By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Disney+.

By TREVOR HOGG

Images courtesy of Disney+.

Originally a series of children horror books written by R.L. Stine and subsequently adapted as an episodic anthology television series, Goosebumps was resurrected by Rob Letterman and Nicholas Stoller as a serialized anthology for Disney+ and Hulu with the second season titled The Vanishing consisting of eight episodes. The story revolves around an abandoned military bunker situated near Gravesend, Brooklyn where four teenagers disappeared three decades ago in 1994 and the unleashing of an extraterrestrial substance with the ability to shape-shift. While Hilary Winston handles showrunner duties, Lawren Bancroft-Wilson is once again responsible for digitally enhancing the scares. “Before I came to the Goosebumps series, as a whole I would have thought accessible family-friendly movies like Amblin [Entertainment], which I grew up watching,” notes Bancroft-Wilson, Senior Visual Effects Supervisor. “But it was when Rob Letterman started to explain Goosebumps’ magical formula, which is you had to give a lightness and humor in those dark moments, that made it accessible. Like Amblin, Goosebumps tries to make scares in a world that we could possibly live in. It’s not elves and dwarves.”

Just over 1,000 visual shots were produced for the eight episodes. “We knew the creature work that had to be done, so Wētā FX came on as our main vendor,” Bancroft-Wilson explains. “Pixomondo did the car and eyeball. Distillery VFX helped with the lower lab and alien ship stuff. Suburbs VFX took over every other curveball. It was crazy. There were only four vendors.” Improvisation was part of the creative process. “We’re working with a writing team, Hillary Wintson and Rob Letterman, who come from comedy and are not like, ‘The word is the word. Don’t change anything.’ They’re happy to experience happy accidents, and that’s where you get the fun stuff. Writing it, you would have never known we would have been able to do that. David Schwimmer brought that to it as well. Because he did that, the animators made the animation of the vines slightly different, like little tendrils. We looked at a lot of examples of how they grow in time lapse, and I said, ‘Okay, more playful.’ We looked at how it grows toward light, so you get a personality to it. Once it comes out of his arms, you get an idea that, ‘This is an organic thing.’ However, there are these beats where you go, ‘It’s sentient. It’s not just reacting. It has a plan.’ My hat is off to everyone. That was a tough one to plan. Building the prosthetics, figuring out what we could do on set, and once it went into post we spent a lot of time of just figuring out what made it feel real and not off into fantasy land. David has these great, huge expressions, so we had to do something which helps justify that.”

“We’re working with a writing team, Hillary Wintson and Rob Letterman, who come from comedy and are not like, ‘The word is the word. Don’t change anything.’ They’re happy to experience happy accidents, and that’s where you get the fun stuff. Writing it, you would have never known we would have been able to do that. David Schwimmer brought that to it as well. Because he [added his thoughts], the animators made the animation of the vines slightly different, like little tendrils. We looked at a lot of examples of how they grow in time lapse, and I said, ‘Okay, more playful.’ We looked at how it grows toward light, so you get a personality to it.”

—Lawren Bancroft-Wilson, Visual Effects Supervisor

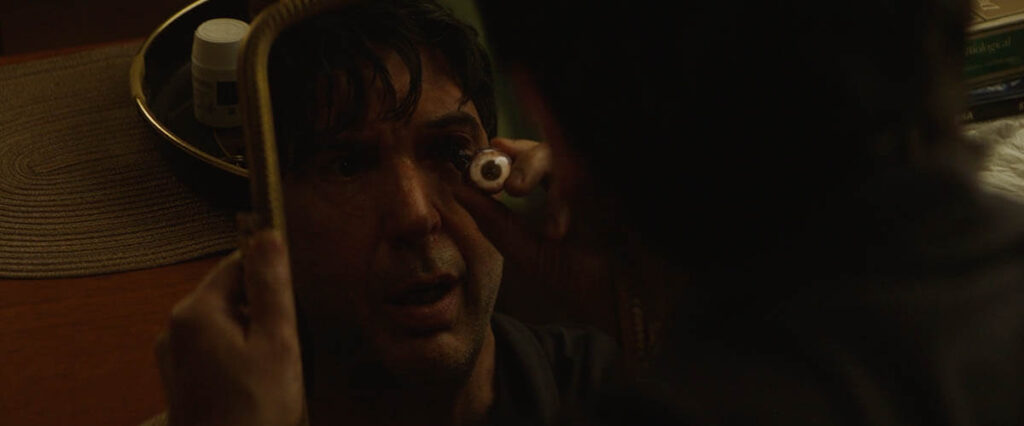

A forceful sneeze results in a dangling eye. “This is part of the job where you end up looking at a lot of stuff you don’t want to see, but it exists,” Bancroft-Wilson observes. “You can see loose eyes out of sockets. That was one where the prosthetic played a large part of it. We got to use the physics of that and little tweaks or adjustments. The dangling eye is mostly real.” The movement of the prosthetic was toned down digitally. “The thing with prosthetics a lot of the time is they can feel a little comical because in our head this is what it would be, and when you see the actual physics play on set with the performance, it is maybe too much. However, there are a lot of scenes we didn’t touch.” A car gets bent out of shape and then fixes itself after an alien substance infiltrates the fuel. “We spent a lot of time figuring out exactly how it dents and crumples up, then have it come out in a way that it felt affected by these sentient things. That it’s not just a car doing bam, bam, like what it would normally do. But there was a pacing to how it goes and for the lights to give character to the car.” There is a logical progression. “The front of hood can’t repair itself before the [rest of the] front [end], so you get that natural cadence or pace of it. But even then, it was making sure that the timing felt like the car was doing it to itself.”

