By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Universal Pictures.

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Universal Pictures.

Continuing the story of how the Wicked Witch of the West came to be in the Land of Oz is Wicked: For Good under the direction of Jon M. Chu and starring Cynthia Erivo, Ariana Grande, Jeff Goldblum, Michelle Yeoh, Peter Dinklage, Jonathan Bailey and Ethan Slater. “There’s a lot of discovery and collaboration between the departments and between Jon and us,” remarks Pablo Helman, Visual Effects Supervisor. “We had an attitude and environment where we could offer things to Jon, he made choices, and the movie became what it was always meant to be for him.”

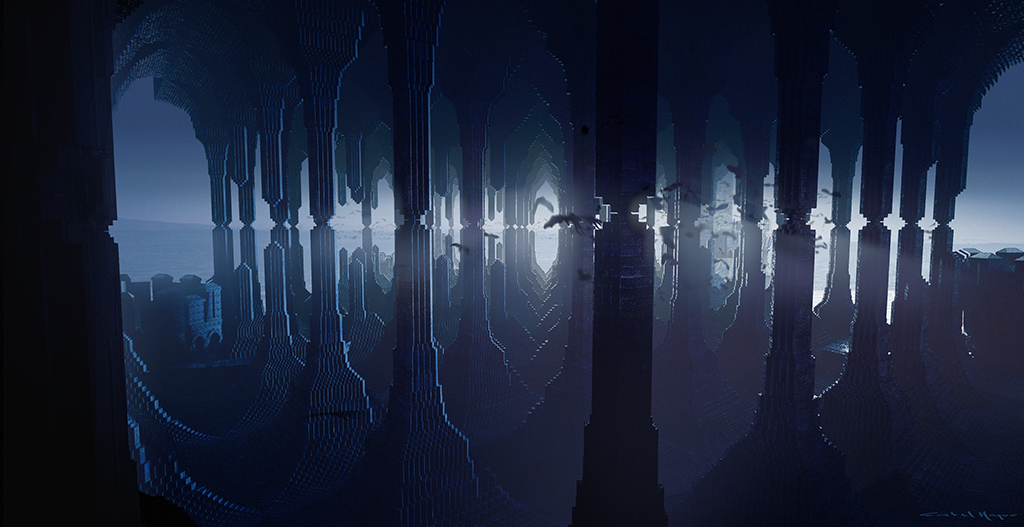

ILM and Framestore were the main vendors along with Rising Sun Pictures, Outpost VFX, OPSIS, BOT VFX, FOY and an in-house team contributing more than 1,800 visual effects shots. “You learn a lot from the first film in terms of what makes a character be the character that we want to see in the movie,” Helman states. “There’s a lot of development in terms of hard surface assets. That’s to do with creating a city and being able to see all of the materials shine in the light through wide and moving shots. There were changes that had to do with avoiding pixelation or moiré patterns in tight spaces and high-definition work.”

A broom chase through a forest harkens back to an iconic action sequence from Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi. “It’s different because we shot the trees in England, which are different from the redwoods in California,” Helman remarks. “The skies around London were cloudy, so we didn’t get a sense of light direction. One of the things I’m always looking for is light direction because it gives everybody a sense of geography. Once you have the sun in there, you can put it wherever you want and there’s always something present that tells you exactly where you are. Having said that, we did shoot a bunch of a plates, but we had to replace a lot of it, because we had to put the curly trees in it, and Oz-ify it. There’s a lot of atmospherics that were in there when we shot, meaning that we put some fog in there that gives us a sense of depth. Then we put a bunch of monkeys and an Elphaba [stand-in] through it. We played a lot with leaves and smoke and a bunch of other things that had to do with the content of the sequence.”

“If you look at the way the bubble expires, there’s a lot of mist that comes with that, and with that comes an opportunity to do a rainbow.”

