By TREVOR HOGG

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of FX.

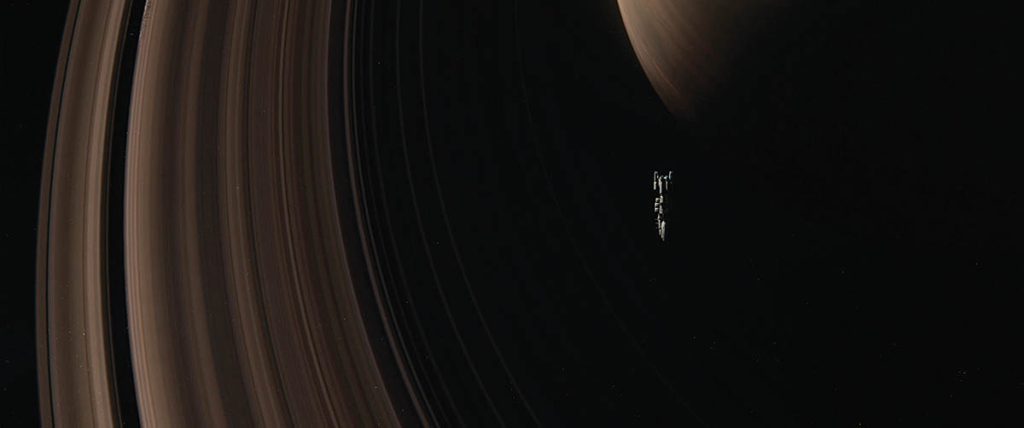

Novelist-turned-filmmaker Noah Hawley has a habit of putting his own off-kilter twist on franchise building, whether it be psychic powers being mistaken for mental illness in the X-Men-connected Legion, honoring the bloody and sardonic sensibilities of the Coen brothers in Fargo, or combining the corporate-greed-running-scientifically-amok theme with the race to commercialize immortality in Alien: Earth. All three of the television productions found a home on FX with the third one set two years before Ridley Scott’s Alien. The show consists of eight episodes revolving around a terminally ill child as she has her consciousness transferred to a synthetic adult body and then attempts to assist her older brother finding survivors from a crashed research spaceship containing five invasive and predatory alien specimens that break free and wreak havoc on Earth.

“The remarkable thing, after seven Alien movies, is how little mythology there actually is,” notes Hawley, who serves as Creator, Showrunner, Executive Producer, Writer and Director. “I’m basically working off the first two films as my template. We know there’s a company called Weyland-Yutani, but what is the geopolitical order on Earth? The luxury for me coming in at this later date is I got to create out of whole cloth. There are five corporations fighting to see who will be the monopoly left at the end. In choosing to explore the Prodigy Corporation and the idea of the Boy Genius, the Peter Pan mythology of the Lost Boys and human hybrids allowed me to take Weyland-Yutani, which is everything to the films, and make it a component of the TV franchise. In the same way, by introducing these new creatures, I’m able to take the Xenomorph, which is everything in the films, and make it a fan-favorite element in the show. My job is to recreate the same feelings you get from the first two films, but by telling a totally different story. One of those critical feelings was for the first time discovering the life cycle of this creature, which expands the horror.”

There always had to be something real in the frame. “I’m not attracted to a pure greenscreen environment,” Hawley states. “There are some shots of ships coming in to land in a city that might be an entirely CG shot, and those can work well. But if you have a green box, I find it tough, and so do the actors, to get into that head space. We had a performer in a Xenomorph suit. For these other creatures, we did not have animatronic versions, but had realistic props made so at least the actor can see what it is they’re dealing with. I also think about the length of the shot. If I’ve got a suit performer in a Xenomorph costume with a tail on a fishing line for a half a second shot, I can buy that. If it’s a stunt in which the tail is going to throw the performer off balance, we remove the tail and do it as CG.” Hawley sought out some visual effects advice. “I ended up calling Denis Villeneuve while I was making the show, and I told him that every other visual reference I have on my wall was one of his movies. He is so good in Arrival or Dune or Blade Runner 2049 at showing you how big something is. It’s actually very hard. I wanted the spaceship crash to feel like a disaster that is beyond human scale.”

