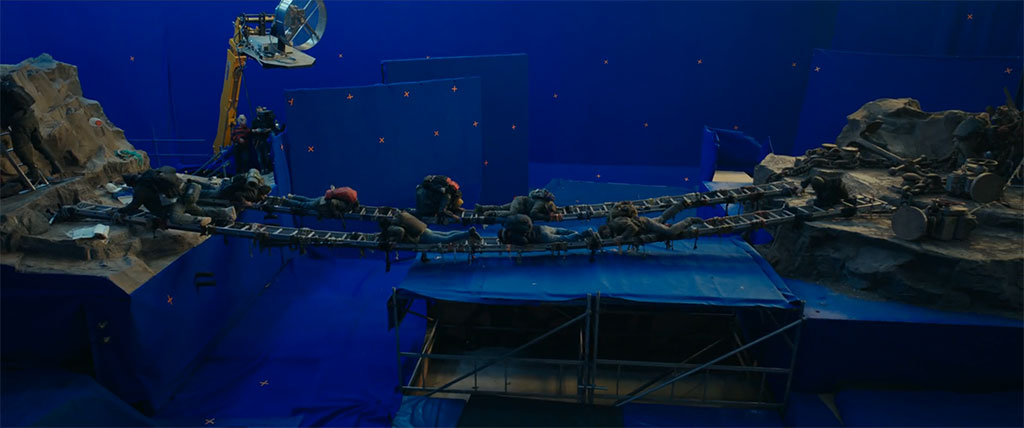

Getting a dramatic reimagining is the English Channel, which becomes a crevasse rather than a body of water. “It was interesting [solving the challenge of] how do you get them across what used to be a water mass when you’ve already sent them across water?” Waugh notes. “Then you start taking the license of when tectonic plates move and fissures happen. The interesting thing was when we were in Iceland filming the opening of the movie, when you see Frank Garrity [Gerard Butler] coming across a molten lava field – that’s the real lava field that was breaking off in Iceland at the time we were shooting. We actually filmed the real one. You see how the earth will just open up – that’s where water can go. That’s how we can create a dry lakebed and have where the water is now miles below the surface because of a new Grand Canyon fissure that comes across it. It’s finding how real world things can happen. Ours are larger than life. Then to create spectacular sequences out of that.” The crossing of the English Channel was captured on a soundstage. “We built everything they would touch,” Massicotte states. “All the ropes and the islands they would land on, from the English side to the center island to the French side. We had massive V8 machines for wind machines in there. We always had to work with the soundstage dimensions we had to expand upon. We finished our crevasse by shooting the area in Iceland that would play for the bottom of that Channel.”

“When we were in Iceland filming the opening of the movie, when you see Frank Garrity [Gerard Butler] coming across a molten lava field – that’s the real lava field that was breaking off in Iceland at the time we were shooting. We actually filmed the real one. You see how the earth will just open up – that’s where water can go. That’s how we can create a dry lakebed and have where the water is now miles below the surface because of a new Grand Canyon fissure that comes across it. It’s finding how real world things can happen. Ours are larger than life.”

—Ric Roman Waugh, Producer & Director

Considered to be a Garden of Eden is the impact crater caused by the Clarke Comet. “That is based on, I won’t call it scientific fact, but scientific hypothesis that there’s a lot of people who believe that the Earth first rebounded after our last major extinction event in the crater itself,” Waugh explains. “Because what happened was it busted so much of the sediment out that you had all the natural minerals and things that would rebound the Earth. Also, because of its depth; we saw this in Iceland constantly. You drive five miles in Iceland and you’re in a completely different microclimate because of the way the mountains protect one another and the different valleys. That’s what we started playing with. The first major crater was just off the peninsula of the Yucatán, and that became its own microclimate, which is what started to rebound the Earth. You use real theory and use it also to give your heroes a destination. What better irony than the actual thing that devastated you is the thing that’s going to bring you back!?”

Major sequences get broken down into smaller sections and details to figure out how to create different areas of devastation. “Did bigger pieces hit and create huge valleys that are craters?” Waugh asks. “You start breaking down the physics of what happened. Then you can start coming up with the creative or what you’re trying to get to. For example, the English Channel. We wanted to have a sequence of, ‘What if you came across the Grand Canyon and you suddenly had to get across that? How would you do it?’ With ladders and so forth. We came up with a theory of what we wanted the action to be. Now, you have to create physics to make that happen. How would it feel feasible? The fact that is true is when the tectonic plates have shifted so much, the world was nothing but seismic activity. The world is bending and shaping and moving and continents fluctuating. We were able to play with the seismic activity to where this monster is not just in the air. The monster is also underneath your feet. It’s in the ground.”