There are shots where the dismembered head of David Schwimmer appears on the basement floor and on a table. “Anytime you have to do a dismembered body part and the actor has to be there, it’s not comfortable for them,” Bancroft-Wilson explains. “We had David propped up on something in the same position but above the floor, figured out the camera angle and everything, and then mashed it down. We are taking his head basically in that same location with all of the same lighting, removing it, then dropping it down to the floor. He still had to be lying on the side there and do everything.” Compositing is essential in making the effect believable. “You’re not putting too much weight on any one party. All of the different departments are coming together and saying, ‘This is what I can do.’ For lighting, we want to make sure to do it right in that location. The compositors are already working from an apples-to-apples range. When they bring the head down and put it on the floor, there’s work to do, such as shadowing and an effects simulation for the neck to make sure that the blood is constantly flowing. We also had a false David’s head that was used for blocking. There wasn’t enough of the secondary black fluid moving, so effects were added to make sure that there was a good movement. Whenever you’re doing any sort of destruction, whether it’s a body or a building, as soon as you break up that surface layer, it’s, ‘What do you see underneath? How many bits and pieces?’ We worked with prosthetics to construct a good cap, and visual effects took over and built on that to add more detail and continual motion.”

“Brooklyn is a character in the show, and we had to make sure it felt like being in real Brooklyn, which meant shooting on real streets. We didn’t have to build environments to put us somewhere, but we did have to mix stuff around for the different time periods.”

—Lawren Bancroft-Wilson, Visual Effects Supervisor

Causing havoc is an alien sentient fuel-like substance. “A lot of that is an oil tackiness-like substance. One of the key things with all of the creatures in the show is that they come from the same thing. It starts off as spores that turn into a black liquid metal that moves around and goes into the car. You see it when the substance affects Trey that it is always wet and has a coating. As the characters melt down, they turn into the black slime that goes back to the fort. We made sure that touchstone and characteristic is across all of the creatures. The final creature is 100% built-up of this ferrofluid, which we looked at to see how it reacts with stuff and how it holds together. It creates an actual bone structure and liquid area, but at the same time still coating it. For the gelatinous feel, we looked at a lot of deep-sea creatures.” Black does not stand out in dark environments. “There were a lot of conversations about how dark we could be and how you read stuff off, because the nice thing is when you see glints of things. For the creatures, we would highlight them with little kick lights so you get that they’re a dark creature in a dark environment, but because of that liquid fluid you get a specular hit. The blob was difficult because of the way the light refracts through it.”

Practical elements assisted with lighting integration. “I don’t know how many different variations of black goo we had, but there were several,” Bancroft-Wilson notes. “We would dress it on people and on set. Mike Myers [Special Effects Supervisor] and his team were always ready with buckets of the black goo. Thomas Yatsko [Cinematographer] knew how to light it to get that nice specular hit and lighting on street in front of the Brewer’s house, to have the big backlight that is coming down, and knowing how we were going to move aliens through the street was a well-choreographed thing. We had tons of iterations on the surface materials of the aliens showing how light would transmit or reflect off. As we looked at the underwater creatures, there is a self-luminous aspect that we worked in.” Principal photography took place in Brooklyn. “Brooklyn is a character in the show, and we had to make sure it felt like being in real Brooklyn, which meant shooting on real streets. We didn’t have to build environments to put us somewhere, but we did have to mix stuff around for the different time periods.” Multiple sets had to be combined into a single location. “You literally have the control room, which is from the big, cool 1960s with big switches and lots of sparks. Then you have a stairway in the middle, and another set that is a bit of floor and a ladder and goes to a slightly lower part. We added the rest of the metal stairs going up, and the metal stairs had to be built as a separate piece to connect the long walk down. There were four sets that needed to be able to have characters move up and down between them, but we were jumping between the sets and stitching them together in visual effects.”

Complicating matters was the found footage. “Growing up in the 1990s,” Bancroft-Wilson remarks, “I was the kid at school who had his Handycam and recorded everything. I pulled from my library from the mid-to-late 1990s to look at what the Sony footage used to look like. We got a bunch of old cameras and recorded on them. We did this whole thing, which was how disconnected does it become if we used these effects as opposed to doing something real and natural? I can only imagine the stress of the executives when Rob said, ‘I want to shoot this on a 1990s camcorder.’ We shot a ton of stuff on an actual old 1990s camcorder. On the visual effects side of it, for the stuff we couldn’t shoot that way, we had to figure out what was needed to get it an exact match back to that. The tests and look development for that went on for a long time. Carlo Monaghan, the other visual effects supervisor on the show, dove deep into that and discovered at what point the lighting blooms out and how it affects the edges. Because we’re a show that shoots anamorphic lenses, we were already sensitive about the textures of lenses in how they look. I had PTSD many times watching our visual effects footage cut right against actual 1990s captured footage, and you go, ‘That better match.’ We do this because we’re all into creative problem-solving, and that was a fun curveball that Rob threw our way!”