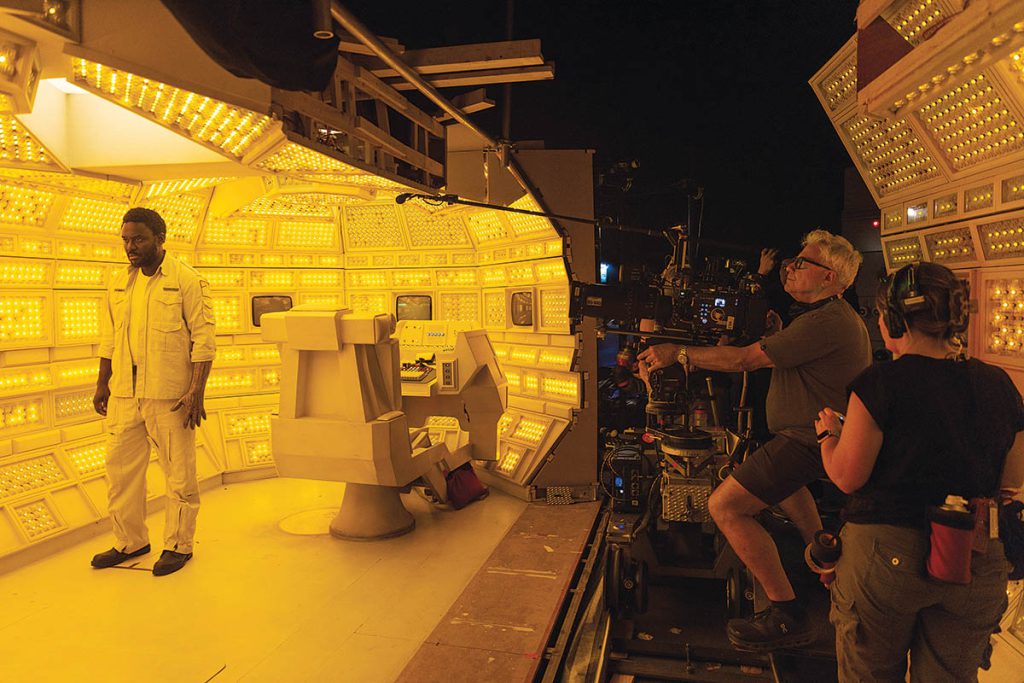

Driving the visual aesthetic was Alien and Aliens. “What I liked about those two movies was that they were at a time where computer design wasn’t used for much of the design drawings, so it was more like the manual version,” remarks Production Designer Andy Nicholson. “But more than that, if you lived in 1979, that was your vision of the future. A lot of the shapes and elements from European furniture and car designs in the 1970s to the early 1980s were in the prop dressing. The Nostromo in Alien had such a solid ship design that was very much its own. It wasn’t like Star Wars or 2001: A Space Odyssey. The Weyland-Yutani ship in our show, the USCSS Maginot, has similar crew quarters, canteens, cryo chambers and bridge because people move between ships, and you have to know where everything is.” Shooting took place in Thailand at three different studios and on 16 to 21 stages. Nicholson adds, “The crew quarter corridors were white and the engineering and flight corridors were darker. We had them set out in the same stage so you could transition and shoot on the same day between places.”

“The creatures were well in advance in terms of what they looked like before we designed and built sets,” Nicholson remarks. “Some of the spaces they appeared in had to be augmented to work with them, but that was more to do with the container vessels. The Xenomorph eggs that get carried into the ship were so big that they dictated the size of a couple of the doors on the sets.” The art department concepted Prodigy “Neverland” Research Island, which is located in New Siam. “We did a two-kilometer by two-kilometer section of Prodigy City in Unreal Engine based around the location we were shooting the crash site. We handed over to visual effects a many-gigabyte package of the city with a kit bash of parts so that you could expand that building type out as far as possible from wherever we needed to.” Elevating the fear factor in the sci-fi franchise is a particular architectural design element. “They’re in this ship with vents everywhere, and who knows how big this alien is? Where’s it going? It doesn’t feel like you shut the door and can be safe. It’s not even safe when Ripley gets into the shuttle at the end of Alien. We wanted to keep that fear going through this, and that’s the reason why there are vents in all the rooms in Neverland, even in the operating theatre.”

