By Trevor Hogg

By Trevor Hogg

Images courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Just as Martin Scorsese is closely associated with Robert De Niro, Ryan Coogler has formed a strong creative partnership with Michael B. Jordan. The latter cinematic combo has upped the ante with Sinners as Jordan plays twin brothers returning to their hometown with hopes of leaving behind their troubled lives, but instead encounter an even greater danger.

“I wanted Sinners to be able to be a film without vampires,” states Production Designer Hannah Beachler. “It was more about paying homage to a Mississippi when cotton was king, everybody was on plantations and sharecropping wasn’t that different from slavery.” Impacting the set design was the vertical nature of the IMAX format. “Ryan told me to treat as if it’s normal, but then I didn’t! I knew you were going to see higher, so we had to pay attention to ceilings. There was one part in the church where we had these beams that were a design language throughout the film, which was a cross-X section. I talked to Autumn Durald Arkapaw [Cinematographer] about it, and she had her guys in Los Angeles do some measurements for me so I could decide, depending on where the camera was placed, how much we were going to see.” Lighting was a fun challenge. Beachler notes, “The 1930s is a mix of candlelight and electricity, depending on where you are. Even inside the sawmill, I had a blast creating ways for Autumn to create and mold light, and then not tell her about it! It was magical to watch her find it and see what she would do with it.”

“I’m known for calling Sinners a project that is bookending technologies. We are simultaneously looking back at the beginnings of the moving picture with using large-format film while also utilizing the latest and cutting edge of ML technologies. All for the sake of successful storytelling without letting technology get in the way.”

—Guido Wolter, VFX Supervisor, Rising Sun Pictures

A major lesson was learned while making the Black Panther franchise. “When Ryan and I worked with Marvel Studios, we learned how important visual effects are as a storytelling device,” states Editor Michael P. Shawver. “Before that, we thought of them as being the bells and whistles.” Fireflies were inserted digitally when Cornbread (Omar Benson Miller) relieves himself by a tree outside the juke joint. “Sometimes you don’t want to throw things off towards the end with a new idea, but we had such an open, organic collaboration with the visual effects team. As a kid in the Northeast, fireflies were a big part of my summer, and I asked Michael Ralla [VFX Supervisor] and James Alexander [VFX Producer], ‘Can we do fireflies?’ We talked about how fast the fireflies would light because at first it appeared as if they were blinking rather than being slow and rhythmic. Then it evolved into having vampire eyes open behind Cornbread, which added an extra element of danger, threat and [raised the] stakes, plus the coolness of the fireflies made it visually interesting.” Shawver adds, “Thanks to visual effects and the childlike enthusiasm of Michael and James for anytime a new idea came up, we had a sandbox to play in.”

“One thing I say all the time when working with visual effects is, ‘We’re not going to make shit up,’” notes Cinematographer Arkapaw. “That statement came out of a conversation I had with Michael Ralla on Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, asking him, ‘Why does visual effects oftentimes make things up?’ I take that seriously on set. I do everything I can to help the visual effects team capture the assets they need so the shot is better in post and not built from scratch.” Footage was primarily captured with Panavision System 65 Studio, Panavision System 65 High Speed, IMAX MSM and MKIV film cameras. “We often used the IMAX 15 perf format for heightened emotional moments and action sequences, and System 65 as our main storytelling workhorse.” The main lenses were the Panavision Ultra Panatar anamorphics with the System 65 cameras and the Panavision IMAX lenses for IMAX, which only have 50mm and 80mm. “I asked Dan Sasaki at Panavision to make us an 80mm IMAX Petzval lens because I knew Ryan would love it and we’d find a special sequence to utilize it. The lens has a nostalgic softness and dreamlike quality that helped shape the emotional texture in some of our supernatural scenes.”