—Pablo Helman, Visual Effects Supervisor

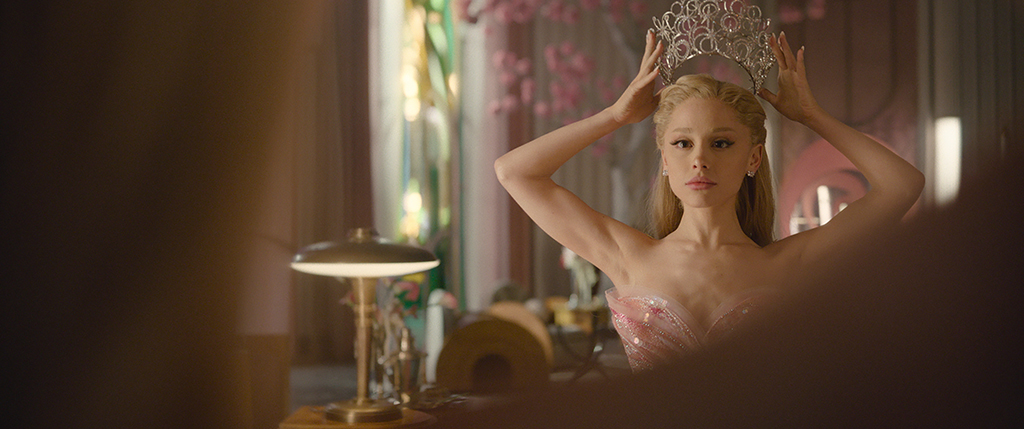

Pink bubbles are associated with Glinda. “There was a lot of exploring,” Helman explains. “When you think about a bubble, you ask, what is it made of? That’s the first question that comes up. Is it soapy or oily? Does it move a lot? Does it fluctuate? How much can you see through and what are the reflections doing? The reflections will tell you a lot about the material. If the reflections are sharp or pinky or sharp highlights, that tells you one thing about the material. We went less than shiny. We paled it up, so that actually spreads the materials around and causes the highlights not to be as sharp. Then there were the edges. How sharp are those edges and how sharp do they need to be? There’s a lot of talk about movement and how it starts and ends. If you look at the way the bubble expires, there’s a lot of mist that comes with that, and with that comes an opportunity to do a rainbow.”

Assembling musical set pieces is made tricky because communication is done through technology rather than in person. “They hear what you’re saying, but might hear it a few frames later,” Helman observes. “We would ‘beat’ things, and Jon would mark different things and say, ‘Do this by this speed.’ Or he would sing or clap it. For example, the writing in the cloud that ILM did was music-oriented in terms of getting to this cloud by this beat. Because we work with editorial, and Ed Marsh [Senior Visual Effects Editor] was in the room with his Avid, we would mark all that stuff with colors and things like that. Music adds a mathematical entity in there for the work that you do. But it also adds emotion when there are certain intervals, like sixes, fifths and crescendos. Story and music is the same thing as film. It has a beginning, middle and end. It has texture, color and tells a story.”

“Music adds a mathematical entity in there for the work that you do. But it also adds emotion when there are certain intervals, like sixes, fifths and crescendos. Story and music is the same thing as film. It has a beginning, middle and end. It has texture, color and tells a story.”

—Pablo Helman, Visual Effects Supervisor

Complex to execute was the new song, “Girl in a Bubble,” which made use of mirror reflections as Glinda literally and figuratively questions herself. “We did previs for three weeks for all of the things that production design had to provide for walls,’ Helman reveals. “Because the camera starts in one place and goes through it – so the wall is out – it comes around, and as it comes around and sees itself, it does a complete circle, and the wall comes back in. Not only that, the reflection that is in that wall had to be put in in CG. That’s another pass which needs to be done. All of that was done without motion control. It was just faith! There were a lot of other things we used like Technocranes that have to go to places that had production design parts of walls that we had to take out so the crane could come in, but then you would see it. We had to put the wall back in CG, like the parapet behind Glinda right before she goes into the closet. All of that is CG as well as the ceiling because it was a two-story set, so it went all of the way to 25 feet [high]. When you are on a wide lens, you’re going to take a look at everything that is in there.”

As things begin to fissure, the characters change. “Chistery starts with the wizard and ends up on the witch’s side,” Helman states. “The idea is that you go through that arc – and that has to do not only with behavior but also with wardrobe and ruggedness of their appearances. Dulcibear has been through exile, so it’s not the same Dulcibear that is the nanny who has been fed and dressed in a specific way. Now all of her belongings are in her bag, and she’s carrying them around, and she’s rugged, and that also carries in her face for the animation; her performances are going to carry a lot more weight. In terms of Dillamond, we have seen the pride of an animal as a professor, but now we see him in a prison.” Scarecrow becomes an actual scarecrow. “The transformation does not happen in isolation. They occur in relation to the specific environments that these characters are in. If somebody is going to be turned into a scarecrow and that somebody is in a cornfield, then corn is going to be part of that transformation.”

The Cowardly Lion had to be appropriately named. “We took a look at many references of animals in a repentant attitude,” Helman states. “Lots of dogs that have done things and don’t want to get caught and are looking up or not looking. There is the attitude of the eyes and eyebrows. There is also the tail. Grabbing the tail and using it for wiping tears. That was in the original drawings of the book. We took a lot of that. The premise of the whole movie is that the animals are animals, and they talk the same way that a dog says, ‘I love you.’” The famous destroyed farmhouse that brings Dorothy and Toto into the narrative via a tornado was not a newly constructed set. “It was there in the first movie, but we removed the farmhouse in visual effects because, for continuity reasons, we couldn’t see it, but we couldn’t move it because it was already built.”

Journeying to the Land of Oz for Wicked and Wicked: For Good has come to an end. “It’s a sadness that you feel because you work with these people for a long time and now they are moving on,” Helman reflects. “The funny thing in our business is we keep running into each other for 20 years. That’s the way it is. You also need a break between projects because it’s an intense relationship that you have with those people. We shot for 155 days. Usually, a project is about 70 days. There’s a reason for that. On day 71 we turn into pumpkins and go, ‘Why are you looking at me like that? Get your elbow out of there.’ But we knew that we had to work with each other for 155 days. We did our job in terms of telling a specific story and feel very satisfied.”