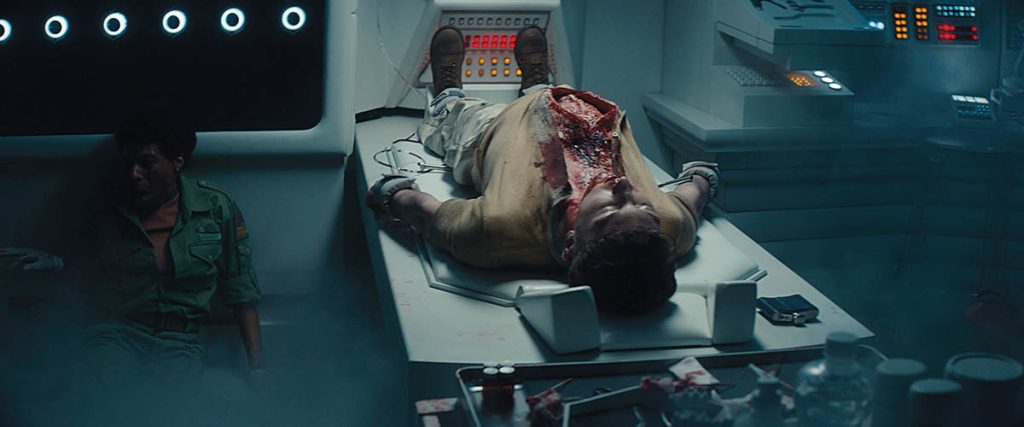

The static, animatronic and puppet renditions of Xenomorph eggs were significant prop to construct. “We decided to do a few different versions, and gave them various textures to see which one looked close enough to the original,” explains Sarinnaree “Honey” Khamaiumcharean, Creature & Prosthetic Supervisor. “We had more than 30 eggs on standby that were made from soft silicone and had a clear, slimy liquid put on top. A full version was made where everything moved in a creepy way. When the egg opens you see the placenta of a Facehugger. It was our masterpiece! We also had fun creating a super-detailed two-centimeter Chestburster that was put into a tube placed inside of a lung. It’s going to be the new iconic scene!” Making an alien creature that has never been seen before appear realistic enough to be onscreen was a significant task for the crew in Thailand. “We had about 10 sizes of Ticks. The big Tick could suck all of your blood out. I called my friend, who is a doctor, and asked, ‘How many liters of blood do humans have?’ It’s four to five liters depending on your size. We put in a sac that had four to five liters of blood to see how it was going to look.” Complicating matters was the climate. Khamaiumcharean notes, “We live in a country that is quite humid and hot, so the bigger challenge was for us to find the material that could be kept outside for a long period of time. It’s difficult to keep things in the fridge all the time. Also, we had to continually remake synthetic blood because every two weeks it would be gone!”

Whether for a television or feature production, the quality and standards for prosthetic makeup are no different. “The problems you come across are exactly the same,” notes Steve Painter, Lead Prosthetic Supervisor & Designer. “I will prepare two or three takes of prosthetics as backups. The fake dead bodies were sourced offsite in the U.K. because there was just no way with the number of people I had in Thailand and the local materials. Sometimes the paint was still wet when we were taking them onto set. It was close.” One has to be able to adapt to the on-set conditions. “If you cool hair in the humidity in Thailand, it straightens by itself, so you have to hairspray the heck out of it to keep the hair where you want it.” An important relationship was had with the visual effects team. “If Jeff Okun [VES, Onset VFX Supervisor] needed something from me, I was happy to give him whatever he needed to make his life easier. From my point of view, there are certain things we can’t do physically, and that’s where Jeff came in. We became good friends over the course of the shoots and production.”

“Basically, all the killings were down to us, and it was great fun to try to work out how,” Painter laughs. “There’s a character, Bergerfeld [Dean Alexandrou], who literally gets his face ripped off by the Xenomorph,” Painter states. “We had him crawling away wearing green leotards because he supposed to have no legs. A stuntman representing Bergerfeld was all wired up, and the Xenomorph has his head in its mouth, lifts him up like a ragdoll, shakes him around and then throws him. It was incredible when we watched it being shot. David Rysdahl’s death was a huge scene for us. I got onboard with one of the Jurassic Park and Star Wars animatronics guys who I’ve known for years, and we designed what had to happen. Noah sent me the Chestburster scene of John Hurt in Alien, but what he did not tell me was that it would be on a beach in Krabi. We did a mock-up of part of the beach in Bangkok and had a raised platform, so all the puppeteers were underneath. Where we tried to improve from the original Chestburster scene is you never see John Hurt’s legs. I wanted to see the whole body, so I devised a puppetry system where we could puppeteer David’s fake leg. It was the legs moving and twitching that sold it, that this is not a man appearing through a hole in the table for his head and arms. It looked amazing, and I even got to hit the lens with a blood spurt!”