There was talk about having 180 visual effects shots, but the workload rose to a total of 1,013 for Storm Studios, Rising Sun Pictures, ILM, Base FX, Light VFX, Outpost VFX, TFX, Baraboom! Studios and an in-house team of six artists. The digital augmentation ranged from a last-minute alteration to a gold ring, Michael Jordan passing a cigarette to himself as a twin, a CG train and vultures, a burning roof, expansive cotton fields, turning present-day Louisiana into 1930s Mississippi and glowing vampire eyes. A new approach was developed to achieve the twinning effect. “We thought of any possible way to put something on Michael and allow him to redeliver the performance in the same space, location and lighting conditions right after Ryan is happy with his take,” explains VFX Supervisor Ralla. “That’s how we came up with the Halo rig. The ring is made out of carbon fiber, so it’s surprisingly light, and the fact that it’s shoulder-worn allows for the weight to be distributed in a way that it didn’t make a big difference to Michael. The 12 cameras were positioned all around his head and had their firmware modified so we could shoot at LOG [log or logarithmic profile or shooting profile].”

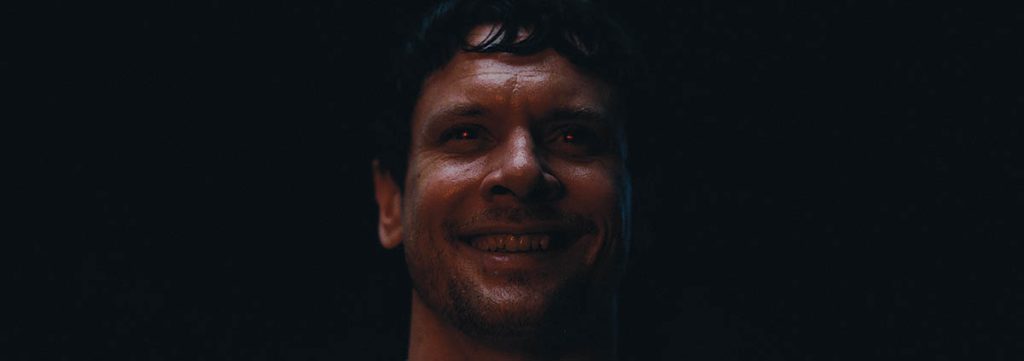

Unlike the traditional two little holes in the neck, Coogler wanted the vampire bites to be massive wounds. “I started studying dog and shark bites to see how the flesh moves and what the bleeding looks like,” remarks Special Effects Makeup Designer Mike Fontaine, who also had to show the adverse effect that sunlight has on the skin of vampires. “When Remmick initially shows up, his body is covered with burns, which were not meant to appear fantastical. I found these amazing photos on medical websites of second and third-degree burns and came to the conclusion that nothing was going to look as real as them. We printed those photos on temporary tattoo paper, stuck them to the body and peeled them off.” There was a specific visual aesthetic for the vampire eyes. “Ryan referenced this effect called tapetum lucidum, which is the reflective quality that you’ll see in the eyes of nocturnal animals. I reached out to this amazing contact lens artist named Cristina Patterson and discovered she had been secretly developing a contact lens that does this effect. These practical contact lenses were able to not just have a paint design but to reflect light in the actor’s eyes.” There were situations where the contact lenses could not be used because of cost, logistical or safety reasons. Fontaine reveals, “This is where the visual effects team came in. They were able to scan and photograph the contact lenses to replicate them digitally. The end result is practical and visual effects working together.”

The surreal montage where musicians from different eras appear in the same room together was more about having a surreal vibe than abstract imagery. “It was all done on set,” states Espen Nordahl, VFX Supervisor and Head of VFX at Storm Studios. “They could have shot this as a ‘oner,’ but it’s on IMAX film, so you’re limited by the physical roll of film. I believe this is the longest IMAX shot ever because it’s using five rolls of film and is around 4,500 frames. Autumn [Arkapaw] and Michael Ralla had planned out the stitches ahead of time.” One of the most difficult twinning shots to execute was the passing of a cigarette between Smoke and Stack. Nordahl remarks, “Split screens are not rocket science, but [coordinating] the interactions requires a lot of work. We did a test in pre-production where that scene was similarly shot on the lot. They had to do so many takes that the sun changed angle, which meant relighting hats and replacing shoulders, or we could use the takes that were closer in time but not rehearsed as well. It becomes a branching thing where every problem we fix has the potential of causing another thing that needs to be tuned because now that looks uncanny. It’s old-school comping, painting, warping and retiming. The hands would never be at the same angle, so we had to recreate a lot of hands and fingers.”