“The scale was always the big challenge because every time you’re thinking, ‘This is going to be big enough.’ In the end, it’s not. The director wants bigger, and then more. You always have to amp the scale of everything. The storm had to be much bigger. The impacts for the forest sequence we had a big setup, and then it was like, ‘Nope, much bigger. The sky has to be completely covered.’”

—Marc Massicotte, Visual Effects Supervisor

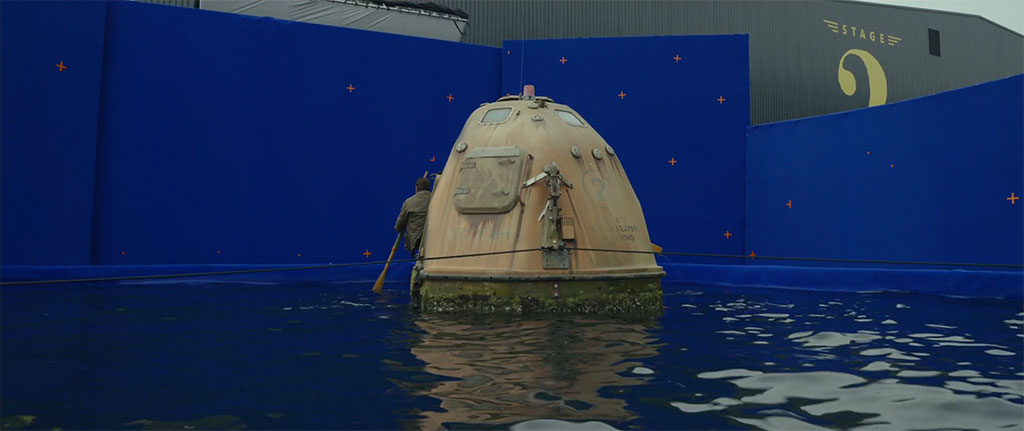

Complex to execute was the fleeing inhabitants of the destroyed bunker attempting to escape from the coast of Greenland. “I would say the sequence that was by far the hardest, because of safety and making sure everybody was good, was shooting everybody storming the lifeboats on the beach,” Waugh reveals. “Because you’re dealing with hundreds of background people who are real people in Iceland. You’re dealing with stunt players. You’re dealing with Marines. You’re dealing with Mother Nature, where the ocean changes constantly. You’re dealing with water that was in the 30s Fahrenheit. You’re dealing with so many different elements of keeping people safe who are getting wet, and getting them into warm tents. How do you have crew be safe out there? How can you shoot physically with cameras? It was a major undertaking. We shot on the same black sand beach at Sandvik in Iceland where Flags of Our Fathers was shot. That was Iwo Jima Beach, and it was interesting to be there and see that. I’m proud to say everybody walked away from that with no injuries. We took care of everybody.”

Despite the importance of scope, everything rides on the audience empathizing with the characters. “It’s how to create intimacy where you feel like you’re attached to these characters, going across these ladders and across these peninsulas and facing sheer death,” Waugh notes. “Then, create the scope of a vast canyon, the depth of it and the sheer magnitude of everything. I always try to shoot movies from the inside out versus the outside in, which means that you’re creating as much of an intimate portrayal with your characters. Then you also have to able to open up the lens to where you see the world around them versus a lot of movies that are shot from the outside in. They give you the sense of scope, but don’t give you the emotion of the character. My job is emotion first, and then to build the scope around it. It’s challenging sometimes.” Overall, Greenland 2: Migration went well. “We had a solid team,” Massicotte notes. “Besides the technical challenge of scaling, there wasn’t a whole lot of challenges in regards to asset sharing. We didn’t have that. We didn’t have any issues with our vendors. Everyone was fantastic.” There are a couple of highlights. “Definitely the opening of the film and the crossing of the English Channel. But the whole film has so many visuals that are amazing. It’s hard to pick one or two. I’d say, just go see it and you’ll be along for a ride. It’s a really good road film. You’re constantly assaulted with visuals of what that world is or has become. It’s stunning.”