“I’ve been fortunate enough to work on Star Wars, the recut of Blade Runner and now Alien, so I’m living my kid’s dream of sci-fi,” states VFX Supervisor Jonathan Rothbart. “The mantra of mine on this show is anytime we start seeing visual effects that feel modern, I always tried to push them back to the look and feel of 1979.” The digital augmentation was impacted by the choice to shoot with anamorphic lenses. Rothbart observes, “We spent a lot of time mapping out and focusing on what those anamorphic lenses are doing and how they affect all the images because each one has its own little texture and look. We did a lot of softening of things to get it to play in the plate, and then we also have the chromatic aberration where you start seeing the different colors split on the edge of the frames. And, of course, flares and grain level, which is not the lens but us trying to emulate the right kind of film stock.”

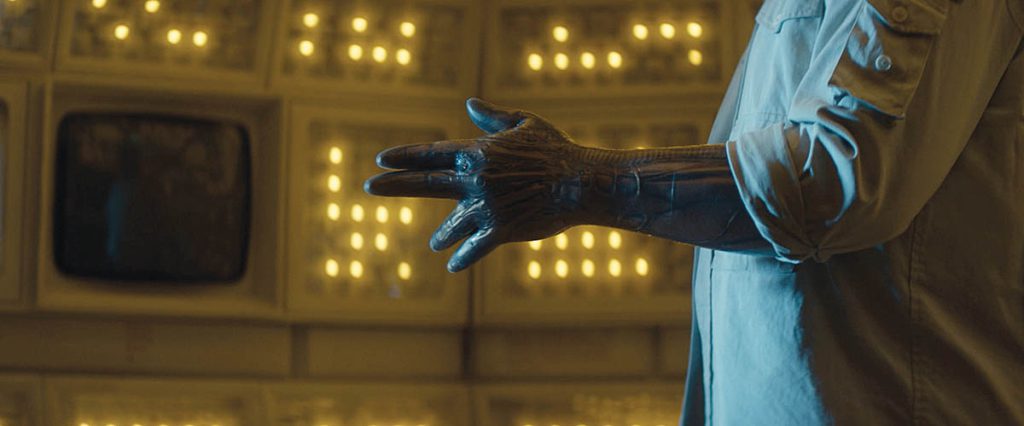

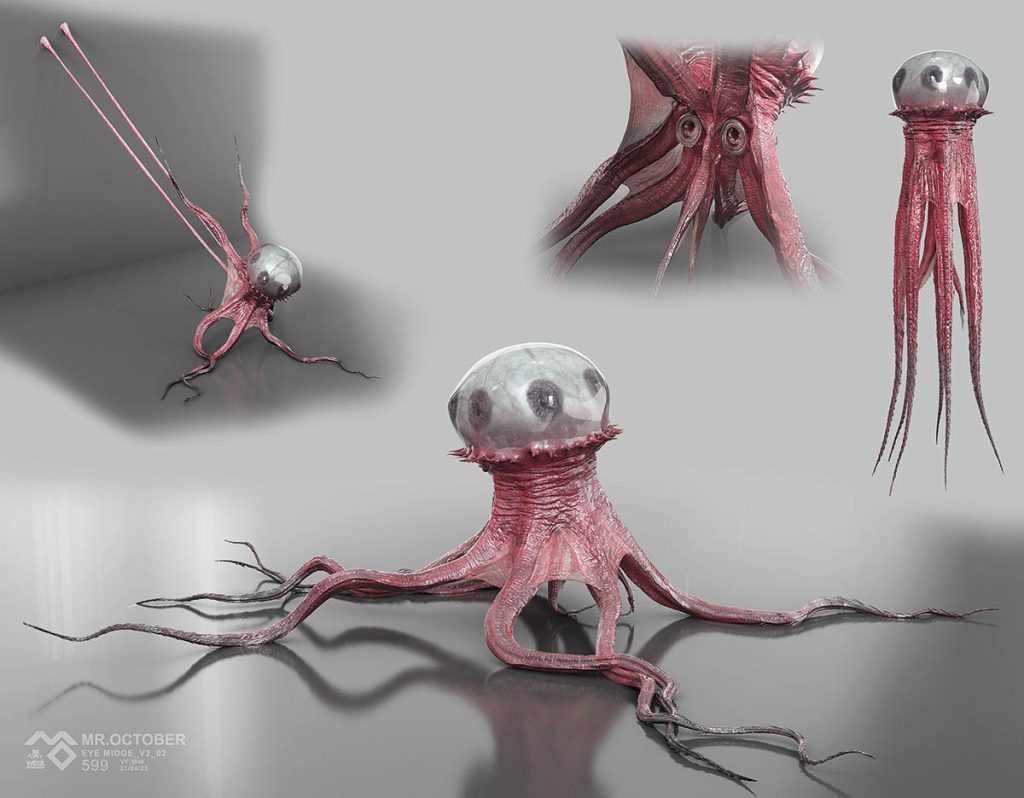

Along with the Tick, other new creatures featured in the 2,000 visual effects shots are the Eye Midge, Orchid and Fly. “Anybody who asked me, ‘What’s your job like?’ I answer, ‘It’s the best job in the world!’” Rothbart laughs. “I get to make spaceships and monsters. We’ve got some great facilities. Our primary vendor was Untold Studios, which did the Eye Midge and Xenomorph. Pixomondo came on later as well. Zoic Studios handled the Tick and the Orchid. UPP did the majority of the space work, and Fin Design + Effects did Morrow’s CG hand. The two hardest creatures were certainly the Eye Midge and the Tick. I love the Eye Midge most of all because we’ve been able to put so much character into its little moments. But the Eye Midge is also this evil, vicious creature that is intelligent and takes over whatever vessel it puts itself into it. At first, the animators were giving me this sheep with an Eye Midge, but I said to them, ‘It has to be an Eye Midge trying to control a sheep so it moves quirky.’ As for the Tick, any subtle changes in lighting really affected the way the character looked. It was a lot of work to get the Tick to feel right, and it’s in so many different lighting scenarios. Then there’s the difference between when the Tick is filled and not filled with blood. That was definitely a process to figure out.”