Digitally recreating 65mm film grain and lens aberrations were important to achieve seamless integration. “Ryan and Autumn were keen on making sure that the CG looked like something that’s been photographed on that film format through those lenses,” notes Nick Marshall, Visual Effects Supervisor at ILM. “We received some good lens grids from the production, and then set about making sure we could mimic every little quality of the diffraction spikes, the way the bokeh forms, chromatic aberrations, and near and far defocus.” ILM was responsible for the train station where the train was completely CG. Marshall explains, “Special effects took a steam smoke machine and ran it on a dolly down a track built next to the practical rail tracks, which were there on location. We didn’t want to go full-CG crowd for the large parts of the shots, so having that practical steam interacting with the crowd was a great way to give us something to blend into. When we designed all our train station environment extensions, we slightly repositioned our train tracks to match up with that dolly track they’d built on the location so we could have our train closer to the platform, but running down the same position as the dolly. We carefully integrated some additional steam simulations.”

Light VFX was given the responsibility of producing the ominous vultures that foreshadow the arrival of the vampires. “One of the challenges we had was having birds going from standing on the ground then flying off, and vice versa, in the same shot,” states Antoine Moulineau, Founder, VFX Supervisor & Creative Director at Light VFX. “On a lot of shows, we usually have two assets, one for when they’re walking and another for flying. But on Sinners we couldn’t do that. We had to do it the hard way, which means folding everything correctly, having the right position of each feather, and then, with Houdini, do some cloth simulations on the feathers to make them bend and collide as they should. It was a purely physical thing. It was all edited by hand. We didn’t take any shortcuts. We had real footage of vultures walking around. As we were building our CG asset, it was placed next to the real vultures until we reached a point where no one could tell which one was fake.”

Captured for real was the car shootout at the end. “We took the same car from Bonnie and Clyde: Dead and Alive [2013], which had 118 squibs, and used that for R&D to figure out what the bullet holes would look like and to rehearse the camera moves,” remarks Special Effects Coordinator Donnie Dean. “We did 10% of the bullet hits to start getting the camera moves down and gradually ramped up until we had over 80 squibs on the car going through it on each side. You had it so that the squibs move around the car with the camera because the camera can’t see the entrance and exit [of the bullet hits] at the same time; therefore, you had to space them out but not make it look weird.” Fire has a prominent presence. Dean remarks, “We now have access to materials that are more fire resistant than you might have had 10 or 15 years ago. You see the barn door go up in the movie, and we could build that in a way where you can burn it and turn it off and it’s not marred. When you see the ceiling burn away, that’s a different story. That took three months to figure out. We tried different materials because there is a certain amount of time [30 to 45 seconds] you have for that roof to burn away. The fire tornado [caused by the death of Remmick] was practical, and that also took us three months. It was a combination of a mechanical situation with propane adaptors. There were fireballs spinning around that create the swirl and a big metal turbine in the middle of it all. We fed that with big vacuums used for [cleaning] parking lots. We plumbed that in to push the air into the big turbine and then plumbed it with massive inlets of propane. If you shove enough propane in there it will still burn. We went through a $1,000 worth of propane for one shot. The fire tornado went 60 feet high and touched the ceiling of the studio!”

With the proliferation of digital cameras, whole generations of digital artists have never worked with celluloid, in particular 65mm. “I gave 90-minute lens seminars on Zoom, and Nick, Espen and Guido had to train their compositors how to work with film because they had never touched scanned celluloid,” Ralla states. “People were going, ‘What is dust-busting? Where are these scratches coming from? Why does one frame pop?’ We had to come back to what was filmed and apply that to all of the CG stuff. It gets tricky because this film has 1,013 shots, which is more than 50% of the runtime.” Dealing with celluloid is not terribly complicated. “It requires an understanding,” Nordahl notes. “We need to get rid of the unwanted artifacts like hairs, keep the grain and halation, but not the gate weave [which is a creative choice]. It was like a re-education of a lost art, and the resolution of those IMAX plates were ridiculous!”