Prodigy City was a major environment build. “We had gotten some concept art from the art department, and Noah was interested in telling the substory of what he called the ‘plus versus minus’ of society,” Rothbart states. “The idea that the wealthier lived above ground and the poor people live in all these dwellings below ground. We tried to come up with a structure that would both be believable and make sense to that concept. We added these levels of the city. Most of the events in this particular season take place in the upper level of that city. It’s a cool concept that I’m hoping Noah will investigate further next season.” Plate photography was always the starting point. “We would strip out a lot of the buildings, then rebuild our buildings on top of that, as well as the lower area underneath it so we felt more of that futuristic city. We’ve got some really huge shots like the big ‘oner’ when they go to the crash site, which was insanely difficult with so many layers and so much going on.” Sparks are a prominent atmospheric in the crash site. Rothbart notes, “We took what was there and tried to minimize the sparks in a lot of places and then rebuild them back with our own sparks so we could be more specific with the art direction.”

“I ended up calling Denis Villeneuve while I was making the show, and I told him that every other visual reference I have on my wall was one of his movies. He is so good in Arrival or Dune or Blade Runner 2049 at showing you how big something is. It’s actually very hard. I wanted the spaceship crash to feel like a disaster that is beyond human scale.”

—Noah Hawley, Creator, Showrunner, Executive Producer, Writer, Director

One of the more stunning reveals occurs when Wendy (Sydney Chandler) displays the superhuman strength of her new synthetic adult body by jumping off of a cliff, landing safely on the beach and sprinting at a high speed back to the Neverland research complex. “We had a cliff that they had photographed, but it wouldn’t work with the distance and scale,” Rothbart reveals. “We ended up, making that a fully CG shot for the jump down, then we have a takeover from when she stands up and does her initial jump. Those shots are always hard because people have a side-by-side comparison of live-action to the CG.” A subtle and extensive effect was the CG hand belonging to Morrow (Babou Ceesay). Rothbart explains, “That was a complicated asset because you can see through into the internals, but you also have the external. We had to make sure that the captured light hits both inside and outside and plays off each other.” The visual effects will not disappoint fans of Alien and Aliens. “All of our facilities did great work. It’s been a joy for me in the sense that you know the cool things you can do with the shot as opposed to how we get to fix it. That is the best place to be if you’re doing this job.”